| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

Cape Gloucester: The Green Inferno by Bernard C. Nalty On the early morning of 26 December 1943, Marines poised off the coast of Japanese-held New Britain could barely make out the mile-high bulk of Mount Talawe against a sky growing light with the approach of dawn. Flame billowed from the guns of American and Australian cruisers and destroyers, shattering the early morning calm. The men of the 1st Marine Division, commanded by Major General William H. Rupertus, a veteran of expeditionary duty in Haiti and China and of the recently concluded Guadalcanal campaign, steeled themselves as they waited for daylight and the signal to assault the Yellow Beaches near Cape Gloucester in the northwestern part of the island. For 90 minutes, the fire support ships blazed away, trying to neutralize whole areas rather than destroy pinpoint targets, since dense jungle concealed most of the individual fortifications and supply dumps. After the day dawned and H-Hour drew near, Army airmen joined the preliminary bombardment. Four-engine Consolidated Liberator B-24 bombers, flying so high that the Marines offshore could barely see them, dropped 500-pound bombs inland of the beaches, scoring a hit on a fuel dump at the Cape Gloucester airfield complex and igniting a fiery geyser that leapt hundreds of feet into the air. Twin-engine North American Mitchell B-25 medium bombers and Douglas Havoc A-20 light bombers, attacking from lower altitude, pounced on the only Japanese antiaircraft gun rash enough to open fire.

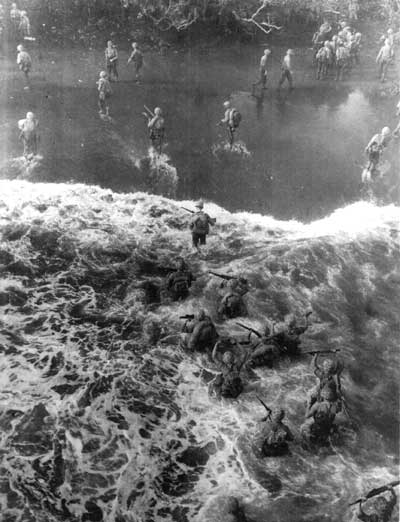

The warships then shifted their attention to the assault beaches, and the landing craft carrying the two battalions of Colonel Julian N. Frisbie's 7th Marines started shoreward. An LCI [Landing Craft, Infantry] mounting multiple rocket launchers took position on the flank of the first wave bound for each of the two beaches and unleashed a barrage intended to keep the enemy pinned down after the cruisers and destroyers shifted their fire to avoid endangering the assault troops. At 0746, the LCVPs [Landing Craft, Vehicles and Personnel] of the first wave bound for Yellow Beach 1 grounded on a narrow strip of black sand that measured perhaps 500 yards from one flank to the other, and the leading elements of the 3d Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William K. Williams, started inland. Two minutes later, Lieutenant Colonel John E. Weber's 1st Battalion, on the left of the other unit, emerged on Yellow Beach 2, separated from Yellow 1 by a thousand yards of jungle and embracing 700 yards of shoreline. Neither battalion encountered organized resistance. A smoke screen, which later drifted across the beaches and hampered the approach of later waves of landing craft, blinded the Japanese observers on Target Hill overlooking the beachhead, and no defenders manned the trenches and log-and-earth bunkers that might have raked the assault force with fire.

The Yellow Beaches, on the east coast of the broad peninsula that culminated at Cape Gloucester, provided access to the main objective, the two airfields at the northern tip of the cape. By capturing this airfield complex, the reinforced 1st Marine Division, designated the Backhander Task Force, would enable Allied airmen to intensify their attack on the Japanese fortress of Rabaul, roughly 300 miles away at the northeastern extremity of New Britain. Although the capture of the Yellow Beaches held the key to the New Britain campaign, two subsidiary landings also took place: the first on 15 December at Cape Merkus on Arawe Bay along the south coast; and the second on D Day, 26 December, at Green Beach on the northwest coast opposite the main landing sites. Major General William H. Rupertus

Major General William H. Rupertus, who commanded the 1st Marine Division on New Britain, was born at Washington, D.C., on 14 November 1889 and in June 1913 graduated from the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service School of Instruction. Instead of pursuing a career in this precursor of the U.S. Coast Guard, he accepted appointment as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. A vigorous advocate of rifle marksmanship throughout his career, he became a member of the Marine Corps Rifle Team in 1915, two years after entering the service, and won two major matches. During World War I, he commanded the Marine detachment on the USS Florida, assigned to the British Grand Fleet. Between the World Wars, he served in a variety of assignments. In 1919, he joined the Provisional Marine Brigade at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, subsequently becoming inspector of constabulary with the Marine-trained gendarmerie and finally chief of the Port-au-Prince police force. Rupertus graduated in June 1926 from the Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and in January of the following year became Inspector of Target Practice for the Marine Corps. He had two tours of duty in China and commanded a battalion of the 4th Marines in Shanghai when the Japanese attacked the city's Chinese defenders in 1937. During the Guadalcanal campaign, as a brigadier general, he was assistant division commander, 1st Marine Division, personally selected for the post by Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, the division commander, whom he succeeded when Vandegrift left the division in July 1943. Major General Rupertus led the division on New Britain and at Peleliu. He died of a heart attack at Washington, D.C., on 25 March 1945, and did not see the surrender of Japan, which he had done so much to bring about.

|