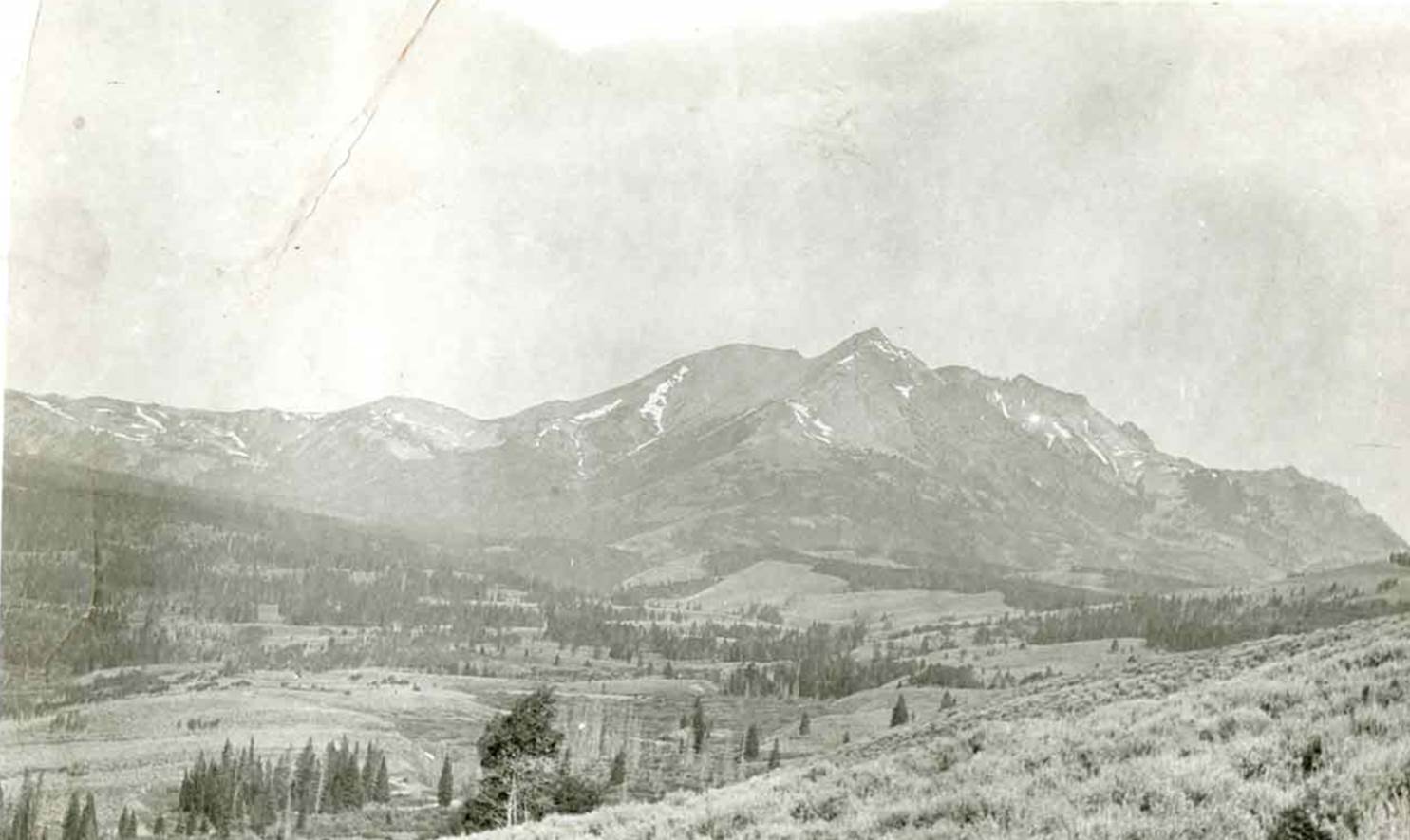

Electric Peak with Gardner River in foreground. (YELL 1592)

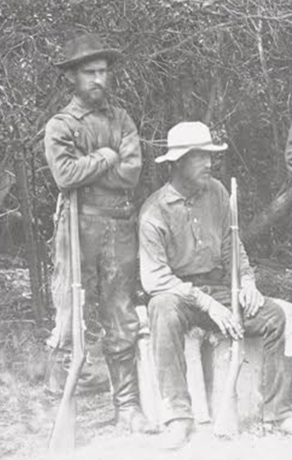

Later a celebrated geographer with the United States Geological Survey, Henry Gannett was only 25 years old when he joined Ferdinand Hayden’s 1871 expedition through the as yet unsurveyed territory that would, the following year, become Yellowstone. As the mission’s chief geographer, his primary responsibilities included taking astronomic, meteorological, and hypsometric measurements. One specific responsibility involved determining the precise elevation of the region’s most prominent point, a jagged and imposing point in southwest Montana territory which dominated the surrounding area. In order to gather the measurements necessary for the calculation, it proved essential to summit the daunting peak. On the morning of July 26th, accompanied by two other members of the party—mineralogist Albert Peale and assistant T. B. Brown—the surveyor began the ascent. Hauling an assortment of cumbersome but fragile scientific instruments, including an astronomical transit, mercurial barometer, sextant and artificial horizon, among other devices, the party worked their way slowly skyward.

Peale and Gannett (seated) in 1875. (YELL 7570)

As the trio trudged closer to the summit, scrambling over the peak’s loose and treacherous sandstone and volcanic rocks, nature was conjuring a yet more dangerous obstacle. “When we were within about 500 feet of the top,” Peale reported in his contribution to the Sixth Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, the official federal report of the survey, “a storm came up and we were enveloped in clouds…. Mr. Gannett succeeded in attaining the highest point and depositing his instruments, when he discovered that he was in the midst of an electrical cloud, and his feelings not being of the most agreeable sort he retreated. As he neared us we observed that his hair was standing on end, as though he were on an electrical stool, and we could hear a series of snapping sounds, as though he were receiving the charges of a number of electrical frictional machines.”[1]

In Gannett’s account of the event, he described the sensations that Peale had observed: “when about 50 feet below the summit the electric current began to pass through my body. At first I felt nothing, but heard a crackling noise, similar to a rapid discharge of sparks from a friction machine. Immediately after, I began to feel a tingling or pricking sensation in my head and the ends of my fingers, which, as well as the noise, increased rapidly, until, when I reached the top, the noise, which had not changed its character, was deafening, and my hair stood completely on end, while the tingling, pricking sensation was absolutely painful.”[2]

The wild, early afternoon storm continued to wreak havoc, whipping the men to and fro. Electrical activity in the atmosphere elicited unfamiliar physiological sensations as it encroached upon and permeated their bodies. Despite the palpable danger and physical pain, Brown remained determined to attain the summit. Managing to proceed only a few feet further, he received a significant shock, “which felled him as if he had stumbled.” At the storm’s insistence, the party finally retreated several hundred feet downward. Though all three were ultimately unharmed and did successfully summit the mountain after the storm blew over, the experience so shook Gannett that he dubbed the 10,969-foot[3] massif “Electric Peak,” a name which it boasts to this day. [4]

Cross section of Madison Valley, west of Electric Peak. (Survey of the Territories, 62)

In 1872, the scientific explanation of what electricity was and how it functioned remained unsettled, though the energy was typically modeled as a “fluid” which moved and behaved in a way analogous to a liquid or gas. Encounters with lightning and other forms of electricity in nature—such as Gannett, Peale, and Brown’s—were integral to the development and refinement of new and more sophisticated theories and models of what electricity was believed to be and how it was thought to function in nature.

Despite the frightening and dangerous elements of the 1872 ascent, later scientists, mountaineers, and park advocates remained inspired by Yellowstone and Electric Peak’s remarkably high electrical activity. In his 1901 volume, Our National Parks, celebrated naturalist John Muir wrote of Yellowstone that “the air is electric and full of ozone, healing, reviving, exhilarating, kept pure by frost and fire, while the scenery is wild enough to awaken the dead.” Believing that Yellowstone and Electric Peak possessed healthful and restorative qualities, Muir urged those of weak constitution to “try to climb Electric Peak when a big bossy, well-charged thunder-cloud is on it, to breathe the ozone set free.”[5]

Today in Yellowstone—a landscape with no shortage of remarkable features—Electric Peak remains one of the most arresting. One can view it from many places in the northwest portion of the park, just as Henry Gannett did in July of 1871.

[1] United States Geological Survey (U.S.G.S.), F. V. Hayden, comp., Sixth Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1873), 121.

[2] Ibid, 807.

[3] Gannett originally calculated Electric Peak to be 10,992 feet high, though this number was later revised to the currently accepted elevation.

[4] U.S.G.S., 807.

[5] John Muir, Our National Parks (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1901); 40, 59.