| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

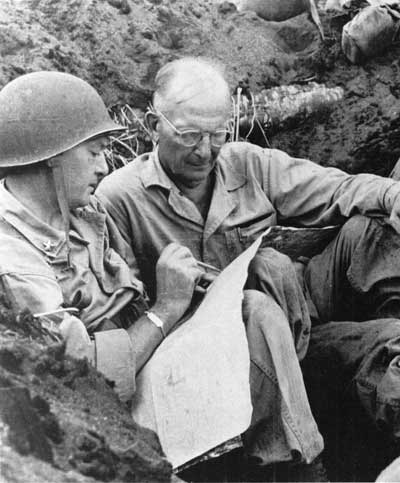

Cape Gloucester: The Green Inferno by Bernard C. Nalty Clearing the Shores of Borgen Bay While General Rupertus personally directed the capture of the air fields, the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., came ashore on D-Day, 26 December, and took command of the beachhead. Besides coordinating the logistics activity there, Shepherd assumed responsibility for expanding the perimeter to the southwest and securing the shores of Borgen Bay. He had a variety of shore party, engineer, transportation, and other service troops to handle the logistics chores. The 3d Battalion of Colonel Selden's 5th Marines—the remaining component of the division reserve—arrived on 30 and 31 December to help the 7th Marines enlarge the beachhead.

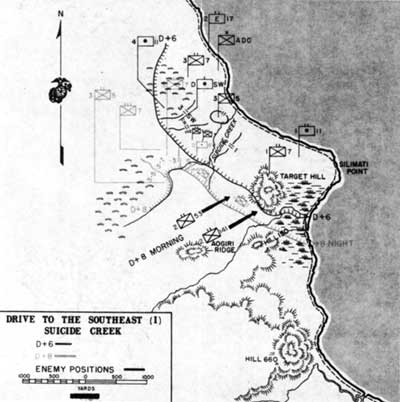

Shepherd had sketchy knowledge of Japanese deployment west and south of the Yellow Beaches. Dense vegetation concealed streams, swamps, and even ridge lines, as well as bunkers and trenches. The progress toward the airfields seemed to indicate Japanese weakness in that area and possible strength in the vicinity of the Yellow Beaches and Borgen Bay. To resolve the uncertainty about the enemy's numbers and intentions, Shepherd issued orders on 1 January 1944 to probe Japanese defenses beginning the following morning. In the meantime, the Japanese defenders, under Colonel Kenshiro Katayama, commander of the 141st Infantry, were preparing for an attack of their own. General Matsuda entrusted three reinforced battalions to Katayama, who intended to hurl them against Target Hill, which he considered the anchor of the beachhead line. Since Matsuda believed that roughly 2,500 Marines were ashore on New Britain, 10 percent of the actual total, Katayama's force seemed strong enough for the job assigned it. Katayama needed time to gather his strength, enabling Shepherd to make the first move, beginning at mid-morning on 2 January to realign his forces. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, stood fast in the vicinity of Target Hill, the 2d Battalion remained in place along a stream already known as Suicide Creek, and the regiment's 3d Battalion began pivoting to face generally south. Meanwhile, the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, pushed into the jungle to come abreast of the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, on the inland flank. As the units pivoted, they had to cross Suicide Creek in order to squeeze out the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, which would become Shepherd's reserve. The change of direction proved extremely difficult in vegetation so thick that, in the words of one Marine: "You'd step from your line, take say ten paces, and turn around to guide on your buddy. And nobody there .... I can tell you, it was a very small war, and a very lonely business." The Japanese defenders, moreover, had dug in south of Suicide Creek, and from these positions they repulsed every attempt to cross the stream that day. A stalemate ensued, as Seabees from Company C, 17th Marines, built a corduroy road through the damp flat behind the Yellow Beaches so that tanks could move forward to punch through the defenses of Suicide Creek.

While the Marine advance stalled at Suicide Creek, awaiting the arrival of tanks, Katayama attacked Target Hill. On the night of 2 January, taking advantage of the darkness, Japanese infantry cut steps in the lower slopes so the troops could climb more easily. Instead of reconnoitering the thinly held lines of Company A, 7th Marines, and trying to infiltrate, the enemy followed a preconceived plan to the letter, advanced up the steps, and at midnight stormed the strongest of the company's defenses. Japanese mortar barrages fired to soften the defenses and screen the approach could not conceal the sound of the troops working their way up the hill, and the Marines were ready. Although the Japanese supporting fire proved generally inaccurate, one round scored a direct hit on a machine-gun position, killing two Marines and wounding the gunner, who kept firing the weapon until someone else could take over. This gun fired some 5,000 rounds and helped blunt the Japanese thrust, which ended by dawn of 3 January. Nowhere did the Japanese crack the lines of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, or loosen its grip on Target Hill. The body of a Japanese officer killed at Target Hill yielded documents that cast new light on the Japanese defenses south of Suicide Creek. A crudely drawn map revealed the existence of Aogiri Ridge, an enemy strongpoint unknown to General Shepherd's intelligence section. Observers on Target Hill tried to locate the ridge and the trail network the enemy was using, but the jungle canopy frustrated their efforts.

While the Marines on Target Hill tabulated the results of the fighting there—patrols discovered 40 bodies, and captured documents, when translated, listed 46 Japanese killed, 54 wounded, and two missing—and used field glasses to scan the jungle south of Suicide Creek, the 17th Marines completed the road that would enable medium tanks to test the defenses of that stream. During the afternoon of 3 January, a trio of Sherman tanks reached the creek only to discover that the bank dropped off too sharply for them to negotiate. The engineers sent for a bulldozer, which arrived, lowered its blade, and began gouging at the lip of the embankment. Realizing the danger if tanks succeeded in crossing the creek, the Japanese opened fire on the bulldozer, wounding the driver. A volunteer climbed onto the exposed driver's seat and took over until he, too, was wounded. Another Marine stepped forward, but instead of climbing onto the machine, he walked along side, using its bulk for cover as he manipulated the controls with a shovel and an axe handle. By dark, he had finished the job of converting the impassable bank into a readily negotiated ramp.

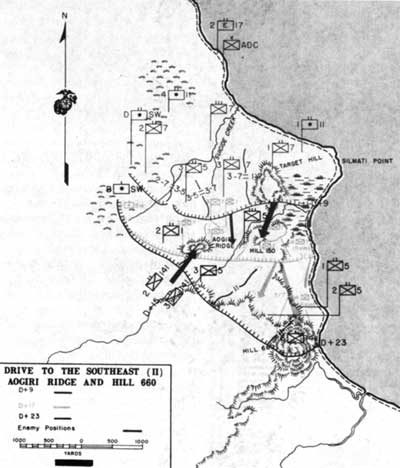

On the morning of 4 January, the first tank clanked down the ramp and across the stream. As the Sherman emerged on the other side, Marine riflemen cut down two Japanese soldiers trying to detonate magnetic mines against its sides. Other medium tanks followed, also accompanied by infantry, and broke open the bunkers that barred the way. The 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, and the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, surged onward past the creek, squeezing out the 2d Battalion, 7th Marines, which crossed in the wake of those two units to come abreast of them on the far right of the line that closed in on the jungle concealing Aogiri Ridge. The 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, thereupon joined the southward advance, tying in with the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, to present a four-battalion front that included the 2d Battalion and 3d Battalions, 7th Marines. Once across Suicide Creek, the Marines groped for Aogiri Ridge, which for a time simply seemed to be another name for Hill 150, a terrain feature that appeared on American maps. The advance rapidly overran the hill, but Japanese resistance in the vicinity did not diminish. On 7 January, enemy fire wounded Lieutenant Colonel David S. MacDougal, commanding officer of the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines. His executive officer, Major Joseph Skoczylas, took over until he, too, was wounded. Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. Puller, temporarily in command of the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, assumed responsibility for both battalions until the arrival on the morning of 8 January of Lieutenant Colonel Lewis W. Walt, recently assigned as executive officer of the 5th Marines, who took over the regiment's 3d Battalion.

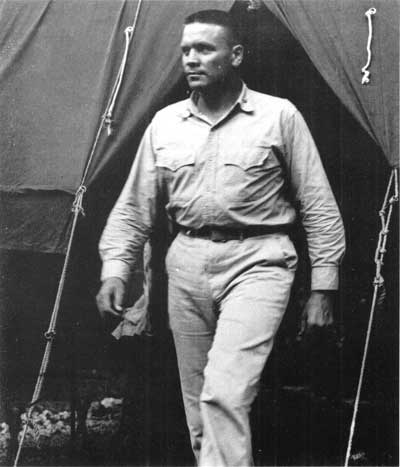

Upon assuming command of the battalion, Walt continued the previous day's attack. As his Marines braved savage fire and thick jungle, they began moving up a rapidly steepening slope. As night approached, the battalion formed a perimeter and dug in. Random Japanese fire and sudden skirmishes punctuated the darkness. The nature of the terrain and the determined resistance convinced Walt that he had found Aogiri Ridge. Walt's battalion needed the shock action and firepower of tanks, but drenching rain, mud, and rampaging streams stopped the armored vehicles. The heaviest weapon that the Marines managed to bring forward was a single 37mm gun, manhandled into position on the afternoon of 9 January, While the 11th Marines hammered the crest of Aogiri Ridge, the 1st and 3d Battalions, 7th Marines, probed the flanks of the position and Walt's 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, pushed ahead in the center, seizing a narrow segment of the slope, its apex just short of the crest. By dusk, said the 1st Marine Division's special action report, Walt's men had "reached the limit of their physical endurance and morale was low. It was a question of whether or not they could hold their hard-earned gains." The crew of the 37mm gun opened fire in support of the afternoon's final attack, but after just three rounds, four of the nine men handling the weapon were killed or wounded. Walt called for volunteers; when no one responded, he and his runner crawled to the gun and began pushing the weapon up the incline. Twice more the gun barked, cutting a swath through the undergrowth, and a third round of canister destroyed a machine gun. Other Marines then took over from Walt and the runner, with new volunteers replacing those cut down by the enemy. The improvised crew kept firing canister rounds every few yards until they had wrestled the weapon to the crest. There the Marines dug in, as close as ten yards to the bunkers the Japanese had built on the crest and reverse slope.

At 0115 on the morning of 10 January, the Japanese emerged from their positions and charged through a curtain of rain, shouting and firing as they came. The Marines clinging to Aogiri Ridge broke up this attack and three others that followed, firing off almost all their ammunition in doing so. A carrying party scaled the muddy slope with belts and clips for the machine guns and rifles, but there barely was time to distribute the ammunition before the Japanese launched the fifth attack of the morning. Marine artillery tore into the enemy, as forward observers, their vision obstructed by rain and jungle, adjusted fire by sound more than by sight, moving 105mm concentrations to within 50 yards of the Marine infantrymen. A Japanese officer emerged from the darkness and ran almost to Walt's foxhole before fragments from a shell bursting in the trees overhead cut him down. This proved to be the high-water mark of the counterattack against Aogiri Ridge, for the Japanese tide receded as the daylight grew brighter. At 0800, when the Marines moved forward, they did not encounter even one living Japanese on the terrain feature they renamed Walt's Ridge in honor of their commander, who received the Navy Cross for his inspirational leadership.

One Japanese stronghold in the vicinity of Aogiri Ridge still survived, a supply dump located along a trail linking the ridge to Hill 150. On 11 January, Lieutenant Colonel Weber's 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, supported by a pair of half-tracks and a platoon of light tanks, eliminated this pocket in four hours of fighting. Fifteen days of combat since the landings on 26 December, had cost the division 180 killed and 636 wounded in action. The next objective, Hill 660, lay at the left of General Shepherd's zone of action, just inland of the coastal track. The 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, commanded since 9 January by Lieutenant Colonel Henry W. Buse, Jr., got the assignment of seizing the hill. In preparation for Buse's attack, Captain Joseph W. Buckley, commander of the Weapons Company, 7th Marines, set up a task force to bypass Hill 660 and block the coastal trail beyond that objective. Buckley's group—two platoons of infantry, a platoon of 37mm guns, two light tanks, two half-tracks mounting 75mm guns, a platoon of pioneers from the 17th Marines with a bulldozer, and one of the Army's rocket-firing DUKWs—pushed through the mud and set up a road block athwart the line of retreat from Hill 660. The Japanese directed long-range plunging fire against Buckley's command as it advanced roughly one mile along the trail. Because of their flat trajectory, his 75mm and 37mm guns could not destroy the enemy's automatic weapons, but the Marines succeeded in forcing the hostile gunners to keep their heads down. As they advanced, Buckley's men unreeled telephone wire to maintain contact with higher headquarters. Once the roadblock was in place and camouflaged, the captain requested that a truck bring hot meals for his men. When the vehicle bogged down, he sent the bulldozer to push it free.

After aerial bombardment and preparatory artillery fire, Buse's battalion started up the hill at about 0930 on 13 January. His supporting tanks could not negotiate the ravines that scarred the hillside. Indeed, the going became so steep that riflemen sometimes had to sling arms, seize handholds among the vines, and pull themselves upward. The Japanese suddenly opened fire from hurriedly dug trenches at the crest, pinning down the Marines climbing toward them until mortar fire silenced the enemy weapons, which lacked overhead cover. Buse's riflemen followed closely behind the mortar barrage, scattering the defenders, some of whom tried to escape along the coastal trail, where Buckley's task force waited to cut them down.

Apparently delayed by torrential rain, the Japanese did not counterattack Hill 660 until 16 January. Roughly two companies of Katayama's troops stormed up the southwestern slope only to be slaughtered by mortar, artillery, and small-arms fire. Many of those lucky enough to survive tried to break through Buckley's roadblock, where 48 of the enemy perished. With the capture of Hill 660, the nature of the campaign changed. The assault phase had captured its objective and eliminated the possibility of a Japanese counterattack against the airfield complex. Next, the Marines would repulse the Japanese who harassed the secondary beachhead at Cape Merkus and secure the mountainous, jungle-covered interior of Cape Gloucester, south of the airfields and between the Green and Yellow Beaches.

|