|

Sitka National Historical Park preserves a culturally significant landscape that communicates stories of the past and present to its visitors. These stories of Tlingit tradition and Russian colonization embed feelings of loss, uncertainty, and hope within the natural surroundings. Sitka also tells a modern story through the Indian River estuary and its spawning salmon, the rain forest’s cedar trees, the coastline, and the present day cultural practices. These are all living representations of Sitka’s history, but today they are at risk from climate change. Threats to these tangible representations, both natural landscapes and the cultural heritage, of the park elicit similar emotions of loss among visitors. What can we do to protect these valuable resources in the face of climate change?

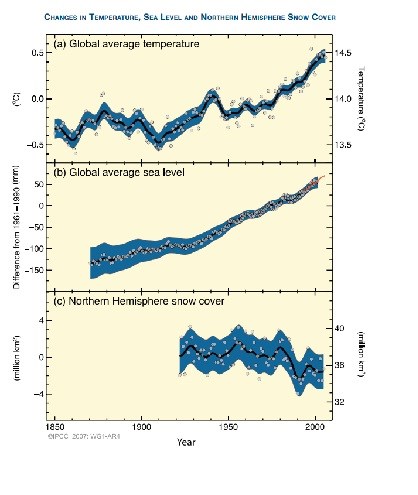

NPS image Over the last 150 years, scientists have observed an increase in global temperature. This is a result of human activities that release heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, for example, is commonly released by burning fossil fuels for transportation, agriculture, and energy. For Sitka, the climate is expected to become warmer and drier over the next century. Learn more about climate change in Alaska and how the climate change in national parks.

IPCC The average annual temperatures in Alaska have increased about 3 degrees Fahrenheit over the last six decades, and the greatest temperature increases were observed during the winter. This small number represents a relatively large change for the coastal rain forest. Southeast Alaska’s temperate environment means that winter temperatures hover around freezing, resulting in enough snow to feed the watersheds in springtime. As temperatures shift to consistently above freezing, this can have dire consequences for an ecosystem that relies on snowpack. Climate change goes beyond global warming and has countless consequences around the world: melting of glaciers and ice, more extreme weather events, changes to oceans and water systems, and more precipitation. How can all these changes be related to one problem? The answer is that each area around the world experiences changes differently depending on year-to-year weather events and regional conditions. Extreme drought in Rocky Mountain National Park can be coupled with flooding in Kenai Fjords National Park because of each region’s vulnerabilities and unique ecosystem. The trend for the future is forecasted to be increased overall warming, made worse if we continue to emit greenhouse gases at the current rate.

National parks are living laboratories that can provide baseline information about original resource conditions and also monitor the long term changes. All park units will continue to be faced with unpredictable and complex issues in the coming decades, posing new threats to preserving their resources. This is the ultimate challenge in addressing climate change: no one person is responsible for threatening the National Parks, but collectively, each of us is contributing to global changes that must be faced together. Disruption for Salmon: An Alaskan Cultural Mainstay

Thousands of pink salmon spawn in Sitka National Historical Park’s Indian River every year. Their presence begins a vital exchange of nutrients for the ecosystem, as their carcasses feed animals and provide natural fertilization for the surrounding forest.

The salmon in and around Sitka have nourished people for thousands of years. Their annual return renews an important connection between the natural world and cultural traditions, an essential connection between people, fish, and forest that has shaped the local way of life. Today, the spawning salmon outnumber residents about 200-to-1. Unfortunately, however, this vulnerable connection is at risk as a result of changes to the surrounding environment.

Salmon are directly threatened by climate change, specifically because of the way climate change may affect the timing of their life cycle. Pink salmon spawn in Sitka’s Indian River, entering freshwater through the park’s estuary (to the same river in which they were born) to produce their own young. This stage of their lifecycle is influenced by the estuary, because salmon arrive to spawn in the river only under certain temperature and flow conditions. Spring snow melt from the surrounding mountains helps to fuel the river’s eight-mile long watershed and maintain its temperature. With warming average temperatures, there is less snow to provide cold water to streams and the timing of snow melt could occur earlier in the season. Snow pack delivers consistent, cold flowing water into rivers that salmon rely on. With less snow melting, the Indian River is predicted to see an increase in temperature and a decrease in stream flow, which will have dramatic consequences for the salmon.

NPS image In the Alaska Maritime region, includeing Sitka, average water temperatures have been increasing. Warm water masses in the Pacific Ocean are linked to a number of changes to the marine ecosystems. We have observed a trend of earlier salmon migration into the rivers. The arrival of salmon into the habitat sooner can cause a mismatch for other organisms that rely on this valuable species as a predator, as a prey, and as a contributor of nutrients. Salmon keep the population of aquatic insects in check and provide food for animals like bears and eagles. As fish carcasses decompose, they fertilize the surrounding soil and allow plants to thrive on marine-derived nutrients. The success of this food web is dependent upon a healthy salmon run, and with a change in timing, the system could easily be altered faster than it can adapt.

Life cycle disruptions and unsuitable conditions for spawning won’t just harm the ecosystem, they also impair the local cultural connection to salmon and economy. Native Southeast Alaskans, like the Tlingit, have been nourished by salmon for thousands of years. Hunter-gatherer societies depended upon the annual return of this important protein, preserving it for winter through smoking and curing. Native peoples in Sitka still depend on salmon for cultural, traditional, and subsistence purposes. Sitka National Historical Park helps preserve this Tlingit history which is fundamentally linked to the natural world. In the face of salmon disruption, both the park and the story of Alaskan Native peoples are being threatened by climate change.

Paul Hennon (USFS) Like salmon, yellow cedar is a natural resource with cultural connections to Alaskan Native peoples. It has traditionally been the preferred wood for carving canoe paddles, masks and bows, and for weaving baskets, mats, and clothing. It has a variety of medicinal purposes and is treated reverently by those who rely on it. Known as culturally modified trees, most were only partially harvested and left standing to continue growing. Sitka National Historical Park helps to preserve the role of this tree within local history by displaying and protecting cultural objects made of cedar. The park’s efforts to memorialize and share the region’s history with visitors are being undermined by climate change, as threats to the natural resources also affect the cultural resources.

In the temperate rain forest of Southeast Alaska, yellow cedar is one of the hardiest and most resourceful trees in the forest. It has evolved shallow roots that can grow in poor soil and natural defensive agents to deter disease and insects. Despite these adaptations, yellow cedar has no protection against climate change which has meant less snow to insulate its delicate root systems. About 500,000 acres of dead yellow cedar are found across Southeast Alaska, far exceeding the tree death of any other species. Yellow cedars have been declining for more than a century, and the number of trees dying each decade increases as the climate warms. These losses are striking; wiping out entire hillsides and compromising the economic value of a forest, the cultural value of a resource, and the inherent value visitors find in the landscape.

The open canopy of an old growth forest allows snow to enter the forest floor and insulate the root systems of yellow cedars. If there isn’t enough snow accumulated, the fatal damage occurs in late winter or spring when exposure leaves the roots vulnerable to freezing. Interestingly, the snow will protect roots rather than endanger them from the cold. A loss of freezing resistance kills the tree from below ground.

Yellow cedar decline is an eye-opening example of climate changes that go beyond a hotter planet. The impacts are cascading from overall warming trends, but increased vulnerability and unpredictability creates loss of all kinds. Visitors to Sitka National Historical Park observe the masterfully crafted Tlingit artifacts and form an appreciation of the yellow cedar, a tree that can be observed dying by the thousands and thereby threatening the current production of art and history itself.

NPS image With climate change threatening some of the region’s most valued cultural symbols Sitka National Historical Park is striving to learn more about how the environment is being altered. Natural resource monitoring has been a key effort in discovering the unpredictable and varied changes that occur within the park.

Long-term water quality monitoring allows researchers to measure factors like pH, temperature, and oxygen within the Indian River. The sensor measures these variables hourly and is one of only three in Southeast Alaska that contributes information for these long-term data sets. The streamflow monitoring program gives valuable information about streamflow in the Indian River. The speed of the river combined with a measure of area can give the park direction in addressing water flow issues for the salmon spawning productivity. Other monitoring programs include intertidal monitoring, bat observations, salmon counts, and freshwater fish contaminant studies. These occur seasonally and help cumulate information for future management decisions.

NPS image There are two primary responses in management action: adaptation and mitigation. Adapting to climate change in Sitka is contingent on the consequences observed, and so far, no direct impacts to visitor experience have been observed. Some future strategies may include adapting management action to participate in active preservation plans for yellow-cedars and salmon, or adapting the operational practices in order to maintain a healthy environment for the resources and visitor experience. In accordance with the Director’s Call to Action, Sitka NHP is working on reducing its overall carbon footprint. The park’s recycling program, an electric transport vehicle, and a fleet of employee bicycles are some examples of the ways in which the park is working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In 2013, the Sitka Global Warming Group recognized Sitka National Historical Park as a “Sitka Green Business." The park’s Green Team continues to strive for the best environmental management practices possible. A commitment to pollution prevention, waste reduction, and energy savings (both fossil fuels and electricity) in park operations are all making a difference in lowering carbon contributions. Despite these positive mitigation efforts, there is much more to be done in reducing Sitka National Historical Park’s contributions to climate change. One huge step forward will be to encourage our visitors to do the same.

How to Help

The national parks are an opportunity to preserve the heritage we all share as Americans, and when under threat, many feel inspired to take action. Individual changes can be as simple as carpooling and using public transit, recycling and composting waste, and making one's home more energy efficient. Carry your own reusable water bottle rather than buying plastic. Eat and buy local products. Ride your bike instead of driving. Purchase carbon-credits to offset carbon emissions, and purchase renewable sources of energy for your home, like wind or solar power. These individual choices can all cumulate in real, significant change.

Action can also mean taking more rigorous steps, like reducing consumption habits, divesting from fossil fuels, purchasing from companies that prioritize the environment, participating in political action, and encouraging those around you to feel a similar urgency. Volunteering at local parks (a city park, state park, or National Park) can help spread the word about climate change to others who value America’s natural spaces.

NPS image For more information about climate change in National Parks, visit: www.nps.gov/climatechange

|

Last updated: February 7, 2019