Part of a series of articles titled The 19th Amendment and Women's Access to the Vote Across America.

Article

Flexing Feminine Muscles: Strategies and Conflicts in the Suffrage Movement

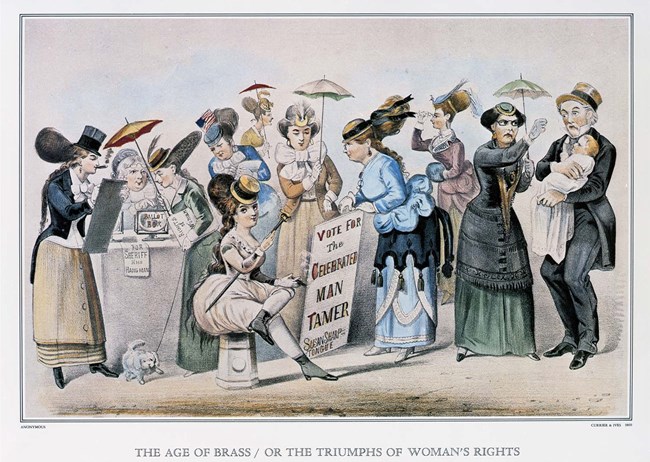

Winning women’s right to vote took the energies of three generations of women, the support of a few men, and nearly a century to accomplish. The process necessitated that suffragists ally with groups holding other priorities—abolitionists, temperance and maternalist reformers, and eventually political and third-party reformers—in their effort to broaden support. When they began in the early nineteenth century, suffragists argued from a natural rights perspective; after the Civil War, during Reconstruction, suffragists cited the importance of women’s unique characteristics as justification for the vote while also demanding the vote for themselves as citizens. Then, as suffragists observed the success of women’s enfranchisement in the West, they increasingly focused on justice and equality arguments. Meanwhile southerners’ tightening of Jim Crow legal restrictions, which constrained African American voting and other rights, led some suffragists to develop arguments that played upon racial fears. Over the course of the movement, suffragists continually modified their strategies, relying on state and national conventions, parlor meetings, petitions, promotional stunts, and print culture. Conflict, inherent to all social justice movements, stimulated ever greater creativity and influenced the strategies women drew upon. By the first two decades of the twentieth century, suffragists had become experts at marketing their movement, overcoming most conflicts with careful strategizing. (Figure 1)

A century earlier, during an era of “parlor politics,” women sought to influence powerful men in private settings. A few daring women, such as Fanny Wright, spoke on lecture circuits and published their ideas. In these early years of the movement, suffragists looked back to the American Revolution to ground their idea that women were citizens and had the same natural rights as men. Because the government derived from the “consent of the governed,” as stated in the Declaration of Independence, women must be included in the electorate. The cry “no taxation without representation” applied to women as well as men. Democratic ideals of equality between races, as well as the growing abolition movement, also influenced ideas related to gender equality. Wright, a freethinker, demanded that women be given an education equal to that of men; African American abolitionist Maria W. Stewart argued for the need to educate young women of color; abolitionists and women’s rights activists Sarah and Angelina Grimké, who spoke to mixed audiences, and Margaret Fuller, author of Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845), called for equality between women and men. By 1846, six property-owning women submitted a petition to the New York State Constitutional Convention demanding it confer upon women the same “equal, and civil and political rights” white men enjoyed.[1] Two years later, in July 1848, five women, including Quakers Lucretia Mott, her sister Martha Coffin Wright, Jane Hunt, and Mary M’Clintock, along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, organized a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Three hundred women and men responded to the call and traveled from across the state to discuss the “social, civil and religious condition and rights of woman.”[2] The organizers drafted a Declaration of Sentiments—based on the wording of the Declaration of Independence—and called for greater civic and political rights for women.

During two days of debate, attendees supported most of the Declaration’s resolutions. Mott had forewarned Stanton that a demand for women’s enfranchisement would likely put other goals of the convention at risk. As predicted, activists argued strenuously over inclusion of a demand for woman suffrage. Frederick Douglass and a few others finally convinced those in attendance to support the resolution—although they expected “misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule.” They determined to circulate tracts, petition legislators, curry the support of religious leaders and the press, and travel the speaking circuits. Immediately planning for additional conventions, activists eventually expected to hold them nationwide.[3] For a dozen years, women’s rights conventions drew the curious and the interested.

At war’s end, the link between women’s rights and rights for freed people remained, shaping postwar strategies and conflicts. At the 1866 national women’s rights convention, the first since before the war, white and Black reformers founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) to secure suffrage “irrespective of race, color, or sex.” Lucretia Mott, known for her commitment to equal rights and her ability to mediate between opposing factions, served as president.[6] Association members traveled the lecture circuit, even influencing some southern states to consider equal rights.[7] However, when, with the Fourteenth Amendment, legislators tied representation in Congress to the number of male voters, suffragists divided over their loyalties.[8] By the 1869 AERA convention, during congressional debates on the Fifteenth Amendment to enfranchise Black men, Douglass, Stanton, Anthony, and Massachusetts suffrage leaders Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell argued vehemently. Stone reasoned that enfranchisement for Black men signified progress, while Stanton and Anthony contended that woman suffrage was equally important and should not be sacrificed. The AERA underwent a painful split.[9]

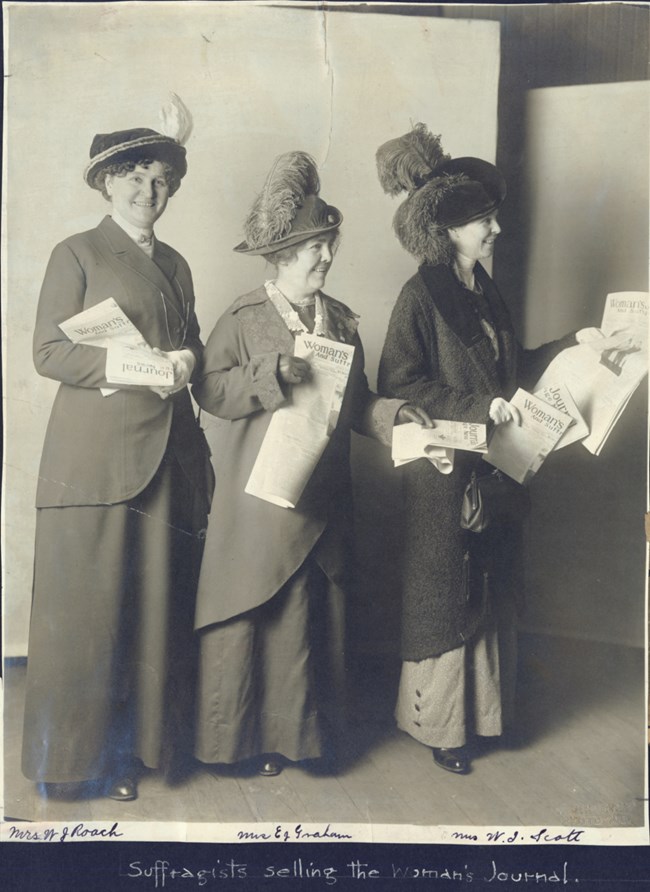

Two new organizations resulted that grew in strength and political expertise as their leadership developed increasingly effective ways to promote woman suffrage. Anthony and Stanton immediately established the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) with an all-female membership, demanding a sixteenth amendment enfranchising citizens without regard to sex. Their weekly newspaper, the Revolution, publicized their views on woman suffrage, politics, labor, and other subjects.[10] By September, rivals Stone and Blackwell founded the less militant American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).[11] Its members, which included women and men, focused on state campaigns to demand or expand woman suffrage, staying away from other issues. Stone also began the Woman’s Journal in 1870, which became the most successful and longest lasting suffrage newspaper. (Figure 2) Whether states or the federal government should dictate who had the right to vote remained a contentious issue throughout the movement.

Black women activists divided their allegiance between the AWSA and the NWSA. Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman attended NWSA conventions, while Charlotte Forten and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper supported the AWSA.[12] Although most Black women’s benevolent and literary clubs supported suffrage for women, Sarah Smith Thompson Garnett founded the first known organization of Black women devoted specifically to suffrage, the Brooklyn Colored Woman’s Equal Suffrage League, in the late 1880s.[13] African American suffragists operated in dynamic networks of support in Black communities in cities throughout the nation but tended to work outside the mainstream movement, in part because white women, particularly in the South, rarely welcomed their Black sisters.[14]

Suffragists employed ever more complex strategies to promote women’s enfranchisement. Suffrage leaders formulated a legal strategy they called the “new departure,” which argued that voting was one of the “privileges or immunities” of citizenship protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. From 1868 to 1872, hundreds of Black and white women suffragists registered and voted, hoping to bring the issue before the courts. Officials arrested many of these women, who then filed suit—or were charged with a crime. Sojourner Truth, Sarah Grimke, her niece Angelina Grimke Weld, Matilda Joslyn Gage, and many other less well-known women engaged in this strategy. The most famous of these was Susan B. Anthony, who, along with fourteen other women, voted in an 1872 election in Rochester, New York.[15] Her trial resulted in a guilty verdict and a fine she refused to pay.[16] Virginia Minor of Missouri further tested the understanding of citizenship as plaintiff in Minor v. Happersett in the 1874 United States Supreme Court. Justices unanimously determined that the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend that woman suffrage be guaranteed. The case marked a serious setback not just for the woman suffrage movement, but for civil rights of all citizens, and refocused attention on a federal amendment.[17]

After years of hard work, in 1887 members of the NWSA and legislative supporters finally brought a proposal for a federal amendment to a vote in Congress. It failed, prompting suffragists to revise their strategies yet again, beginning with uniting disparate suffrage factions. Lucy Stone and her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, began negotiations with Susan B. Anthony to merge the AWSA and the NWSA.[18] The process took more than two years, and many leaders, such as Matilda Joslyn Gage of New York and Olympia Brown of Wisconsin, who feared the loss of attention to a federal amendment, opposed the merger.[19] Nevertheless, the two groups became the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in February 1890.[20] Many state and local political equality and suffrage clubs, once affiliated with one or the other of the former associations, formalized their affiliation with the new association.[21]

Courtesy Carrie Chapman Catt Albums, part of the Carrie Chapman Catt Papers at Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections Department, Bryn Mawr, PA.

In the late nineteenth century, as the country industrialized and urbanized, and as immigration brought increasing diversity, class and ethnic divisions undermined an assumed male equality. White supremacist rule returned to the southern states, increasing racially based violence. Simultaneously, suffragists argued that the nation would benefit from women’s selflessness, devotion to family, and social benevolence. Some women, especially those who also supported temperance, claimed they needed the ballot for self-protection or to meet social reform goals. Many elite, white suffragists advocated for restricted suffrage, promoting the idea of enfranchising educated white women but not the “undesirable” classes (immigrants and Blacks) as a solution.[25] So, while many women had come to support suffrage, they sometimes did so from dramatically different perspectives.

As the United States expanded westward, new territories and states entered the union, often with women entitled to the vote. Strategies women in the West utilized mirrored those used in the East, including lobbying, participating in parades and meetings, supporting the party that endorsed woman suffrage, forming coalitions, and increasing the respectability of women’s voting.[26] Campaigns in the West also benefited from eastern women who traveled west to organize suffrage support. Organizations sent observers to the West to determine the success or failure of women’s enfranchisement, putting to rest some of the arguments that claimed disaster if women regularly went to the polls. Although the population of the western states was small, they represented a steadily growing number of women voters. With women holding increasing political power, state and federal legislatures paid more attention to women’s demands.

As more women attended college, they increasingly sought professions in the public sphere. Oberlin College in Ohio had opened its doors to Black men in 1835 and women in 1837, but for a long time it remained rare for either group to complete college degrees. New colleges, such as Vassar (1861), Wellesley (1881), and Bryn Mawr (1885) opened as women’s institutions.[27] Even as critics of woman suffrage advocated for “true womanhood,” the ideology based on women’s role in the domestic sphere, people supported higher education for women.[28] But when the 1900 federal census showed that the birth rate had dropped while immigrant women continued to have large families, some, including Theodore Roosevelt, argued that educated women who shirked their “duty” to procreate engaged in “race suicide.”[29] Nevertheless, the ultimate success of suffrage would depend on the involvement and support of women (and men) of all of races, ethnicities, and classes.

Though observers increasingly realized the illogic of the dire predictions of social disruption once expected of woman suffrage, some women actively resisted enfranchisement. Women opposed to woman suffrage published articles in lady’s magazines; others frustrated suffragists by their indifference.[30] However, as more prominent people announced their support for suffrage, it prompted those who opposed it to acknowledge the need to organize. In 1890 a Massachusetts anti-suffrage organization began the journal Remonstrance to publicize the dangers of women in politics.[31] The anti-suffrage Woman’s Protest, which eventually became the Woman Patriot, began in 1912 and continued until 1932.[32]

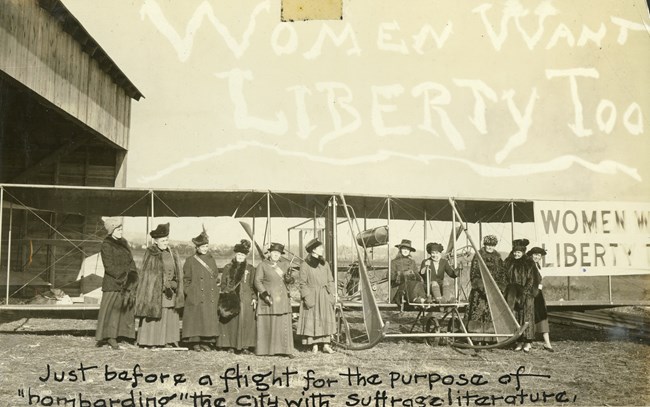

Courtesy Carrie Chapman Catt Albums, part of the Carrie Chapman Catt Papers at Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

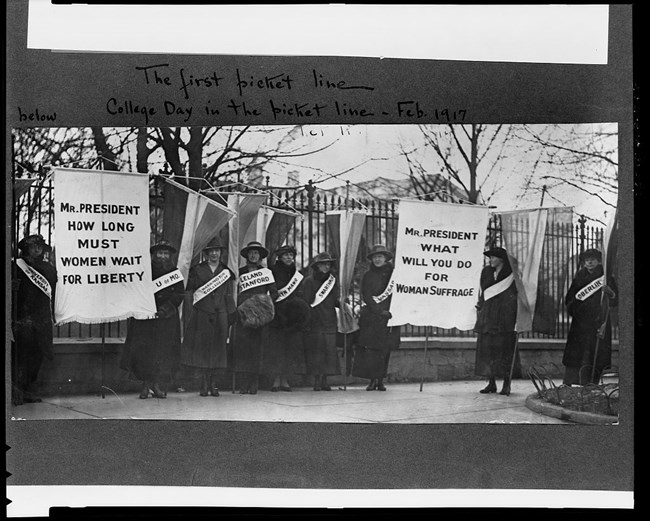

Suffragists established ever more sophisticated patterns of organization to reach voters, especially in advance of a referendum, a question posed by legislators to the voters to decide if women could vote. Suffragists had success with referenda in Nebraska (1882), Colorado (1893), and California (1896). They also used telephones and telegraphs, marched in parades wearing clothing that evoked ideas of women as feminine and pure, and appropriated modern marketing techniques.[35] Influenced by consumer capitalism, suffragists designed and distributed buttons, pennants, ribbons, calendars, sheet music, fans, playing cards, toys, dolls, china dishes, and other souvenirs.[36] They mailed thousands of postcards, and they used yellow, a common suffrage color, for letters and promotional literature.[37] Suffragists spoke on street corners, organized motorcades and hikes, and held beautiful baby contests. (Figure 3) They showed the electorate that women could be beautiful and domestic as they carried out their political duties. Suffragists staged mock daring feats, such as rescuing an anti-suffragist who fell into the sea, or piloted planes while they scattered suffrage literature.[38] (Figure 4) When the Titanic sank in 1912, suffragists, referring to rumors of men who wore women’s coats to slip onto lifeboats, declared that women could not depend on men to protect them.[39] Anything that happened became fodder for suffrage publicity.

Having learned from the Civil War experience, suffragists knew better than to set aside their reform vision when the nation entered World War I. They used their political expertise to promote war preparedness and patriotism, sell Liberty Bonds, offer Red Cross service, and gather information for the government.[40] Others, however, refused to do war work, since their government denied them political equality; peace activists opposed war entirely. Members of NAWSA, like Progressives and socialists, saw opportunities to demonstrate women’s importance to the state in war work. Anti-suffragists, on the other hand, almost to a woman, devoted themselves to patriotic service and asked suffragists to put the campaign on hold.[41] Both suffragists and anti-suffragists portrayed themselves as ideal citizens, since citizenship required service to the state.

By the end of 1912, suffrage strategies changed again, influenced by Alice Paul’s involvement in NAWSA. and Lucy Burns’s involvement in NAWSA. Paul, inspired by her work with the radical branch of the British movement, became frustrated with what she saw as the stagnation of the US movement. Deeming the strategy of state-by-state campaigns ineffective, she and Lucy Burns took over NAWSA’s Congressional Committee and focused on obtaining a federal amendment. As its first major event, the Congressional Committee held an enormous pageant and march on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Fifty African American women marched in the parade despite NAWSA leadership's attempt to marginalize them.[42] The pageant drew national attention and, because many of the marchers suffered taunts and physical abuse from parade watchers, public sympathy. However, Catt accused Paul and Burns of defying the national leadership in their organizing and fundraising efforts, especially after they formed a concurrent affiliate group called the Congressional Union (CU). Paul and Burns soon left NAWSA and the Congressional Committee and ran the CU independently. The union, headquartered in Washington, DC, held daily meetings, established branches in different states, and published the Suffragist, featuring articles by prominent authors. In 1916, the Congressional Union established the National Woman’s Party.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

During these same years, NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt implemented her “winning plan,” advocating for state enfranchisement as well as a federal amendment. By 1917 women had won the vote in eleven western states.[44] After New York voters approved a woman suffrage referendum, suffragists shifted their focus to Congress and a federal constitutional amendment. Persuaded by suffrage arguments, some congressmen claimed that enfranchising women should be a war measure, and Wilson, surely moved by the determination of the militant suffragists, increased suffrage agitation, and widening support from politicians, finally declared he would back a federal amendment. It still took several votes, however, before both the House of Representatives and the Senate passed the measure.

Once passed, the amendment required ratification by at least thirty-six states, and suffragists and anti-suffragists campaigned vigorously. They gathered wherever a state legislature convened to debate the amendment, speaking directly with legislators. They sent a flurry of telegrams to press their views, and each side kept a tally of states as legislatures voted on the amendment. Tennessee (“Armageddon,” to suffragists) became the last state to ratify the amendment and did so by a single vote. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed the certificate of ratification for the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution on August 26, 1920, with no suffragists present.[45]

The suffrage movement represents an extraordinary effort on the part of women to change not only their role in the polity, but also the perception of women as engaged civic-minded citizens. Never again would women, as a class of citizens, be content with lives defined by domesticity. Although the process had been long and complicated, and the movement steeped in conflict and controversy, suffragists used ever more effective strategies that ultimately won them the right to full political participation.

Susan Goodier teaches at SUNY Oneonta and studies US women’s activism, particularly woman suffrage activism. She is coordinator for the Upstate New York Women’s History Organization and recently edited a double issue on New York State women’s suffrage for New York History. She is the author of No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement (University of Illinois, 2013) and coauthor of Women Shall Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State (Cornell University Press, 2017). Her current projects include a biography of Louisa M. Jacobs, the daughter of Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl and a history of black women in the New York suffrage movement.

Notes:

[1] Quote is from the text of “1846 Petition for Woman's Suffrage,” reprinted in Jacob Katz Cogan and Lori D. Ginzberg, “1846 Petition for Woman's Suffrage, New York State Constitutional Convention,” Signs 22, no. 2 (Winter 1997): 438–39. See also Lori D. Ginzberg, Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 7.

[2] North Star, July 14, 1848, 2.

[3] Lisa Tetrault, The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014). Full text of the women’s rights convention can be found at Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project.

[4] Sally G. McMillen, Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 149.

[5] Judith Ann Giesberg, Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women’s Politics in Transition (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000), 105–107.

[6] Proceedings of the First Anniversary of the American Equal Rights Association, Held at the Church of the Puritans, New York, May 9 and 10 (New York: Robert J. Johnston, Printer, 1867).

[7] Laura E. Free, Suffrage Reconstructed: Gender, Race, and Voting Rights in the Civil War Era (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 149.

[8] Ellen Carol DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848–1869 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978), 63-64, 68.

[9] Tetrault, Myth of Seneca Falls, 7–8, 16; DuBois Feminism and Suffrage; and Ellen Carol DuBois, “Outgrowing the Compact of the Fathers: Equal Rights, Woman Suffrage, and the United States Constitution, 1820–1878,” Journal of American History 74, no. 3 (December 1987): 836–862, helps to decenter the Stanton-centric story while also describing strategies.

[10] McMillen, Seneca Falls, 171–172.

[11] When Stanton, Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage compiled the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, Stone refused to submit her biography or an essay about the American Woman Suffrage Association. Harriot Stanton Blatch wrote it and tried to do justice to the organization. However, historians since have focused less attention on the Boston-based organization, distorting our understanding of the nineteenth-century woman suffrage movement. Ellen Carol DuBois, Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 49–50.

[12] Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 42.

[13] See New York Heritage Digital Collections for images and documents related to the Colored Woman’s Equal Suffrage League.

[14]Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1–3; Susan Goodier and Karen Pastorello, Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017), 75.

[15] For a complete list of the women who voted, see Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project.

[16] For a full account of the trial, see N. E. H. Hull, The Woman Who Dared to Vote: The Trial of Susan B. Anthony (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012), chap. 6.

[17] Norma Basch, “Reconstructing Female Citizenship: Minor v. Happersett,” in The Constitution, Law, and American Life: Critical Aspects of the Nineteenth-Century Experience, ed. Donald G. Nieman (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992), 52, 55, 61.

[18] Suzanne M. Marilley, Woman Suffrage and the Origins of Liberal Feminism in the United States, 1820–1920 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 82; Tetrault, Myth of Seneca Falls, 155.

[19] Charlotte Coté, Olympia Brown: The Battle for Equality (Racine, WI: Mother Courage Press, 1988), 130–32; Goodier and Pastorello, Women Will Vote, 21.

[20] Tetrault, Myth of Seneca Falls, 156.

[21] For example, see Goodier and Pastorello, Women Will Vote, 22.

[22] Sara Hunter Graham, Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 8.

[24] Trisha Franzen, Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014), 7, 109.

[25] Aileen S. Kraditor, The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890–1920 (1965; New York: W. W. Norton, 1981), 43, 45–46, 52–54, 72.

[26] Rebecca Mead, How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914 (New York: New York University Press, 2004), 2, 53, 67, 71.

[27] Ann D. Gordon et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, vol. 1, In the School of Anti-Slavery, 1840 to 1866 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 98.

[28] Sarah B. Cooper, “Woman Suffrage—Cui Bono?,” Overland Monthly 8, no. 2 (February 1872): 163.

[29] Jean V. Matthews, The Rise of the New Woman: The Women’s Movement in America, 1875–1930 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003), 38.

[30] There are many examples of statements like this. See, for example, Cooper, “Woman Suffrage—Cui Bono?,” 157–158.

[31] Susan E. Marshall, Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign against Woman Suffrage (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 24–25.

[32] Goodier, No Votes for Women, 193n2.

[33] Matthews, Rise of the New Woman, 127. See also DuBois, Harriot Stanton Blatch.

[34] Goodier and Pastorello, Women Will Vote, 172–173.

[35] See Mead, How the Vote Was Won.

[36] The best suffrage ephemera websites include Kenneth Florey’s Woman Suffrage Memorabilia; “Women’s Suffrage Ephemera Collection,” Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections; the “National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection” at the Library of Congress; and “Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party” at the Library of Congress. See also “Recognizing Women’s Right to Vote in New York State,” New York Heritage Digital Collections.

[37] Kenneth Florey, “Postcards and the New York Suffrage Movement,” New York History 98, no. 3–4 (Summer/Fall 2017): 441–442.

[38] Goodier and Pastorello, Women Will Vote, chap. 6.

[39] Steven Biel, Down with the Old Canoe: A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996), 8, 10, 23.

[40] Barbara J. Steinson, American Women’s Activism in World War I (New York: Garland, 1982), 174.

[41] Susan Goodier, No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 93–95.

[42]J. D. Zahniser and Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 126–150.

[43] Zahniser and Fry, Alice Paul, 255–260; Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1920), appendix 4, 354–371.

[44] Goodier and Pastorello, Women Will Vote, 160, 168, 191.

[45] Zahniser and Fry, Alice Paul, 299–304, 314–316, 319; “Suffrage Proclaimed by Colby, Who Signs at Home Early in Day,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 26, 1920, 1–2.

Bibliography

Baker, Jean H., ed. Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Baker, Paula. “The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780–1920.” American Historical Review 89, no. 3 (June 1984): 620–647.

Blatch, Harriot Stanton, and Alma Lutz. Challenging Years: The Memoirs of Harriot Stanton Blatch. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1940.

Boland, Sue. “Matilda Joslyn Gage.” In American Radical and Reform Writers, 2nd ser., edited by Hester Lee Furey, 141–154. New York: Gale Cengage Learning, 2009.

Camhi, Jane Jerome. Woman against Woman: American Anti-Suffragism, 1880–1920. Brooklyn: Carlson Publishing, 1994.

Catt, Carrie Chapman, and Nettie Rogers Shuler. Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926.

Chapman, Mary. Making Noise, Making News: Suffrage Print Culture and U.S. Modernism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Cooney, Robert P. J., Jr. Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement. Santa Cruz, CA: American Graphic Press, 2005.

Cott, Nancy F. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Coté, Charlotte. Olympia Brown: The Battle for Equality. Racine, WI: Mother Courage Press, 1988.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848–1869. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Finnegan, Margaret. Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture & Votes for Women. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Flexner, Eleanor, and Ellen Fitzpatrick. Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States. 1959. Enlarged ed., Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1996.

Florey, Kenneth. Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2013.

Franzen, Trisha. Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Free, Laura E. Suffrage Reconstructed: Gender, Race, and Voting Rights in the Civil Rights Era. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Giesberg, Judith Ann. Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women’s Politics in Transition. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Goodier, Susan. No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Goodier, Susan, and Karen Pastorello. Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Gordon, Ann D. et al., eds. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. 6 vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997–2013.

Graham, Sara Hunter. Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

Gustafson, Melanie, Kristie Miller, and Elisabeth I. Perry, eds. We Have Come to Stay: American Women and Political Parties, 1880–1960. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Gustafson, Melanie Susan. Women and the Republican Party, 1854–1924. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Harper, Ida Husted. The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony. Vols. 1–2. Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1898.

Hull, N. E. H. The Woman Who Dared to Vote: The Trial of Susan B. Anthony. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012.

Jablonsky, Thomas J. The Home, Heaven, and Mother Party: Female Anti-Suffragists in the United States, 1868–1920. New York: Carlson Publishers, 1994.

Kimmel, Michael S., and Thomas E. Mosmiller, eds., Against the Tide: Pro-Feminist Men in the United States, 1776–1990. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.

Kraditor, Aileen S. The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890–1920. 1965. New York: W. W. Norton, 1981.

Lumsden, Linda J. Rampant Women: Suffragists and the Right of Assembly. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997.

Lunardini, Christine. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910–1928. San Jose, CA: toExcel Press, 2000.

Marilley, Suzanne M. Woman Suffrage and the Origins of Liberal Feminism in the United States, 1820–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Marshall, Susan E. Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign against Woman Suffrage. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Matthews, Jean V. The Rise of the New Woman: The Women’s Movement in America, 1875–1930. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003.

McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Mead, Rebecca. How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

National American Woman Suffrage Association. Victory: How Women Won It, a Centennial Symposium, 1840–1940. New York: H. W. Wilson Company, 1940.

Penney, Sherry H., and James D. Livingston. A Very Dangerous Woman: Martha Wright and Women’s Rights. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady et. al, eds. The History of Woman Suffrage. 6 vols. Rochester, NY: S. B. Anthony; New York: National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1881–1922.

Steinson, Barbara J. American Women’s Activism in World War I. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Vacca, Carolyn S. A Reform against Nature: Woman Suffrage and the Rethinking of American Citizenship, 1840–1920. New York: Peter Lang, 2004.

Van Voris, Jacqueline. Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1987.

Venet, Wendy Hamand. Neither Ballots nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991.

Wagner, Sally Roesch. Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee Influence on Early American Feminists. Summertown, TN: Native Voices Book Publishing Company, 2001.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill. One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. Troutdale, OR: New Sage Press, 1995.

Zaeske, Susan. Signatures of Citizenship: Petitioning, Antislavery, and Women’s Political Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Zahniser, J. D., and Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Baker, Jean H., ed. Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Baker, Paula. “The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780–1920.” American Historical Review 89, no. 3 (June 1984): 620–647.

Blatch, Harriot Stanton, and Alma Lutz. Challenging Years: The Memoirs of Harriot Stanton Blatch. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1940.

Boland, Sue. “Matilda Joslyn Gage.” In American Radical and Reform Writers, 2nd ser., edited by Hester Lee Furey, 141–154. New York: Gale Cengage Learning, 2009.

Camhi, Jane Jerome. Woman against Woman: American Anti-Suffragism, 1880–1920. Brooklyn: Carlson Publishing, 1994.

Catt, Carrie Chapman, and Nettie Rogers Shuler. Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926.

Chapman, Mary. Making Noise, Making News: Suffrage Print Culture and U.S. Modernism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Cooney, Robert P. J., Jr. Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement. Santa Cruz, CA: American Graphic Press, 2005.

Cott, Nancy F. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Coté, Charlotte. Olympia Brown: The Battle for Equality. Racine, WI: Mother Courage Press, 1988.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848–1869. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Finnegan, Margaret. Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture & Votes for Women. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Flexner, Eleanor, and Ellen Fitzpatrick. Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States. 1959. Enlarged ed., Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1996.

Florey, Kenneth. Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2013.

Franzen, Trisha. Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Free, Laura E. Suffrage Reconstructed: Gender, Race, and Voting Rights in the Civil Rights Era. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Giesberg, Judith Ann. Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women’s Politics in Transition. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000.

Ginzberg, Lori D. Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Goodier, Susan. No Votes for Women: The New York State Anti-Suffrage Movement. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Goodier, Susan, and Karen Pastorello. Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Gordon, Ann D. et al., eds. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. 6 vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997–2013.

Graham, Sara Hunter. Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

Gustafson, Melanie, Kristie Miller, and Elisabeth I. Perry, eds. We Have Come to Stay: American Women and Political Parties, 1880–1960. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Gustafson, Melanie Susan. Women and the Republican Party, 1854–1924. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Harper, Ida Husted. The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony. Vols. 1–2. Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1898.

Hull, N. E. H. The Woman Who Dared to Vote: The Trial of Susan B. Anthony. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012.

Jablonsky, Thomas J. The Home, Heaven, and Mother Party: Female Anti-Suffragists in the United States, 1868–1920. New York: Carlson Publishers, 1994.

Kimmel, Michael S., and Thomas E. Mosmiller, eds., Against the Tide: Pro-Feminist Men in the United States, 1776–1990. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.

Kraditor, Aileen S. The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890–1920. 1965. New York: W. W. Norton, 1981.

Lumsden, Linda J. Rampant Women: Suffragists and the Right of Assembly. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997.

Lunardini, Christine. From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910–1928. San Jose, CA: toExcel Press, 2000.

Marilley, Suzanne M. Woman Suffrage and the Origins of Liberal Feminism in the United States, 1820–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Marshall, Susan E. Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign against Woman Suffrage. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Matthews, Jean V. The Rise of the New Woman: The Women’s Movement in America, 1875–1930. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003.

McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Mead, Rebecca. How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

National American Woman Suffrage Association. Victory: How Women Won It, a Centennial Symposium, 1840–1940. New York: H. W. Wilson Company, 1940.

Penney, Sherry H., and James D. Livingston. A Very Dangerous Woman: Martha Wright and Women’s Rights. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady et. al, eds. The History of Woman Suffrage. 6 vols. Rochester, NY: S. B. Anthony; New York: National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1881–1922.

Steinson, Barbara J. American Women’s Activism in World War I. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848–1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Vacca, Carolyn S. A Reform against Nature: Woman Suffrage and the Rethinking of American Citizenship, 1840–1920. New York: Peter Lang, 2004.

Van Voris, Jacqueline. Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1987.

Venet, Wendy Hamand. Neither Ballots nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991.

Wagner, Sally Roesch. Sisters in Spirit: Haudenosaunee Influence on Early American Feminists. Summertown, TN: Native Voices Book Publishing Company, 2001.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill. One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. Troutdale, OR: New Sage Press, 1995.

Zaeske, Susan. Signatures of Citizenship: Petitioning, Antislavery, and Women’s Political Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Zahniser, J. D., and Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Last updated: January 29, 2020