| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

Cape Gloucester: The Green Inferno by Bernard C. Nalty The Capture of the Cape Gloucester Airfields The 1st Marine Division's overall plan of maneuver called for Colonel Frisbie's Combat Team C, the reinforced 7th Marines, to hold a beach head anchored at Target Hill, while Combat Team B, Colonel William A. Whaling's 1st Marines, reinforced but without the 2d Battalion ashore at Green Beach, advanced on the airfields. Because of the buildup in preparation for the attack on Conoley's battalion, General Rupertus requested that Kreuger release the division reserve, Combat Team A, Colonel John T. Selden's reinforced 5th Marines. The Army general agreed, sending the 1st and 2d Battalions, followed a day later by the 3d Battalion. The division commander decided to land the team on Blue Beach, roughly three miles to the right of the Yellow Beaches. The use of Blue Beach would have placed the 5th Marines closer to Cape Gloucester and the airfields, but not every element of Selden's Combat Team A got the word. Some units touched down on the Yellow Beaches instead and had to move on foot or in vehicles to the intended destination. While Rupertus laid plans to commit the reserve, Whaling's combat team advanced toward the Cape Gloucester airfields. The Marines encountered only sporadic resistance at first, but Army Air Forces light bombers spotted danger in their path—a maze of trenches and bunkers stretching inland from a promontory that soon earned the nickname Hell's Point. The Japanese had built these defenses to protect the beaches where Matsuda expected the Americans to land. Leading the advance, the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel Hankins, struck the Hell's Point position on the flank, rather than head-on, but overrunning the complex nevertheless would prove a deadly task.

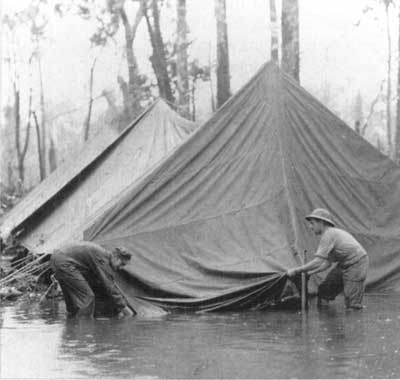

Rupertus delayed the attack by Hankins to provide time for the division reserve, Selden's 5th Marines, to come ashore. On the morning of 28 December, after a bombardment by the 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, and strikes by Army Air Forces A-20s, the assault troops encountered another delay, waiting for an hour so that an additional platoon of M4 Sherman medium tanks could increase the weight of the attack. At 1100, Hankins's 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, moved ahead, Company I and the supporting tanks leading the way. Whaling, at about the same time, sent his regiment's Company A through swamp and jungle to seize the inland point of the ridge extending from Hell's Point. Despite the obstacles in its path, Company A burst from the jungle at about 1145 and advanced across a field of tall grass until stopped by intense Japanese fire. By late afternoon, Whaling abandoned the maneuver. Both Company A and the defenders were exhausted and short of ammunition; the Marines withdrew behind a barrage fired by the 2d Battalion, 11th Marines, and the Japanese abandoned their positions after dark. Roughly 15 minutes after Company A assaulted the inland terminus of the ridge, Company I and the attached tanks collided with the main defenses, which the Japanese had modified since the 26 December landings, cutting new gunports in bunkers, hacking fire lanes in the undergrowth, and shifting men and weapons to oppose an attack along the coastal trail parallel to shore instead of over the beach. Advancing in a drenching rain, the Marines encountered a succession of jungle covered, mutually supporting positions protected by barbed wire and mines. The hour's wait for tanks paid dividends, as the Shermans, protected by riflemen, crushed bunkers and destroyed the weapons inside. During the fight, Company I drifted to its left, and Hankins used Company K, reinforced with a platoon of medium tanks, to close the gap between the coastal track and Hell's Point itself. This unit employed the same tactics as Company I. A rifle squad followed each of the M4 tanks, which cracked open the bunkers, twelve in all, and fired inside; the accompanying riflemen then killed anyone attempting to fight or flee. More than 260 Japanese perished in the fighting at Hell's Point, at the cost of 9 Marines killed and 36 wounded.

With the defenses of Hell's Point shattered, the two battalions of the 5th Marines, which came ashore on the morning of 29 December, joined later that day in the advance on the airfield. The 1st Battalion, commanded by Major William H. Barba, and the 2d Battalion, under Lieutenant Colonel Lewis H. Walt, moved out in a column, Barba's unit leading the way. In front of the Marines lay a swamp, described as only a few inches deep, but the depth, because of the continuing downpour, proved as much as five feet, "making it quite hard," Selden acknowledged, "for some of the youngsters who were not much more than 5 feet in height." The time lost in wading through the swamp delayed the attack, and the leading elements chose a piece of open and comparatively dry ground, where they established a perimeter while the rest of the force caught up. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, attacking through that regiment's 3d Battalion, encountered only scattered resistance, mainly sniper fire, as it pushed along the coast beyond Hell's Point. Half-tracks carrying 75mm guns, medium tanks, artillery, and even a pair of rocket-firing DUKWs supported the advance, which brought the battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Walker A. Reaves, to the edge of Airfield No. 2. When daylight faded on 29 December, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, held a line extending inland from the coast; on its left were the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, and the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, forming a semicircle around the airfield. The Japanese officer responsible for defending the airfields, Colonel Kouki Sumiya of the 53d Infantry, had fallen back on 29 December, trading space for time as he gathered his surviving troops for the defense of Razorback Hill, a ridge running diagonally across the southwestern approaches to Airfield No. 2. The 1st and 2d Battalions, 5th Marines, attacked on 30 December supported by tanks and artillery. Sumiya's troops had constructed some sturdy bunkers, but the chest-high grass that covered Razorback Hill did not impede the attackers like the jungle at Hell's Point. The Japanese fought gallantly to hold the position, at times stalling the advancing Marines, but the defenders had neither the numbers nor the firepower to prevail. Typical of the day's fighting, one platoon of Company F from Selden's regiment beat back two separate banzai attacks, before tanks enabled the Marines to shatter the bunkers in their path and kill the enemy within. By dusk on 30 December, the landing force had overrun the defenses of the airfields, and at noon of the following day General Rupertus had the American flag raised beside the wreckage of a Japanese bomber at Airfield No. 2, the larger of the airstrips.

The 1st Marine Division thus seized the principal objective of the Cape Gloucester fighting, but the airstrips proved of marginal value to the Allied forces. Indeed, the Japanese had already abandoned the prewar facility, Airfield No. 1, which was thickly overgrown with tall, coarse kunai grass. Craters from American bombs pockmarked the surface of Airfield No. 2, and after its capture Japanese hit-and-run raiders added a few of their own, despite antiaircraft fire from the 12th Defense Battalion. Army aviation engineers worked around the clock to return Airfield No. 2 to operation, a task that took until the end of January 1944. Army aircraft based here defended against air attacks for as long as Rabaul remained an active air base and also supported operations on the ground.

|