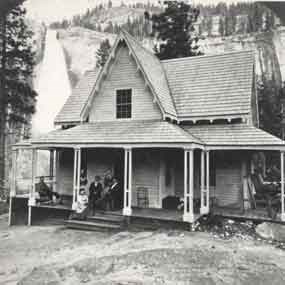

Yosemite Research Library: Negative 1647

Situated within the spray of Nevada Fall stood a pioneer hotel operated by Albert and Emily Snow. For close to 20 years, the Snows welcomed guests to their picture-perfect setting at La Casa Nevada—a fitting name meaning The Snow House—at 5,360 feet. When describing the inn’s elevated location, witty Emily Topple Snow would say: “Seven hundred feet above the level of the Valley; just as near to heaven as you’ll get.” Outdoor enthusiasts trekked to Yosemite to view the park’s glorious waterfalls—created, in this case, by the roaring Merced River’s leap down the side of a granite cliff. Yosemite innkeepers, like the Snows, provided a valuable service as one of nine Valley hotels in the late 1800s.

RL-16,481 It’s uncertain when the New England couple left Vermont for California, but it’s known that F. Albert Snow operated the Washington Hotel in Groveland, California, in the 1860s. After the Act of Congress in 1864 to set aside Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to the State of California as a grant, Albert considered a business move. In 1869, he sought permission from the grant’s board of commissioners to construct a hotel at the base of Nevada Fall and to build a toll trail from the end of the existing Vernal Fall Trail up to Nevada Fall. His savvy timing took advantage of increased visitation to the area after the completion of the transcontinental railroad; the park counted more than 1,200 visitors that one year. Rugged Albert blazed a horse trail, zigzagging from Register Rock on the Vernal Fall Trail up to Clark Point to the flat between Vernal and Nevada falls, and loaded mules to haul heavy building materials needed to construct a simple hotel in a complicated location.

RL-16,459 The first guests to the one-story lodging, initially named the Alpine House, signed the register on April 28, 1870. The Alpine House was principally a lunch stop by foot or by horse, as the two falls—Vernal and Nevada—were a must-see for Yosemite visitors. Some travelers stayed overnight before or after hiking to Glacier Point. At the inn, guests took in unobstructed views of Nevada Fall from the hotel’s veranda while they took in plenty of refreshment. Early travelers wrote in the hotel register of their tasty experience dining on Emily’s elderberry pies, doughnuts, baked apples, bread and baked beans. They also mentioned the easily-accessible liquor: “Be sure to try the Snow water” and “No person here obliged to commit burglary to obtain a drink.” (Also validated by the rubble of broken bottles on the rocky flat found throughout the years.)

RL-13602 Pioneer women, like Emily, supported their husband’s lodging ventures by preparing meals for guests. The slender Emily wore a tidy floor-length dress with little white collar and pulled-back hair as prim as an old maid, yet she offered humorous quips. She told visitors, “You folks would hardly think of it, but there was 11 feet of snow here all summer.” When asked how that was possible, she replied, “Well, my husband is near 6 feet tall, and I’m a little over 5. Ain’t that 11?” A year after the hotel opened, an expansion doubled the size of the Alpine House. This 1871 addition was shaken into disrepair by an 1872 earthquake, however, east of the park, causing the structure to jump two inches to the east. But, after another expansion by 1875, the Alpine House became known as La Casa Nevada. The hotel included the 12-room original building, 10-bedroom chalet, woodshed, icehouse, log cabin and stable. James Mason Hutchings praised his hard-working Valley neighbors in his 1886 book, In the Heart of the Sierras: “Snow’s La Casa Nevada has become deservedly famous all over the world, not only for its excellent lunches and general good cheer, but from the quiet, unassuming attentions of mine host, and the piquant pleasantries of Mrs. Snow. … And, although they do not know whether the number to lunch will be five or fifty-five, they almost always seem to have an abundance of everything relishable.” Summers for the Snows meant working La Casa Nevada while winters meant a move to Groveland, near their daughter Maria who married an area rancher named Colwell Owens Drew. As winters let loose, the Snows returned to their Yosemite cliff hotel in April of each year, accompanied by a mule train bringing more foodstuffs and spirits. Forced by advancing age, the Snows, however, gave up La Casa Nevada in the fall of 1889. Emily died within weeks that year, and Albert died in 1891. La Casa Nevada continued loosely as a lodging facility for the next two years, run by D.F. Baxter. Granted the 1890 and 1891 lease, Baxter quietly relinquished it. For the remains of the decade, La Casa Nevada’s front desk received no guests except for the few visitors who entered to sign the register as their support for the failing facility. (That register, a three-volume recording, has become one of the most prized possessions of the Yosemite Museum collection.) An accidental fire, in 1900, burned down the decaying hotel, and the structure’s remaining wood was used as firewood by passersby. Today’s passersby must imagine the intimate hotel in its picturesque spot, reverting to a quiet wilderness but still resounding with the beauty that once attracted the Snows. Sources

|

Last updated: July 23, 2024