NPS / Jim Peaco

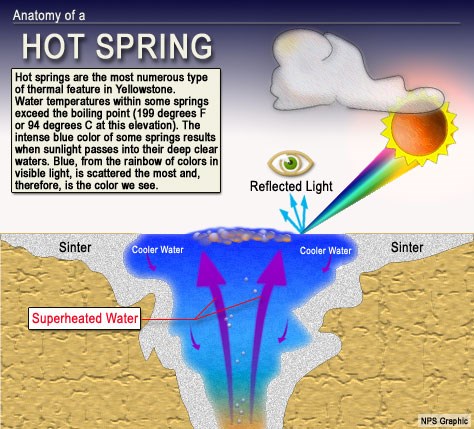

NPS Hot springs are the most common hydrothermal features in Yellowstone. Beginning as precipitation, the water of a hot spring seeps through the bedrock underlying Yellowstone and becomes superheated at depth. An open plumbing system allows the hot water to rise back to the surface unimpeded. Convection currents constantly circulate the water, preventing it from getting hot enough to trigger an eruption. At times, fierce, boiling waters within a hot spring (such as Crested Pool) can explode, shooting water into the air, acting much like a geyser. It is believed, however, that in the case of Crested Pool, no constrictions block the flow of water to the surface. The spring's wide mouth and 42-foot depth provide a natural conduit for superheated water to circulate continuously to the surface. Hot Springs ColorsMany of the bright colors found in Yellowstone's hydrothermal basins come from thermophiles—microorganisms that thrive in hot temperatures. So many individual microorganisms are grouped together—trillions!—that they appear as masses of color. Different types of thermophiles live at different temperatures within a hot spring and cannot tolerate much cooler or warmer conditions. Yellowstone's hot water systems often show distinct gradations of living, vibrant colors where the temperature limit of one group of microbes is reached, only to be replaced by a different set of thermophiles. More Information

Hydrothermal Systems

Yellowstone's hydrothermal systems are the visible expression of the immense Yellowstone volcano.

Life in Extreme Heat

Hydrothermal features are habitats for microscopic organisms called thermophiles: "thermo" for heat, "phile" for lover. |

Last updated: April 18, 2025