Steve Yeager In the late 1990s, all that remained of the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep was six herds numbering 125 total animals scattered along the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada. Facing imminent extinction, the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep was listed as a federally endangered subspecies in 1999. The reality of the fate that had recently befallen these bighorns brought an increased urgency to an extraordinary effort already underway to save this subspecies from extinction. The quest to save these wild sheep provides one of the most gripping yet heartwarming chapters in Yosemite National Park’s history.

The security of the wild sheep’s undisturbed habitat was breached soon after the California gold discovery by settlers with their guns and disease-carrying domestic sheep. Lacking natural resistance to certain diseases transmitted from domestic sheep, infected herds began dying out in the 1870s in a progression of losses that continued to the mid-20th century. Only 24 years after the designation of Yosemite as America’s third national park, rangers in 1914 noted the absence of bighorns within the park’s boundaries. Any hope that herds in adjoining wilderness lands would move to restore the Yosemite herds were dashed when all adjacent herds also perished. The only bighorns to survive 75 years of decimation were in the southern Sierra. By 1978, three herds totaling only 250 animals were all that remained of the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep, and that number reflected an apparent recent population increase from much lower numbers.

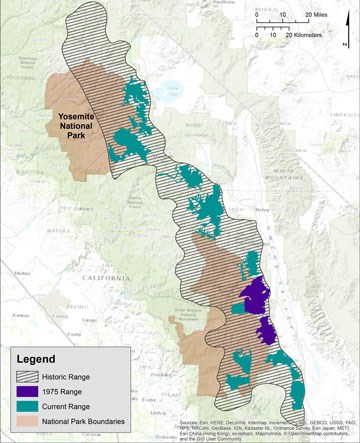

In 1981, the near extinction of this wilderness icon resulted in the initiation of a pivotal and timely collaborative effort between the National Park Service and other agencies, known as the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Interagency Advisory Group (SNBSIAG). The formation of this group resulted from a recommendation by the pre-eminent Sierra bighorn researcher, Dr. John Wehausen, who played a central role in this advisory group through its existence. This group continued the important work of restoring Sierra bighorn to their historical habitat that Dr. Wehausen had initiated in 1977 as a graduate student. Biologists successfully reintroduced three herds during 1979-88, and under the guidance of SNBSIAG, released 27 bighorns in Lee Vining Canyon, east of Tioga Pass, in 1986. Because the western edge of this area included Yosemite National Park lands, this herd became known as the Yosemite Herd, and the specific goal of that reintroduction was to return this iconic species to that park. This important event heralded the restoration of the animal that John Muir called “the bravest of all the Sierra mountaineers” to Yosemite National Park after an absence of over 70 years. In its first year, the Yosemite Herd split into two herds, the Mt. Warren and Mt. Gibbs herds, with sheep in the Mount Gibbs herd moving seasonally between Inyo National Forest lands and the high-elevation border with Yosemite National Park. Overall, these fledgling sheep herds initially lost numbers, in part due to mountain lion predation, until that trend was reversed by an augmentation of 11 more sheep to Lee Vining Canyon and the initiation of mountain lion control in 1988. Those efforts worked and, by 1994, the total population was approaching 100 animals; but sheep were increasingly avoiding use of low-elevation winter range in Lee Vining Canyon, where mountain lion control ceased after a state initiative in 1990 made mountain lions a specially protected mammal. The winter of 1994-95 proved to be devastating for some Sierra bighorn herds that appeared to be avoiding mountain lion predation on lower elevation winter ranges by attempting to live year round at high elevations. The Mount Warren herd was one of those, with only 34 sheep in the Mount Warren and Mount Gibbs herd surviving that winter. All bighorn herds in the Sierra Nevada experienced similar major population declines in the 1990s after shifting winter habitat use patterns away from lower-elevation winter ranges. Despite the wholehearted efforts of SNBSIAG, by 1995, the total population of Sierra bighorn was about 115—38% of their numbers a decade earlier. Following little subsequent population increase, late in 1998 SNBSIAG, decided to pursue endangered species status for these sheep. In 1999, Dr. Wehausen drafted petitions for state and federal endangered status. A quote from The Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Foundation, one of five environmental organizations that submitted petitions, conveys the depth of concern for the animals: “Beyond the profound ecological consequences of extinction, the loss of the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep would have repercussions across centuries of natural and human history, leaving this great mountain range impoverished forever.” Both the California Fish and Game Commission and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service quickly granted endangered status to these bighorns in 1999. The federal designation was vital in allowing control of mountain lion predation on bighorns because federal law supersedes state law. The California State Legislature, reacting to media attention over the fate of Sierra bighorn, in a rare almost-unanimous vote, approved a change in the 1990 initiative to allow control of mountain lions to protect bighorn sheep in California. In another unprecedented action, that legislature also initiated financial support for a state-led recovery program for these sheep—a program that continues today. Such action by the state legislature for an endangered species was—and remains—unprecedented. One of the first accomplishments of that program was the drafting of a recovery plan. With the endorsement of the people of California, and backed by both federal and state law and ample funding, the survival of the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep became dependent on the success of the recovery plan. The plan called for monitoring population growth and carrying out augmentations and translocations in an effort to reach recovery goals. GPS collars on sheep and mountain lions provided the means for collecting scientific data to understand habitat use and cause-specific mortality of sheep. Recovery team members and biologists provided vital data analyses and management adjustments as the program progressed. With each lamb that was born and survived, the odds of success grew greater. With the recovery program led by a highly committed scientific leadership team, whose members cared deeply about the fate of the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep, the fragile number of bighorns began to increase over the next decade. The Mt. Warren herd, whose numbers had plummeted, was augmented with additional bighorns, and with the survival of each lamb their populations began to grow. By 2014, over 600 Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep were living in their ancestral homelands along the crest of the Sierra Nevada—a stunning and most gratifying success for the members of the recovery program. The Cathedral Range of the Yosemite Wilderness became the location for one of the most inspirational and recent bighorn restorations, carried out in March 2015. At its north end, Cathedral Peak, one of Yosemite National Park’s most prominent and famous landmarks, anchors this mountain range in the heart of Yosemite National Park. To read a description of Cathedral Peak from the 1863 California Geological Survey team who named it, is to understand its symbolic importance in restoring Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep to their ancestral homeland: “From a high ridge, crossed just before reaching this lake [Tenaya], we had a fine view of a very prominent exceedingly grand landmark through all the region, and to which the name of Cathedral Peak has been given… the majesty of its form and its dimensions are such, that any work of human hands would sink into insignificance if placed beside it.” Biologists successfully returned bighorns to the Cathedral Range on March 26, 2015. Ten ewes and three rams were airlifted by helicopter into the mountain range, where they were released and almost immediately found a rocky perch. Months later, two lambs had been born and the herd was deep in the Cathedral Range, climbing steep terrain and foraging on summer flowers, grasses, and a variety of other forages. The restoration of Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep to Yosemite’s Cathedral Range has been an important milestone in many ways. It coincided with the completion of bighorn restoration to all geographic areas initially identified as critical in the recovery plan. Yosemite National Park celebrated the return of a long-lost wilderness icon to its wilderness heartland, an event covered by world-wide media. And most importantly, the restoration of the wild sheep to such a mountain range invoked thoughts of how close the animals had come to perishing forever, and what that would have meant to us as people. To witness the bighorns sprinting toward the granite boulders of the Cathedral Range, already at home, lifted everyone’s spirits that day with the thought that their work, and the wishes of Californians, had returned the wild sheep to the deep wilderness of one the best known national parks. And for the thousands of people worldwide who heard the story, it brought a quick moment of joy. A good deed had been done. Animals known to many people as a wilderness icon had been moved one more step back from the extinction precipice. It could not have happened in a better place: Yosemite. |

Last updated: October 1, 2024