NPS

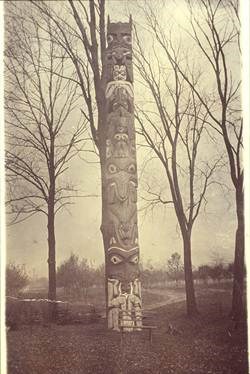

The Milwaukee totem pole, known as the Raven Head Down Pole, is a Tlingit mortuary pole acquired at the Native village of Tuxikan. It was donated to Brady by its owner, a man named Yun-nate who was living at the time at Shakan. The pole was carved in honor of Yun-nate’s mother. Its figures relate to the Raven moiety, the owner’s clan, and to his mother’s uncle who was a noted shaman.

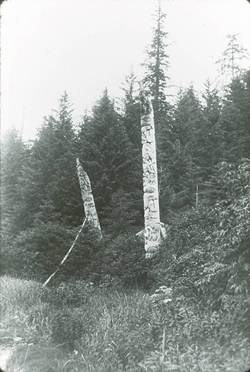

The Golden Hill pole, collected at the old Haida Village of Koiangles (also known as Quinlas or Onhonklis), was donated to Brady by a prominent Haida clan chief named G. Yeltatzie living at the time at Howkan. The pole is a Wasgo (sea monster) family crest totem pole telling the mythological history of the Yeltatzie family. Crest figures include the long snouted sea monster, a bear, and the man in the story along with his mother-in-law with whom he was in conflict.

Recognizing the history of the two missing Brady-collected poles completes the story of the totem poles at Sitka National Historical Park. Although these two poles are separated from the group in Sitka, they are in a sense still very much a part of the celebrated Brady totem pole collection. One may want to complete his or her Sitka experience with a visit sometime to the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis and the Milwaukee Public Museum to see these magnificent examples of monumental Haida and Tlingit art.

By: Richard Feldman, M.D.

|

Last updated: October 28, 2021