And Nothing Less: Episode 2, Myths and Legends

Rosario Dawson: Ok so let’s start at the beginning

Retta: (singing) A very good place to start!

RD: I’ll just google ‘when does the suffrage movement begin?’ [typing noises]. Okay, this first entry tells me ‘The woman suffrage movement actually began in 1848, when a women's rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York.’

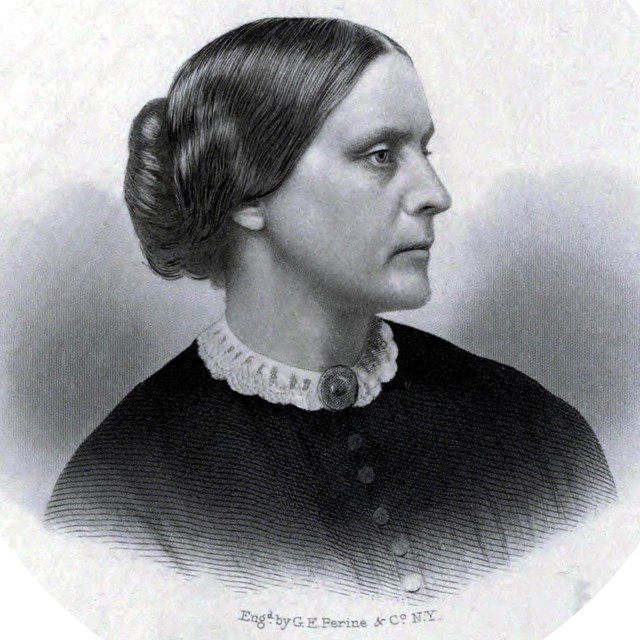

R: Oh yeah: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were there. And they led the fight until 1920 when all women got the vote. I feel like that’s kind of how I learned it, right?

RD: Right! Sally Roesch Wagner: Every piece of that is wrong. R & RD together: Oh (defeated) Wagner: First of all, we don't begin the story with 1848. We begin it a thousand years ago When Haudenosaunee women had political voice on this land R: That’s historian and suffrage fact-checker Sally Roesch Wagner. WAGNER: Susan B Anthony was not in Seneca Falls in 1848. RD: There’s a lot that’s wrong about this. WAGNER: history in some ways becomes a telephone game. You know, one person tells the story and then the other person picks up that story. And it isn't until sometimes we get an anniversary like the centennial when history, which is usually on the back burner, is moved to the front burner. And we have a chance to examine this story that we've been telling and seeing. Did we miss anything? Boy, did we miss a lot. [theme music]

RD: Today we’re gonna fix that.

R: It’s time for some serious fact checking. I’m Retta

RD: And I’m Rosario Dawson. And this is And Nothing Less. Episode Two -- Myths and Legends

[SENECA FALLS audio]

R: When we tell the story of the 19th amendment, one of the most well-known parts is the beginning, at Seneca Falls.

[opportunity for live sound there]

R: This is the site of the first women’s rights convention in 1848. Seneca Falls, New York. It’s in the Finger Lakes region of the state, and now it’s home to a national park.

RD: We’re correct to call this the first, if we’re clear we mean the first women’s rights convention. But this was NOT the beginning of the movement. Women have been gathering and advocating for their own rights for as long as they wanted to have them.

R: This is especially evident when you look at the history of African American women organizing, says Martha Jones. She’s the author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.

martha: So even before, for example, the Seneca Falls convention, African-American women, black Methodist women have been organizing and advocating within their church community for political power. What that means before the civil war in particular is black women have been organizing and advocating and in some cases winning the right to preaching licenses to have religious authority, the authority and access to the pulpit within their religious communities.

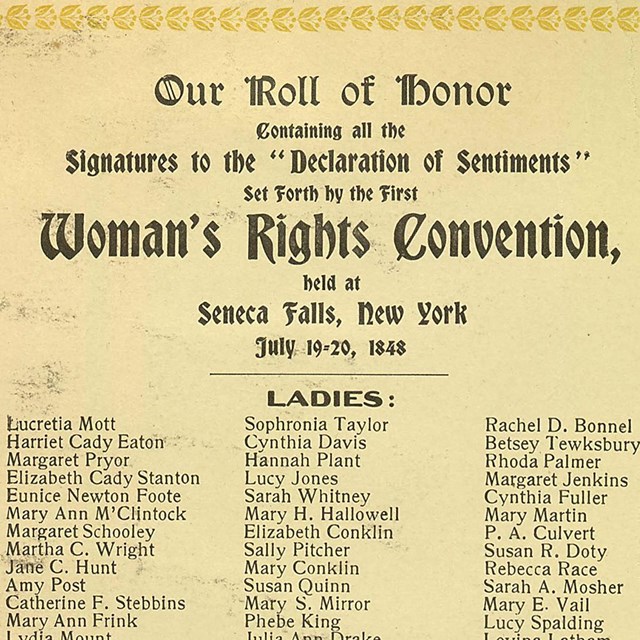

RD: So what actually happened at Seneca Falls? And why has it become such a big part of the suffrage story? Carnegie Mellon Historian Lisa Tetrault actually wrote a book on this called, aptly, The Myth of Seneca Falls. Tetrault: when you talk about the suffrage story, it's often narrated as a single story. Beginning in 1848 and ending in 1920. 1848 is when the first women's rights convention in the US was held, or at least something named explicitly. The first women's rights convention was held in western New York in Seneca Falls, New York. Elizabeth Cady Stanton had settled there. She was a newlywed. She had married an abolitionist and knew some people in the abolitionist circles, a very distinguished one. Lucretia Mott came through the town and invited Stanton for tea. And as the story goes, Elizabeth Cady Stanton poured out her domestic woes over a tea table. And then there are these five women decided they would hold a convention to protest women's wrongs. RD: And then after spilling the tea at Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s home -- sorry it was too easy -- Stanton and Lucretia Mott placed a little ad in the local newspaper and just short of two weeks later, they held a convention. Tetrault: In that time they wrote something called the Declaration of Sentiments, which was like their women's rights manifesto that they read at the convention, which took place over two days. And then they all a bunch of them signed it. 300 people showed up. [AMBIEND SOUND FROM PARK] Andrea: we're standing right next to the Wesleyan Chapel, where the first women's rights convention was held on July 19 and 20 of 1848.

RD: That’s Andrea Dekoter acting superintendent of the Women's Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls.

Andrea: The Declaration of Sentiments says when in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the Earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them.

RD: And there’s one line in particular that really sticks with Dekoter.

Andrea: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal.

And, you know, whenever I read that, I just have this moment where I have to pause after saying that all men and women are created equal. Because think about the shock and the chills that that that met with when they read it for the first time at the convention.

[AMBIENT SOUND fade out]

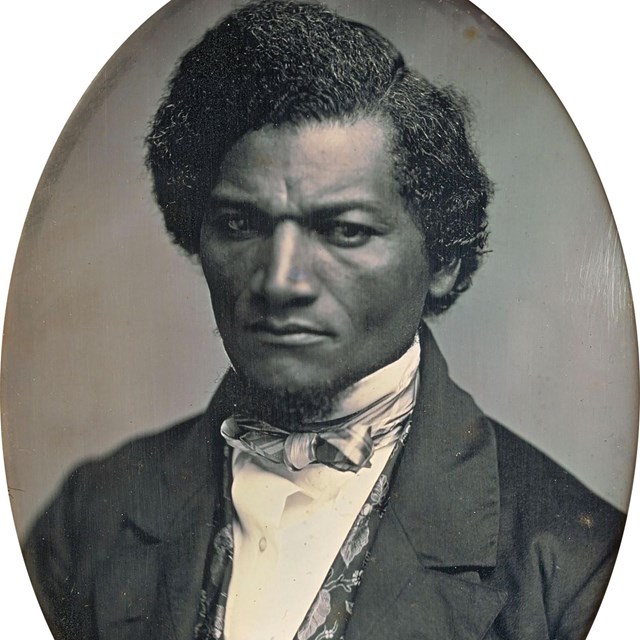

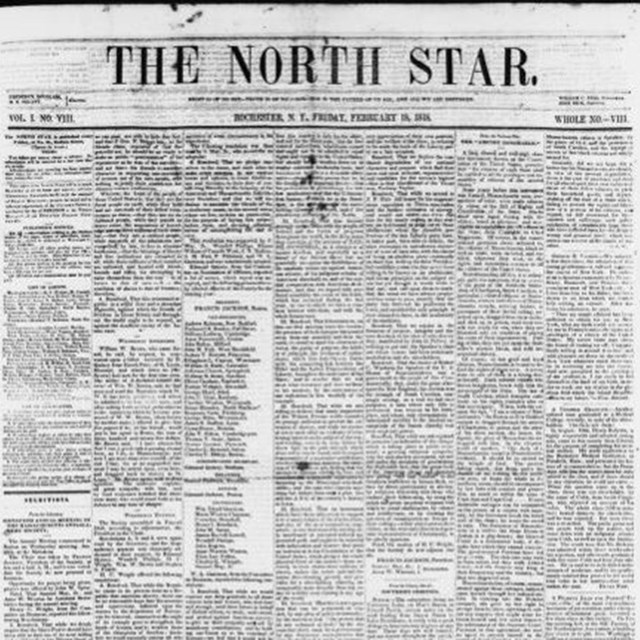

R: The convention stuck with someone else that day. Here is the report from Frederick Douglas -- who owned the North Star Printing Office in nearby Rochester.

A Convention to discuss the SOCIAL, CIVIL, AND RELIGIOUS CONDITION OF WOMAN, was called by the Women of Seneca County, N.Y., and held at the village of Seneca Falls, in the Wesleyan Chapel, on the 19th and 20th of July, 1848.

The question was discussed throughout two entire days: the first day by women exclusively, the second day men participated in the deliberations. LUCRETIA MOTT, of Philadelphia, was the moving spirit of the occasion.

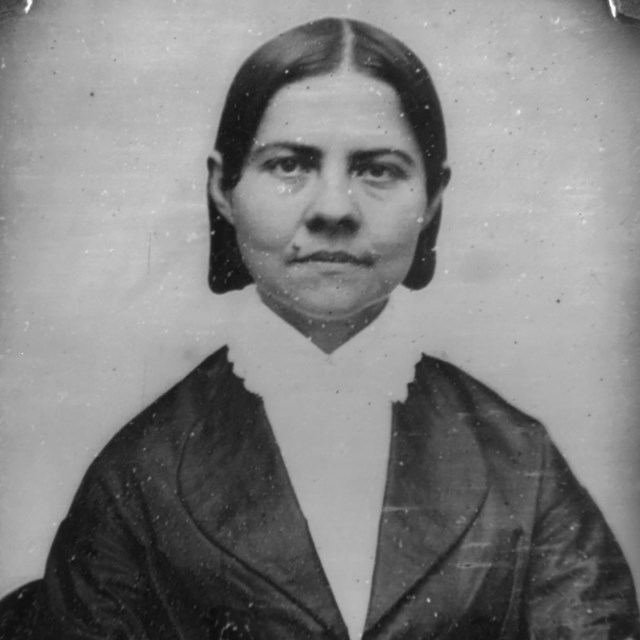

R: So what did they talk about? A whole laundry list, Lisa Tetrault explains. Tetrault: in that declaration of sentiments were a whole list of demands that the women and men at this convention endorsed equal wages, an end to the sexual double standard, women's access to the professions, a woman's right to own property and also the right to vote quite controversially. That was the one thing that didn't pass unanimously. Frederick Douglass, the emerging African-American statesmen, escaped slave and abolitionist, lived up the road in Rochester, New York. So he was there as well. And he gave an impassioned defense of the voting of women. And with that, it ended up passing. But it was the only resolution not passed unanimously. From there, the declaration of sentiments kind of went out into the nation. And a variety of women around the country, mostly in the Midwest and the Northeast, started organizing women's rights conventions. And all of this culminated in 1850 in a national women's rights convention, the first which would have been, advertised well in advance and invited people from around the country in Worcester. It's called the Worcester Convention of 1850. R: That other convention was organized by Lucy Stone. If her name is new to you, you’re not alone. She never made it on a coin. But we’ll hear more about her in a bit.

RD: So back to Seneca Falls, 1848. Here we are at the beginning of the suffrage movement. Tetrault: It was not the beginning of the suffrage movement. R: Doh that’s right Tetrault: that story of Seneca Falls is often used today and in the 19th century to start the beginning of the suffrage movement. It was one of the first calls for the right to vote. One of the great myths about Seneca Falls is that it was the first demand for the suffrage. It was not. And the thing about that story that I became curious about was why do people tell that story when there are so many other things that could be used to anchor a beginning or to anchor multiple beginnings. RD: Seneca Falls was the first convention. But it was not the first time women were organizing and demanding their rights. So where does this legend come from? Tetrault: As I researched where the story came from, not the event itself, which becomes super canonical by the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century. And it actually comes out of a series of political battles in the 1870s and the 1860s that Stanton, who had been at the Seneca Falls convention, Susan B Anthony, her coworker and best friend, and two of the leading suffragists of the nation.

R: Finally we’re getting to Susan B. Anthony. But, before we can understand why Seneca Falls and Susan B Anthony - who wasn’t even there! - become so canonical, we need to back up a bit.

[Music prod note]

RD: The declarations at Seneca Falls were inspirational, but they carried no instructions. Just a few months after the meeting, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote to a friend

“We have declared our right to vote— The question now is how should we get possession of what rightfully belongs to us?”

R: At that time, States controlled who could vote. And their constitutions outlined who was excluded. For example if you wanted to vote in Wisconsin in 1848 you had to be a male, over the age of 21, and be a resident for at least a year before the election.

Then, in 1861, the Civil War began. for the most part, no women had gained the right to vote in any state at that point. In only a couple of states were women able to vote in certain local elections.

But around the country people are talking about equal rights. And they’re talking about the politics of state and federal laws.

R: And when the war was over in 1865, the nature of suffrage had changed. With Reconstruction comes new questions. What does being free mean? What does being a citizen mean? And who will get to decide?

RD: Quick reminder from the last episode. Because I’m sure you - like me - have not memorized the entire constitution.

RD: The 14th amendment was written to establish formerly enslaved people as citizens. But it includes the word male for the first time, which complicates voting rights for women.

R: In 1866 Susan B. Anthony responds to a crowd in New York: “now is the hour not only to demand suffrage for the negro, but for every other human being in the Republic.”

R: Suffragists petitioned Congress to consider Universal suffrage. And in 1868 a Congressman from Indiana introduced an amendment to achieve that. One that would give citizens the right to vote without any distinction founded on race, color or sex.

RD: This forward momentum came to an abrupt end. Congress rejected universal suffrage in favor of suffrage for men, and proposed the Fifteenth amendment.

Tetrault: A whole variety of complicated national politics are going on. Congress decides to endorse black male voting, but not female voting. And they propose Congress does the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, one of the last and final reconstruction amendment. And in that, they say that the states may not discriminate in voting on the basis of race, but they don't say on the basis of sex.

RD: The women’s rights movement lost its fight towards a universal vote for all...for now

RD: And African-American women had to choose between their individual rights and the rights of their male allies.

[music up]

RD: Which brings us to the political battles that Lisa Tetrault talked about. Two groups with rival ambitions formed. One, called the National Woman Suffrage Association, or The National, was formed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

R: And the other, called the American Woman Suffrage Association, was led by Lucy Stone. Remember we said we’d get back to her?

R: Stanton, Anthony and the National wanted to keep pressure on the federal government for universal voting rights for women.

Stone and the American group wanted to take a state by state approach.

R: Some white women would not put the fight for Black men's right to vote ahead of the fight for their own rights. And so, Stanton, Anthony and the National actively campaigned against the 15th amendment, because while it would provide for Black men’s right to vote, it would still exclude women.

Lucy Stone, along with Frederick Douglass and others, would support the 15th amendment as it was written.

RD: But, it’s important to note that Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass were not always on opposing sides. The Rochester neighbors were also close friends. And shared many goals as officers in a group called the American Equal Rights Association.

Their goals were at odds at one meeting in May of 1868, however. Douglass addressed the AERA group saying “You women,” meaning white women, “have representatives. Your brothers, and your husbands, and your fathers vote for you, but the black wife has no husband who can vote for her.” And Douglass himself did have the right to vote in New York when he lived there. And he voted.

Douglass went on to speak to other groups about the dangers that Black Americans would face if they didn’t achieve full protection under the law. And that meant citizenship and voting rights.

“If the elective franchise is not extended to the negro, he dies–he is exterminated”

But these arguments did not win over Anthony. She would not campaign for an amendment that gave rights to men and left women out.

R: And in 1869, there was another meeting for the AERA, again to discuss the 15th amendment. Here’s what happened.

Tetrault: Stanton & Anthony stand up and refuse to support it along with a handful of other people. And most of the people in the room are quite shocked and amazed by this, including Frederick Douglass. And there's a very ugly exchange between Anthony and Douglas and Stanton, particularly between Stanton and Douglass, where Stanton stands up and says, you know, if it's a matter of priority where men, you know, black men go before women, then women should go first. But by this, she clearly means educated white womanhood. And she says, I refuse to support this amendment, ignorant black man, black Sambos, She uses this kind of racist language, should not be allowed to vote. You know, before educated white womanhood, she goes on to rail against immigrants as ignorant, Chinese and Irish immigrants should not be allowed to vote before her. Her elevated white womanhood and Douglass come back, comes back and says, you know, our lives are in danger. We're being hunted down in the streets across the south and we need to vote to save our lives. And Stanton says no. Stanton and Anthony both, remember, Douglass had been the big supporter of women's suffrage, and they refused to support black male suffrage before white women's suffrage. and they formed the first national suffrage organization, the National Women's Suffrage Association, which is dedicated to enfranchising women and not supporting the 15th Amendment. I mean, it's a very ugly chapter. R: It’s an ugly chapter that, for the most part, would not get told in history books. Seneca Falls, however, would. This is Lisa Tetrault’s theory as to why.

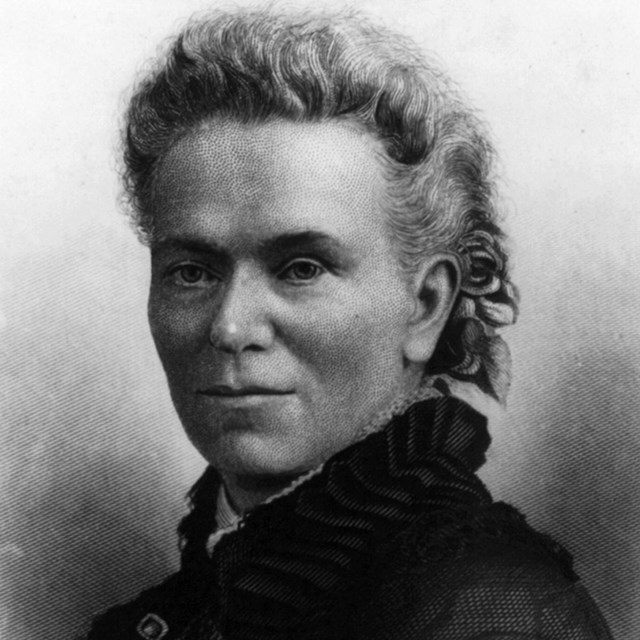

Tetrault: The story of Seneca Falls itself becomes so important moving forward in the movement and so well-known and so widely known. And its two creators and its two central keepers are Stanton and Anthony themselves. And so Anthony starts to become so tightly associated with the story and so tightly associated with Stanton that it starts to seem that she was herself there, even though she wasn't. She will never outright claim to have been there. But she really becomes the keeper of the story in a way that it becomes hers and it then becomes her. R: As Lisa Tetrault tells it, in the 1860s and 70s, Stanton and Anthony’s leadership in the suffrage movement is in danger. And they’re embattled. They're in, how should we put it… Tetrault: in a whole hot mess. R: Ok a whole hot mess. And so looking for good news to share, they start to look backward. Tetrault: they keep positioning themselves as the originators of the movement and thereby the rightful voice of the movement in the present. So that's one of the ways that this myth of Seneca Falls operates. They started to tell and market this story in the 1860s, in the 1870s. And eventually it became a story of the movement. But it really began with some very humble origins with kind of Stanton and Anthony narrating it as the beginning of the movement for political purposes. And they used this story to kind of rescue and build their cause and their leadership. And we forget that the story itself, as a political actor that was used and invented some 40 to 50 years later to serve very political purposes in this very ongoing and deeply embattled movement. RD: In addition to telling a good story, Anthony was interested in images. And she invested in capturing hers. Starting in the 1890s, suffragists established national press committees and hired publicity professionals to distribute Anthony’s portrait. Although leading women of color like Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell also had portraits, they lacked the resources to reach a broad audience.

[music - track 1]

[opportunity for riffing]

Retta: So, Rosario, I feel like I'm learning a whole lot of new things about Susan B. Anthony. I mean, she was cool and all but...yikes. Rosario: Mhm. That's what's so important actually about learning about different figures in history is seeing them as whole people in the context of the time that they're in. She might have made different choices now, but it is according to what she knew and how she was raised in the world, that she and how she envisioned things. It's important to get that perspective and world view so we can better understand how we got here today. Even from people who were progressive, who were trying to champion, who are very heroic and who, you know, as she earns her place in history from the work that she did. But so did a lot of other people. And they deserve to have their credit due as well.

R: It doesn’t always go down easy to learn that our heroes are...complicated people. Lisa Tetrault has been thinking a lot about this.

Tetrault: I think it's important to grapple with those things, not just necessarily fell Anthony, you know, sort of take her down or discard her, it reminds us that we have to be very, very careful about thinking that progressive social movements are either good or bad. I think the other thing we have to grapple with when we think about Anthony is not just the racism, but we also still, I think, approach these political actors, particularly when they're women, with a sense that they must be altruistic and they must be somehow magically wonderful. And, you know, egalitarian and supportive of the sisterhood. Even if we mark that sisterhood as white that's not true either. Anthony was deeply undemocratic in a lot of different ways. She was domineering. She was ambitious. But we're not comfortable remembering her that way. And we’re accepting of that in men. But we're not accepting of that in women still. I think in a lot of ways. So there's all kinds of ways in which we have to remember the complexity, not just of this movement, but also of Anthony. RD: When it comes to this period of history, and our myths and legends, Tetrault and other historians point out that there were many black and white activists who opposed the racism in the movement Tetrault: And that other part of the story, the Lucy Stone part, we almost never tell. And what's interesting is part of that is because of the way Stanton and Anthony marginalized her in their own historical work. So Stanton and Anthony not only invent the story of Seneca Falls, they then go on to author in the course of their lifetime, a history of the movement. It's massive work and it becomes the skeleton for narrating the campaign and it's all centered around their national organization. And they have a line at the end calling Lucy Stone a secessionist. You know that she seceded from them. And that only works when you use Seneca Falls as the beginning than they are the movement. Right. And whoever deviates from them then deviates from the path of history when in fact, Stanton and Anthony were really the ones who, if we want to use this kind of inflammatory post-Civil War language of seceding. And they really were the ones that broke. But there's this whole other movement organized around Lucy Stone. That is where most black women will go if they join the kind of mainstream white movement, they will join the American, not the national. RD: But, even bringing Lucy Stone into the story doesn’t tell the whole tale. Of course there are thousands of women - and men - of color fiercely fighting for the cause, too. Other legends, and lesser known figures - we’ll talk about in Episode 3 and 4.

R: And Lucy Stone? Tetrault: Lucy Stone was largely forgotten after her death and after the passage of the 19th Amendment, and even by the time the 19th Amendment passes in 1920, people will say the movement was begun in 1848 at Seneca Falls by Susan B Anthony. You know, I mean, her obituaries say this. So tightly has that that story undergirded their leadership. And Lucy Stone will be largely forgotten, partly because she didn't attend to the politics of memory. R: We’ll be back in a minute.

// BREAK / SHORTIE //

RD: You’re listening to And Nothing Less. Episode 2...Myths and Legends.

R: And we’re just ticking through some of the biggies of the suffrage movement: the origin story, the iconic -- and complicated -- Susan B. Anthony and now we’re up to this anniversary year itself. 100 years from the year 1920.

RD: The year the 19th amendment was ratified.

R: In other words, the year women got the right to vote. Wagner: No, R & RD Together: No? Wagner: no, RD: Here again is Sally Roesch Wagner, author of the anthology The Women’s Suffrage Movement. Wagner: 1920 was not when women first got the vote. Native American women had political voice long before white people entered this land as settlers. RD: And many suffragists were aware of this. Women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a fellow women’s rights activist named Matlida Joslyn Gage were interested in the matrilineal culture of the Native nations in their region in upstate New York.

RD: In those Haudenosaunee tribes, women were responsible for growing and distributing the food. They also made the decisions about whether or not to go to war. And if families separated, children stayed with their mother’s family, as did property.

R: “Never was justice more perfect; never was civilization higher,” Gage wrote about the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy.

R: Suffragists also knew their history, says Wagner. They understood that some women had the right to vote in the U.S. colonies. Wagner: In the colonies vote was determined by whether or not you had property. And if women had sufficient property, they voted in some of the colonies. So when the suffragists were organizing in the National Women's Suffrage Association, for example, Matilda Jocelyn Gage, who is one of the leaders, said we're not asking for a new right. We're asking for the restitution of a right that our foremothers had. They knew women voted in the colonies. R: : For example in New Jersey, some women could vote between 1776 and 1807 before the right was restricted to white males.

[music flourish / end]

RD: Here we are in episode two, and we’ve been talking a lot about voting.

R: Well this is a podcast about suffrage and the 19th amendment. That only makes sense.

RD: True, but that actually brings us to another myth about this history. It was not just about the vote.

To understand the women’s movement of the 18th and early 19th century, Sally Roesch Wagner asks us to think about how diverse the women’s movement of today is. Wagner: if somebody wrote our history and said, well, from nineteen seventy to twenty twenty, the entire focus of the women's movement was the Equal Rights Amendment. It would be as wrong as it is to say that the movement in the 19th century was only the vote. They raised everything from violence against women, equal pay for equal work, there was a dress reform movement. Women having control of their birthing experience pretty much mirrored what we continue to do because we haven't won those any of those battles yet. RD: So now we come to our final myth. And again it’s one that places us at this anniversary year - 1920 - and the reason we’re celebrating [fanfare]: everybody votes!

R: You get a vote (Oprah style)

RD: And you get a vote

R: And even you, over there, you get a vote!

RD: Actually...the 19th amendment does not give women the right to vote.

R: you should probably say that again.

RD: The 19th amendment does not give women the right to vote!

R: I know, it takes a minute. Here, let Lisa Tetrault explain.

Tetrault: One of the great misnomers about the 19th Amendment is that it lets women into a constitutional right to vote. There is no constitutional right to vote, and it only lets some women in. So the 19th Amendment says to the states who are actually the people who control voting in the United States, the federal government does not control who voters are. It's rare in that regard. States do. So the 19th Amendment says to the states, it's one of the few times the feds say to the states who you can and can't vote. You may not discriminate on the basis of sex. So what happens is that where states require voters be male, that word gets struck down and that helps all women because that word was barring all women from voting where it existed. The thing is, it's not sufficient to help all women because many women are still ensnared in other restrictions that the states have. It was a privilege for white women often because they didn't have any other restrictions in their way. So the 19th Amendment enfranchised them indirectly. But many women of color in the South still faced poll taxes or many Latinx women in New Mexico still faced literacy tests, or many immigrants in New York faced literacy tests. So there would've been other things at the state level that would've barred them. But the 19th amendment helped all women. It just wasn't sufficient to help all women. R: So as Lisa and other historians explain it, women didn’t start voting with the 19th Amendment, nor does the 19th Amendment ensure access to the ballot for all women. Tetrault: it still allows discrimination and voting on any other grounds. And this centennial gives us an opportunity to revisit the health of our democracy and ask ourselves what have we won and what do we still need to fight for? [music up] RD: Questions we’ll ask on the next episode of And Nothing Less. I’m Rosario Dawson.

R: And I’m Retta. Talk to you next time.

[Retta CREDITS]

This was And Nothing Less, from the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission, the national parks service and PRX. This podcast was envisioned by W-S-C-C Executive Director Anna Laymon with support from Kelsey Millay.

The production team is Executive Producer Genevieve Sponsler, Producer & Audio Engineer Samantha Gattsek, and Writer & Producer Robin Linn. Our music is by Erica Huang.

The historical content used to create these stories was brought to you by the National Park Service -- teachers can download companion lesson plans at go dot N-P-S dot gov slash suffrage podcast.

For even more suffrage history, visit the Women's Suffrage Centennial Commission at womensvote100 dot org.

[PRX AUDIO SIGNATURE]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage PlacesWomen's Rights National Historical Park

PlacesWomen's Rights National Historical Park Frederick Douglass NHP

Frederick Douglass NHP Susan B. Anthony House

Susan B. Anthony House Susan B. Anthony Headstone

Susan B. Anthony Headstone Replica of the Hiawatha Wampum Belt

Replica of the Hiawatha Wampum Belt Declaration of Sentiments Tea Table

Declaration of Sentiments Tea Table Declaration of Sentiments

Declaration of Sentiments The North Star

The North Star Strategies and ConflictsFlexing Feminine Muscles

Strategies and ConflictsFlexing Feminine Muscles Voting Before the 19th: New Jersey

Voting Before the 19th: New Jersey African American Women and the 19th

African American Women and the 19th ReadingsThe 15th and 19th Amendments

ReadingsThe 15th and 19th Amendments