Left image

Right image

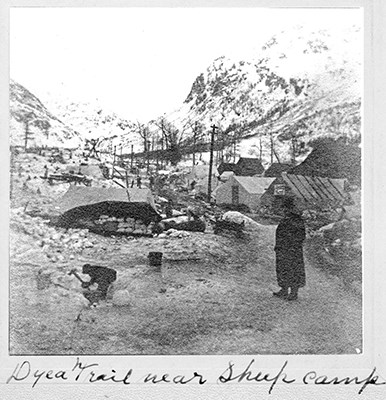

Pre- Klondike Gold RushSheep Camp has long been a stopping place for travelers crossing over Chilkoot Pass. It has proven popular because it was the last convenient camping area on the trail before timberline. It has probably been used for hundreds of years by Alaska Natives crossing to and from the Interior.Euroamericans continued this usage. Although neither Schwatka nor Ogilvie camped at Sheep Camp, it was used by many of the prospectors who headed north for gold between 1880 and 1896. For most, the passage was uneventful. However, in the spring of 1895, customs officers visited the camp and enlivened things by destroying three kegs and ten cases of liquor. Several stories have tried to explain the camp’s name. It probably came about because it was thought that sheep (actually mountain goat) hunters camped here. A less likely story is that a prospector drove a band of sheep over the pass, and camped here along the way. Other stories claim that the place was named “because of the number of mountain sheep formerly killed there,” or from “the mountain sheep which at one time were plentiful.”

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55751. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. Gold Rush CampNot until summer 1897 was a wooden structure built at Sheep Camp. Early photographs show a combination hotel and store existed on the east side of the river. A man named Palmer ran it. Alfred Daly, who traveled north in mid‑September 1897, termed it …a shanty where they had a floor. It was a kind of a hotel. You paid for the privilege of sleeping on the floor. The proprietor told us that if we didn’t get our blankets down on the floor very quickly, we couldn’t get room. He was right. The floor was full very soon.

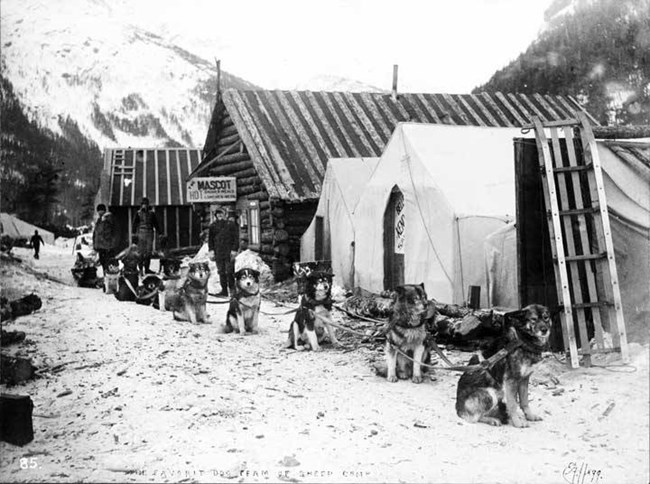

Alaska State Library, Eric A. Hegg Photo Collection, P124-02. Gold Rush BoomtownIn late January William Schooley noted that he had to get permission to camp in a certain spot near the trail. By mid February approximately forty log buildings had been erected. On February 28 the population had risen to between 350 and 400. By early April a formal post office had been established. The need for mail service had been obvious for months before that time, and in place of an official system, several informal post offices had been established in local stores. Merchants E. C. Stahl, Courtenay and B. S. Foss all ran private postal services. Local resident W. G. Seward was contracted to haul mail between Dyea, Canyon City, Sheep Camp, and Lake Lindeman. In April, Sheep Camp was booming. A Dyea newspaper reported that there was "scarcely an inch" of available ground in the area in which to camp, with "tents so thickly set as to prevent one passing between them in any instance." The main street was reportedly sixteen feet wide. The settlement was evidently quite large. Tents and buildings stretched across the narrow valley, and estimates of the town's length varied from one to two miles. A newspaper reported that within the camp there existed "two drug stores, a hospital, fifteen hotels and restaurants, coffee stands and lodging houses too numerous to mention." It also had "two laundries, a bath house and several store houses, numerous small stores and many saloons." The stores offered a …liberal display of such supplies and wares as are most needed in an Arctic mining camp. These stores are of rude and cheap construction, usually thrown together of such material as chanced to be most available, and without further architectural design than simply to afford shelter.

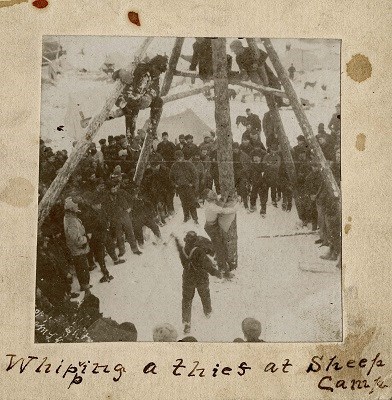

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rasmuson Foundation, KLGO 55811. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. …neither law nor order prevailed, and honest persons had no protection from the gangs of rascals who plied their nefarious trade. Might was right; murder, robbery and petty thefts were common occurrences. Sheep Camp residents made only the merest attempts at government. A plat map was drawn, but it has since been lost. Most persons did not bother to record their lots, and few of those that did referred to the existing plat. Regarding the public protection, a fairly long lasting citizens' committee was organized against the lawless element noted above. It also assisted in the identification and burial of the victims of the Palm Sunday avalanche in April 1898. Packers along the Chilkoot, like those on White Pass, were notoriously cruel to their pack animals. The horses along the trail suffered from neglect and abuse. At Sheep Camp it was common for packers to abandon their animals. Several stampeders commented on the pathetic sight of the starving animals wandering about camp and tripping over the guy wires of the tents. Some took the merciful alternative and shot animals that appeared to be too weak to continue. One stampeder came upon a dead horse while shoveling snow for his tent site. Another noted, "the many dead horses and dogs scattered about the camp."

Like Canyon City, White Pass City, Log Cabin, and other trailside towns, Sheep Camp sprang up because it was a logical, comfortable stopping place along the trail. Each town began as a simple camping spot, but each soon developed a strong business base, one which, was well adapted to the needs of the passing miners. Photographs, diaries, newspapers, and other sources have noted that the following known businesses existed in Sheep Camp at some time during the winter of 1897-98:

16 hotels or lodging houses

14 restaurants 13 stores or supply houses 5 doctors or drug merchants 3 saloons 3 transportation companies 2 dance halls 2 laundries 4 miscellaneous businesses (lumber yard, bath house, storage, hospital) 52 businesses (total is less than accumulated subtotals because several businesses served more than one function) The condition of these buildings varied greatly. The hotels, as a rule, were usually wood frame buildings. They were often two stories high; with the possible exception of the dance halls, they were the only buildings in town known to exceed one story in height. Diaries show that the hotels were simple at best. Most patrons were simply offered large rooms where a communal floor was shared. Most hotels were of board and batten construction. Most of the other businesses were located either in whole log buildings or in vertical walled tents. Some of the smaller businesses were situated in smaller tents, and a few were open-air operations. Some of the hotels and a few of the other businesses advertised on large wooden signs. Others announced their wares on pieces of canvas, on the side of their tents, or on small boards. A small Alaska Native camp existed in Sheep Camp during the winter of 1897 98. In the area of the camp, a sign proclaimed that "George II is Chief of the Chilkoots and a friends [sic] of all white men." Many of the inhabitants were hired here to make the climb over the pass. In the first few months of 1898, a line, used for telephone purposes, was constructed by the CR&T tramway company. It paralleled the CR&T tramway line, traveling just east of the line, through the entire townsite. This company's distinctive two crossbar poles are seen in many historical photographs. This line was completed in February 1898; Sgt. Steele used it to call Dyea from the Scales on February 23. The population of Sheep Camp, like the other Chilkoot Trail camps, rose during the fall and winter of 1897-98 and fell thereafter. It was probably at its height between February and April 1898. Estimates of its peak population ran between six and eight thousand. John P. Clum estimated that it averaged seven thousand for two months. Another source has quoted that there were "seldom fewer than fifteen hundred people" there during the gold rush. Despite the bustle and activity, all knew it was temporary. One stampeder wrote in his diary that "no one expects it [Sheep Camp] to last longer than this spring."

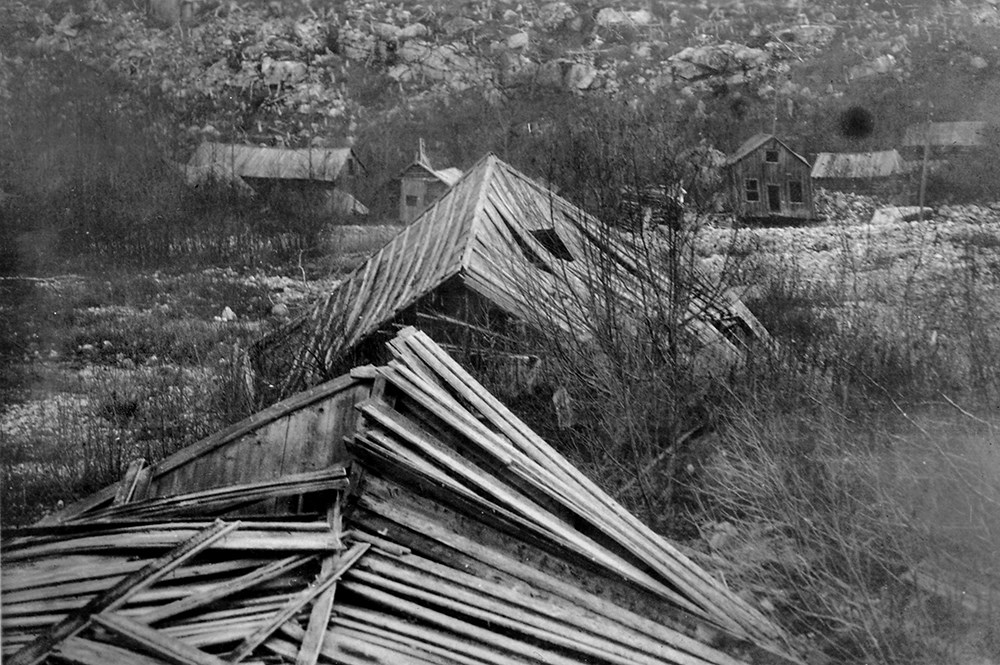

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59779e. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. Post Gold Rush DeclineWith the coming of summer, the flood of stampeders predictably slowed to a trickle. The coming winter did not bring a renewed wave of stampeders, and by July 1899, only 18 people remained in the town. The last shred of an economic base at Sheep Camp was removed when the CR&T Company tramway system shut down that summer. The post office closed on October 21, 1899. The town was probably vacated soon afterwards. It continued to loom as a major site in the minds of railroad promoters for the next several years, but none of the proposed lines ever got beyond the survey stage.The remains of the abandoned town decayed slowly. In September 1906, when the Leland Boundary Survey passed through, most of the buildings were still standing. In 1924 longtime Skagway resident George Rapuzzi visited the area. As he remembered it, “there was lots of Sheep Camp intact then, it was as good as before.” At the time a Hollywood director was planning a movie on the gold rush, and he envisioned restoring Sheep Camp to its former appearance. He also planned to build a road up to the camp. The director hiked up to Sheep Camp with a small crew, and reportedly took “a huge amount” of movie footage of the area before returning south. For an unknown reason, the movie was never made with Sheep Camp as a location, and plans for the road were dropped. At about the same time Charlie Chaplin directed and starred in “The Gold Rush,” which was filmed in Nevada and California. The continued passage of time caused further disintegration of Sheep Camp. Between the gold rush and the 1950s, it is probable that at least one party of hikers crossed over Chilkoot Pass each year, and other parties hunted up in the Sheep Camp area. Inevitably, some items were removed from the site by souvenir collectors. Others were removed for preservation and display. The following advertisement appeared in a Skagway newspaper in the late 1920’s; Liquor Shakers and Bibles,

Guns and Yukon Stoves, Roulette Tables and Packs!!! Abandoned at Dyea and Sheep Camp by the Trail Weary Cheechakoes!!! Now at the Museum of ‘98. It is doubtful, however, that early post Klondike visitors to Sheep Camp removed many items, nor impacted the buildings themselves. A more destructive force to the townsite was the Taiya River. Most buildings in Sheep Camp were located within a hundred yards of the river. Springtime floods have probably caused the river to change course several times since the gold rush. As early as 1911, it was noted that “the river has cut the town up considerably in its wanderings, but several of the old buildings still remain.” As a result, many of the camp’s most prominent buildings have been obliterated, and the present day course of the river south of central Sheep Camp is between one hundred and two hundred feet west of its historical course. The construction and improvement of the recreational trail by the State of Alaska has brought further change to the area. For instance, two recreational trail routes have passed through the camp. In 1966, the old trail section was discovered and the trail was rerouted to cross in front of the Sheep Camp shelter, cross a small stream and proceed northerly to join the old trail. Modern Sheep CampSince trail construction began several new buildings have been constructed. A trail shelter was built by 1963 by the Alaska Youth and Adult Authority. In 1973 the nearby ranger station complex was flown in from Glacier Bay National Monument and installed. The loss of many historical artifacts has also been observed. The tens of thousands of hikers in the last twenty five years have been responsible for collecting hundreds of artifacts. One notable loss was a huge pile of horseshoes located near the Sheep Camp shelter. The remains of a large, disturbed artifact area were noted in 1979. Hikers have also, either accidentally or intentionally, contributed to the destruction of several historical buildings located on or near the trail. Field surveys in the late 1970s identified 23 structures, five structural scatters and eight foundations. Surveys in the early 1980s catalogued and photographed 160 non structural artifacts at the townsite.Today Sheep Camp is an important stop along the Chilkoot Trail. This is the last campground before hikers head up Long Hill to the Scales, and then over Chilkoot Pass. As a result, the Sheep Camp campground is often one of the fullest and most bustling stopping places along the trail in the summer. |

Last updated: January 28, 2020