| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

A CLOSE ENCOUNTER: The Marine Landing on Tinian by Richard Harwood The Drive South Lieutenant Colonel William W. "Bucky" Buchanan was the assistant naval gunfire officer for the 4th Division at Tinian. His career later took him to Vietnam. After his retirement as a brigadier general he recalled the Tinian campaign:

The grouse-shooting metaphor is simplistic but even the 4th Division commander, Major General Clifton B. Cates, thought the campaign had its sporting aspects: "The fighting was different from most any that we had experienced because it was good terrain . . . . It was a good clean operation and I think the men really enjoyed it."

Before the "brush beating" could begin in proper order, three things needed to be achieved. First, the 2d Marine Division had to be put ashore. This task was completed on the morning of 26 July—Jig plus 2. Second, Japanese stragglers and pockets of resistance in the island's northern sector had to be squashed. That job, for all practical purposes, was pretty well completed on the 26th as the 2d Division swept across the Ushi Point airfields, reached the east coast, and made a turn to the south. (Two days later, Seabees had the Ushi Point fields in operation for Army P-47 Thunderbolt fighters). Also on the 26th, the 4th Division had seized Mount Maga in the center of the island and had forced Colonel Ogata and his staff to abandon their command post on Mount Lasso which fell to the Marines without a struggle. The third objective—to create for the drive south a skirmish line of infantry and tanks stretching all the way across the island—was also accomplished on the 26th. The 4th Division lined up in the western half of the island with the 23d Marines on the coast, the 24th in the center, and the 25th on the left flank. The 2d Division lined up with the 2d Marines on the east coast and the 6th Marines in the center, tied in to the 25th. The 8th Marines remained in the north to mop up. All this was accomplished with only minor casualties. For 26 July, for example, the 2nd Division reported two killed and 14 wounded. The heaviest losses since the first day and night of fighting had been sustained by the 14th Marines, the 4th Division's artillery regiment, in the hours following the Japanese counterattack. An enemy shell hit the 1st Battalion's fire direction center killing the battalion commander (Lieutenant Colonel Harry J. Zimmer), the intelligence officer, the operations officer, and seven other staff members; 14 other Marines at the battalion headquarters were wounded. Virtually all of the casualties sustained by that regiment during the Tinian campaign were taken on this single day, 25 July: 13 of the 14 killed, and 22 of the 29 wounded.

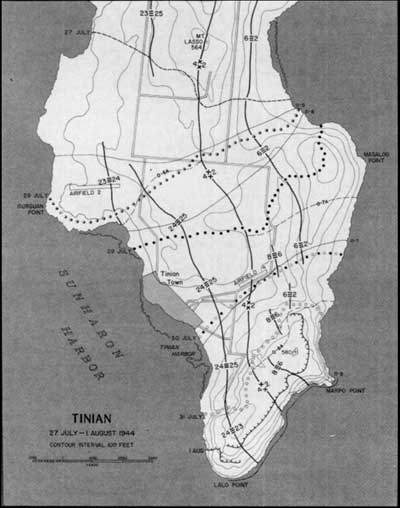

On the morning of 27 July, the "brush beating" drive to the south began in earnest. General Schmidt's plan for the first two days of the drive alternated the main thrust between the two divisions. In the official history of the operation, the tactic was likened to "a man elbowing his way through the crowd," swinging one arm and then the other. The 2d Division got the heavier work on the 27th. XXIV Corps Artillery, firing from southern Saipan, softened up suspected enemy positions early in the morning and the division jumped off at 0730. It advanced rapidly, harassed by sporadic small arms fire. By 1345 it had reached its objective, gaining about 4,000 yards in just over six hours. The 4th Division moved out late in the morning against "negligible opposition," reached its objective by noon and then called it a day. A Japanese prisoner complained to his captors, "You couldn't drop a stick without bringing down artillery." The next morning, 28 July, the 4th got the "swinging elbow" job. It was now evident that the remaining Japanese defenders were rapidly retiring to the hills and caves along the southern coast. So opposition to the Marine advance was virtually nil. The 4th moved more than two miles in less than four hours with troops riding on half-tracks and tanks. Jumping off again early in the afternoon in "blitz fashion," they overran the airfield at Gurguan Point, led by Major Richard K. Schmidt's 4th Tank Battalion, and quit for the day at 1730 after gaining 7,300 yards—a little more than four miles. The 2d Division, given light duty under the Schmidt plan, moved ahead a few hundred yards, reached its objective in a couple of hours and dug in to await another morning. General Cates later recalled how he spurred on his 4th Division troops: "I said, 'Now, look here men, the [Hawaiian] island of Maui is waiting for us. See those ships out there? The quicker you get this over with, the quicker we'll be back there.' They almost ran over that island." On the 29th General Schmidt dropped the "elbowing" tactic and ordered both divisions to move as far and as fast as "practical." Opposition had been so light that preparatory fires were canceled to save unneeded withdrawals from the diminishing supplies of artillery shells left on Saipan and to prevent "waste of naval gunfire on areas largely deserted by the enemy." The 2d Marines on the eastern terrain ran into pockets of resistance on a hill at Masalog Point; the 6th Marines encountered a 20-man Japanese patrol that attempted to penetrate the regiment's lines after dark. The 25th took sniper fire as it moved through cane fields and later in the day engaged in a heavy firefight with Japanese troops fighting from dug in positions. The Marines suffered several casualties and one of their tanks was disabled in this fight. But the resistance was overcome. The 24th Marines, operating near the west coast, ran into Japanese positions that included a series of mutually supporting bunkers. The 4th Tank Battalion reported that the area "had to be overrun twice by tanks" before resistance ended. By nightfall, more than half of Tinian island was in Marine hands. Troops of the 4th Division could see Tinian Town from their foxholes. This was good for morale but the night was marred by the weather and enemy activity. A soaking rain fell through the night. Enemy mortar tubes and artillery pieces fired incessantly, drawing counterbattery fire from Marine gunners. There were probes in front of the 3d Battalion, 25th Marines, silenced by mortar and small arms fire; 41 Japanese bodies were found in the area at daylight. On 30 July—Jig plus 6—Tinian Town became the principal objective of the 4th Division and, specifically, Colonel Franklin A. Hart's 24th Marines. At 0735 all of the division's artillery battalions laid down preparatory fires in front of the Marine lines. After 10 minutes, the firing stopped and the troops moved out. At the same time, two destroyers and cruisers lying in Sunharon Harbor off the Tinian Town beaches began an hour-long bombardment of slopes around the town in support of the Marines. The regiment's 1st Battalion had advanced 600 yards when it came under heavy fire from caves along the coast north of the town. With the help of tanks and armored amphibians operating offshore this problem was overcome. Flamethrowing tanks worked over the caves, allowing engineers to seal them up with demolition charges. In one cave, a 75mm gun was destroyed. The regiment entered the ruins of Tinian Town at 1420. Except for one Japanese soldier who was eliminated on the spot, the town was deserted. After searching through the rubble for snipers and documents, the Marines drove on to the O-7 line objective south of town. Their greatest peril was from mines and booby traps planted in beach areas and roads. As the 24th moved south, the 25th Marines were seizing Airfield Number 4 on the eastern outskirts of Tinian Town. The unfinished facility, a prisoner revealed, was being rushed to completion to accommodate relief planes promised by Tokyo. Only one aircraft was parked on the crushed coral air strip—a small, Zero-type fighter. Flying suits, goggles, and other equipment were found in a supply room.

Enroute to the airfield, the 25th had taken light small arms fire and while crossing the airstrip was mortared from positions to the south. This was the 25th's last action of the Tinian campaign. It went into reserve and was relieved that night by units of the 23d Marines and the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines. The 2d Division, operating to the east of the 4th, ran into occasional opposition from machine gun positions and a 70mm howitzer. The 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, had the roughest time. After silencing the howitzer, it attacked across an open field and chased a Japanese force into a large cave where, with the help of a flame-throwing tank, 89 Japanese were killed and four machine guns were destroyed. Soon afterward the battalion came under mortar fire. "It is beyond my memory as to the number of casualties the 3d Battalion suffered at that time," the unit's commander, Lieutenant Colonel Walter F. Layer, later reported. "I personally rendered first aid to two wounded Marines and remember seeing six or seven Marines who were either wounded or killed by that enemy mortar fire. Tanks and half-tracks . . . took the enemy under fire, destroying the enemy mortars." These were minor delays. The division reached its objective on time and was dug in by 1830. About 80 percent of the island was now in American hands.

|