NPS/ A. Cassidy The Bascom AffairChief Cochise was leader of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache, local to the Chiricahua Mountains, in the mid-1800s. He was a natural born leader. His father-in-law, Chief Mangas Coloradas, who was chief of the Mimbreno band, helped him foster these skills. Through this connection, Cochise would gain more influence over the Chiricahua Apache.In 1861, the Arivaipa band of Apache (not a part of the Chiricahua) raided the farm of settler John Ward and were seen heading toward the Chiricahua Mountains, known to be Cochise’s territory. The raiders had taken livestock and kidnapped John Ward’s stepson Felix Ward. The young and eager Lieutenant George Bascom was ordered to bring the raiders to justice. Bascom invited Cochise to a meeting near the Butterfield Stage Station on Apache Pass. Cochise agreed to meet him and brought along a few of his family members. In the privacy of his tent, Bascom accused Cochise of the raid. Cochise told him truthfully he had no knowledge of the ordeal, but would help track down those who did. Bascom refused Cochise’s offer and his release until the property was returned. Cochise quickly cut a hole in the tent and escaped. Bascom took Cochise's family members hostage. In the days that followed Cochise ambushed a wagon train and Butterfield stagecoach, taking prisoners of his own. Although both sides wanted to make an agreement, miscommunication and hostilities prevented it. Cochise tried to coordinate an exchange with Bascom, but Bascom refused. Cochise killed his prisoners,and the soldiers killed theirs in retaliation. Among the Apaches killed was Coyuntura, a favorite brother of Cochise. Cochise was devastated and furious.

NPS

Public Domain The Battle of Apache PassOne year later, in 1862, Chief Cochise and Chief Mangas Coloradas assembled the largest war party of the Apache Wars, roughly 200 warriors. With the advent of the Civil War, Union troops were stationed in the area to prevent the Confederacy from gaining the Southwest. On July 15, 1862, about 120 Union soldiers, part of the California Column, were marching east from Tucson. They were tired and thirsty. The soldiers made their way through Apache Pass toward Apache Spring near Fort Bowie. The Apaches probably saw an opportunity to plunder the military wagon train.The Chiricahua attacked the soldiers from the hills above. The Battle of Apache Pass, one of the largest battles in the Apache Wars, ensued. The Chiricahua might have been successful had it not been for two Mountain Howitzer cannons. In reference to the Mountain Howitzers, an Apache warrior stated, “We would’ve won if you hadn’t fired wagons at us.” Bewildered by the destruction, the Chiricahua scattered and retreated. In the aftermath of the battle Mangas Coloradas was badly wounded. His warriors carried him all the way into Mexico where they threatened a doctor into helping him. The first Fort Bowie was built near Apache Pass and Spring to guard the area from future attacks. The Apache WarsThe Apache Wars, though long, were not fought in the manner of most wars. There were very few open battles. Ambushes were common. The Chiricahua did not consider retreat shameful, but a useful tactic. They would usually only engage in open battle if they had greater numbers, the higher ground, or the element of surprise. The Apache Wars lasted 24 years.Mangas ColoradasChief Mangas Coloradas lost much of his will to fight after the Battle at Apache Pass. He was invited into negotiations at Fort McLane in New Mexico where he was killed. The loss of Chief Mangas led Cochise to take up leadership of the Chiricahua. Capturing or defeating Cochise now became the key to U.S. victory. Over a hundred years later, many Chiricahua people remember the Bascom Affair and the death of Mangas Coloradas better than the attack on Pearl Harbor.

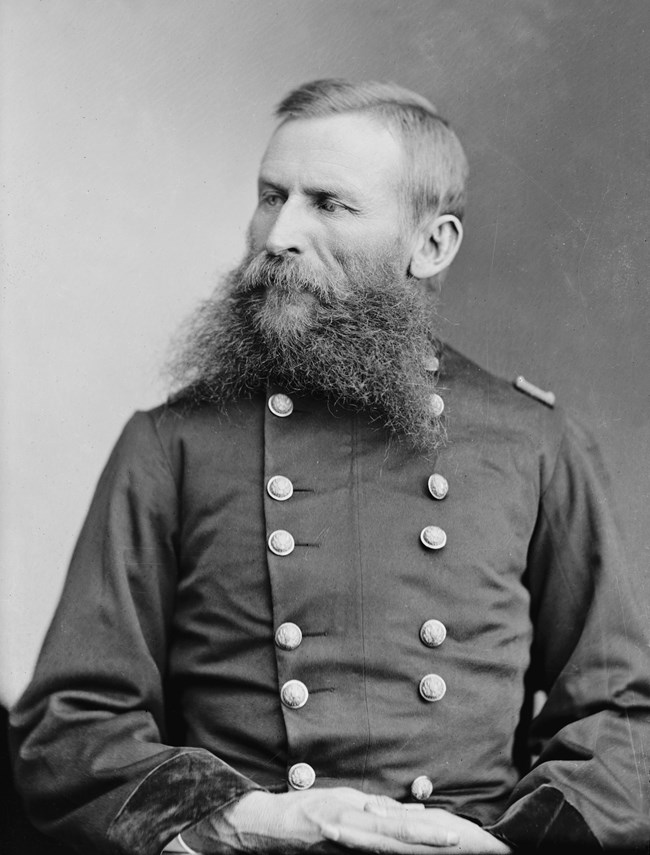

Public Domain/ Library of Congress, Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. Cochise on the RunChief Cochise began to operate primarily from the impregnable mountain rock formation known as Cochise Stronghold in the Dragoon Mountains. Tall rock spires allowed lookouts to see anyone approach from far off. Many hiding spots allowed for easy ambush. The Stronghold was never taken. Cochise still ranged across a huge area--from Tucson, Arizona to Mesilla, New Mexico, and from Safford, Arizona to several hundred miles into Mexico. The United States military sought Cochise, but he proved far too elusive when chased, and far too effective a commander in battle. He was also unrivaled with a spear. The Chiricahua people were more adapted to the land, better at hiding in it, and had better knowledge of it than United States soldiers. The military had many fights with Cochise and the Chiricahua Apache, but no single fight ended the war.The people of the United States did not understand Native American culture very well. They did not understand the separation between tribes. For example, they often thought the actions of one tribe were directly tied to that of another. This was rarely the case. Lieutenant Howard B. Cushing fell victim to this very ignorance. Cushing was attempting to pursue Cochise while another Chiricahua leader, Juh, (pronounced “who”) was pursuing him. Every time Cushing’s party got in skirmishes with Juh, Cushing assumed he was closing in on Cochise. However, he could not have been farther from the truth. Juh’s band eventually ambushed and killed Cushing. General Crook Comes to ArizonaGeneral George R. Crook was a stoic man. He graduated from West Point near the bottom of his class. After some success in the Civil War, he was hired to “fix the Apache problem.” He was a discreet and calculating man, speaking rarely and listening carefully.Crook chose to ride a mule while in the Southwest. He felt it handled the heat and terrain better than a horse. He also developed the use of pack trains. Whether the task was battle or hard labor, Crook usually worked on the front lines with his men. Crook witnessed firsthand the ineffectiveness of the white man at tracking the Apache. He came up with perhaps the United States' most effective strategy in the Apache Wars--tracking Apache with defected Apache. He would later recall his time in the Apache Wars as some of the most difficult work of his life.

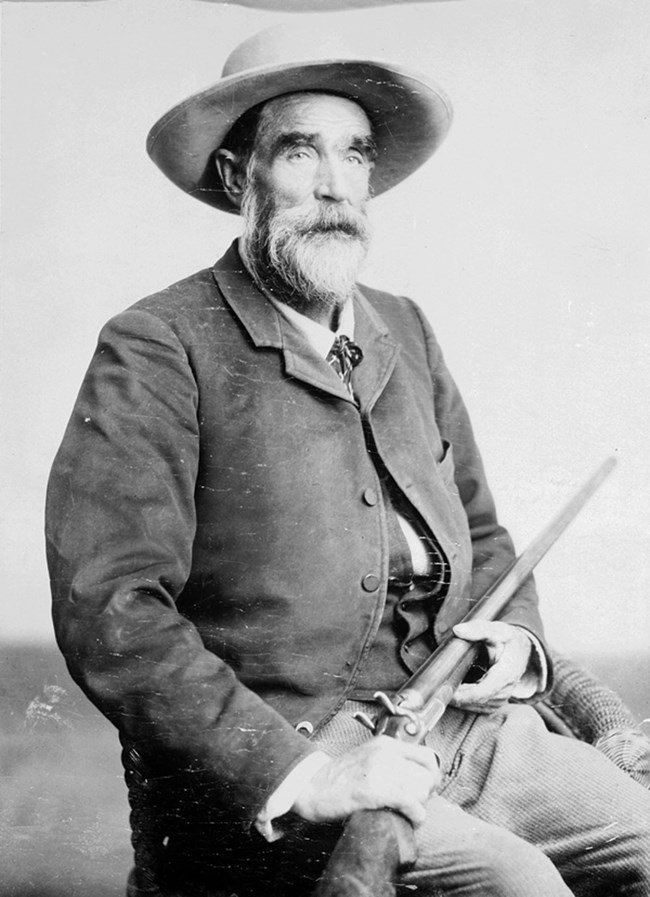

Public Domain Reservation ProposalsFinding or defeating Chief Cochise had proven futile for the U.S. Army. The strategy shifted to relocating him and the Chiricahua Apache to a reservation. Cochise was tired. He and his people had found life on the run and in hiding exhausting. The Chiricahua were very effective warriors. They were often able to take down many soldiers before falling. However, the U.S. had what appeared to be an inexhaustible supply of soldiers and provisions.Chief Cochise was asked repeatedly to meet and discuss relocating his people to a reservation. He would always refuse because reservations at the time had poor conditions. The San Carlos Reservation, for instance, had bad water, rampant sickness, mandatory role call, and forced menial labor which the people believed beneath them as warriors. Cochise bided his time and continued to avoid capture and defeat. The Chiricahua ReservationIn 1872, General O.O. Howard and Tom Jeffords, an Army scout, prospector, and employee of overland mail in Arizona, put their lives at risk by approaching Cochise Stronghold with few troops. When confronted by the Chiricahua, Howard and Jeffords told them they were not there to fight but to talk.Cochise made Howard and Jeffords wait several days before granting them entry into his camp. Cochise held an audience with Howard and the two entered into reservation talks. Both sides were very stubborn but after some time Cochise got the upper hand. Cochise procured a reservation for his people that spanned much of modern day Cochise County in southeast Arizona. The local newspapers slandered General Howard for giving up so much ground in the negotiations. Tom Jeffords became agent of the reservation. He would go on to become a Native American sympathizer, as well as the only white man Cochise ever considered a friend. On the reservation, the Chiricahua were able to roam free and camp wherever they wanted. There was no roll call taken. They were even allowed to leave the reservation, and often raided in Mexico, which stirred tensions. The reservation brought about a peaceful period in the war which would last four years. Settlers did not approve of the reservation’s loose authority over the Chiricahua. In Washington, D.C., the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of War fought over jurisdiction of the reservation. Given the peaceful period, however, General Crook headed north to fight with Lieutenant Colonel George Custer in the Dakotas. The Death of CochiseCochise began experiencing intense stomach pains and could not always eat. In 1874, he died of what was likely stomach cancer. The whereabouts of his grave are still unknown, though it is thought to be somewhere in his Stronghold. Cochise was one of the Chiricahua’s most effective leaders during the time of the Apache Wars. He was the only one able to bring prolonged peace and freedom to his people, even if it did not last long after his death.With Cochise’s death, the Chiricahua were left without a strong central leader. The U.S. government saw a chance to close the problematic Chiricahua Reservation. The final straw came when two Chiricahua warriors killed two white men for not selling them whiskey. The government fired Agent Jeffords and abolished the reservation. A New Reservation AgentAround this time, John Clum became agent of the San Carlos Reservation in east central Arizona. He was a notoriously pompous man. The Apache would nickname him the “Turkey Gobbler” because they thought he walked like a turkey. Clum travelled to the Chiricahua Reservation to order all the Chiricahua people to the San Carlos Reservation. He met with Cochise’s son, Taza, who had taken up the mantle of chief as his father had prepared him to do. Also at the meeting was Juh, whose brother-in-law often spoke for him because Juh had a stutter. Juh’s brother-in-law’s name was Goyakla. He was also known as Geronimo. |

Last updated: April 7, 2023