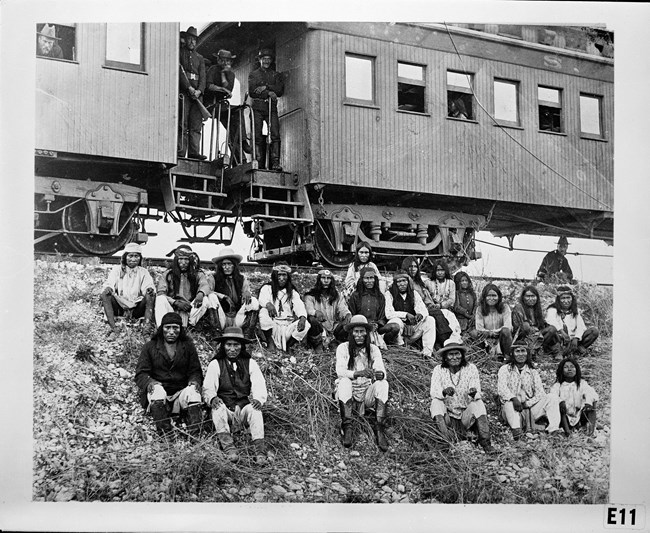

Public Domain/National Archives, Department of Defense

Public Domain/National Archives, 530797. The Surrender at Skeleton CanyonGeronimo's fourth and final surrender was in Skeleton Canyon in southern Arizona, the summer of 1886. General Nelson Miles took the credit. One of the conditions of the surrender was that the free Chiricahua Apache would see their families upon arrival in Florida. President Grover Cleveland, however, was still expecting an unconditional surrender. Unbeknownst to the Chiricahua, Miles had decided that since Geronimo had broken all of his prior conditions of surrender, all terms agreed upon were now null. The U.S. government never intended to allow the Apache to see their families when they got to Florida.Departure for FloridaGeronimo and his band were taken to Fort Bowie, where Geronimo drank from Apache Spring one last time. It was at this site he had fought next to Chief Cochise 24 years prior at the Battle of Apache Pass. Geronimo was now 65-years-old. He took his last steps on his native land and entered a train car, for the first time in his life, bound for Florida. The U.S. government had rid itself of the “Apache problem” once and for all.On the train ride out to Florida, Geronimo’s band was afraid they would be killed at any moment. Upon arriving, Geronimo and his band were not reunited with their families at Fort Marion as promised. Instead, they were taken to Fort Pickens. They would not reunite with their families for over two years, breaking Miles’ terms of surrender. Many Chiricahua died of malaria while in confinement. A daughter was born to Geronimo while in confinement, though he would not find out until later. Life as Prisoners-of-WarThe first group of Chiricahua Apache who had been moved to Florida were dwindling due to malaria. They were moved to Mount Vernon in Alabama as prisoners-of-war. It was an unfamiliar landscape to them, in the tall trees instead of open desert plains. Their children were sent to schools in Pennsylvania to learn Christianity, English, and other aspects of the American lifestyle. Many of these children caught tuberculosis and died. Chiricahua parents back in Alabama began to hide their children so they wouldn’t be taken away. After two years of imprisonment in Florida, Geronimo and his band were moved to Alabama and were finally allowed to see their families once again.General Crook visited the Chiricahua in Mount Vernon. By this time, he had lost all respect for Geronimo and did not meet with him. Crook instead met with the other leaders of the Chiricahua. Crook publicly condemned the schools in Pennsylvania. He also suggested that the Chiricahua be sent to live at the Fort Sill Reservation in Oklahoma, which would be a more familiar environment to them. Crook died two months later. When the Chiricahua were moved to Oklahoma, there were only 119 left, after eight years being prisoners-of-war. It was the first time in eight years that they could once again hear the coyote howl and collect their prized mesquite beans.

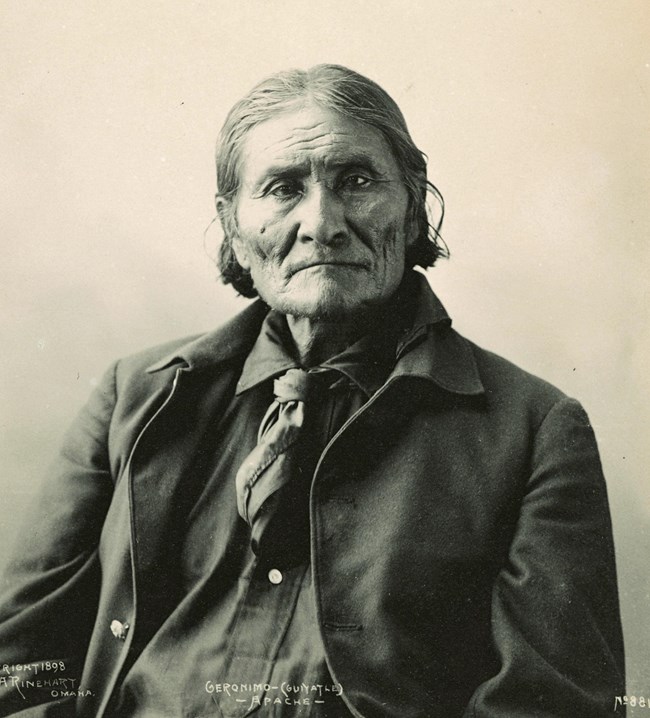

Public Domain/ Frank Rinehart Geronimo’s FameGeronimo, once known as the “worst Indian of all time,” had become one of, if not the most, famous. His already impressive deeds had been exaggerated again and again all around the country and the world. He toured the nation performing for fairs and exhibitions such as the Buffalo Bill Sideshow. He sold little trinkets such as buttons from his coat, which he could replace.Geronimo even rode in Teddy Roosevelt’s presidential election parade. It has been said that more people turned out to see Geronimo than Roosevelt himself. Geronimo asked the president if he and his people could return to the Southwest. Roosevelt refused, saying there was still too much hate for the Chiricahua in the Southwest. Geronimo’s EndAt the urging of settlers, Geronimo attempted to learn Christianity in his old age. He struggled, however, under Christian principles to forgive himself for all the killing he committed, especially children.An artist once visited Geronimo to paint him. The painter stated that Geronimo had revealed his bullet wounds to him and said that there were over 50. “Bullets cannot kill me,” Geronimo said--and they did not. In 1909, Geronimo was returning from a drinking binge one night when he fell off his horse into a ditch. He stayed in the ditch until morning and contracted pneumonia. Before he died, Geronimo stated that he never should have surrendered, but instead should have died fighting. He passed away days later. FreedomIn 1913, after twenty seven years of imprisonment the Chiricahua were finally set free and were no longer prisoners-of-war. One-third opted to stay at Fort Sill, while two-thirds moved to the Mescalero Apache Reservation, in New Mexico. At the time of Chief Cochise, the Chiricahua Apache had numbered 1,200. At the end of the war, in 1886, they numbered 500. By their release they numbered only 261. Today there are over 850 Chiricahua Apache. Descendants of Cochise and Geronimo still live on. |

Last updated: August 19, 2018