| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

A CLOSE ENCOUNTER: The Marine Landing on Tinian by Richard Harwood The Landing Force: Who, Where, When The task of seizing Tinian was assigned to the two Marine divisions on Saipan—the 2d and the 4th. The third division on the island—the Army's 27th Infantry—would remain on Saipan in reserve. All three had been severely battered during the Saipan campaign, suffering more than 14,000 casualties, including nearly 3,200 dead. For the 2d Marine Division, the Tinian battle would be the fourth time around in a span of little more than 18 months. The division left Guadalcanal in February 1943, having suffered 1,000 battle casualties. Another 12,500 men had diagnosed cases of malaria. Nine months later—on 20 November 1943—the division had gone through one of the most intense 72 hours of combat in the history of island warfare at Tarawa. It sustained 3,200 casualties, including nearly a thousand dead. Ten weeks before Tarawa, the division was still malaria-ridden, with troops being hospitalized for the disease at the rate of 40 a day. The ranks were filled with gaunt men whose skins were yellowed by daily doses of Atabrine pills. The Saipan operation seven months later, led by division commander Major General Thomas E. Watson, took a heavy toll of these men—5,000 wounded, 1,300 dead. Watson had earned a reputation at Saipan as a hard-charging leader. When the division stalled fighting its way up Mount Topatchau, he was unimpressed. The historian Ronald Spector wrote, in the midst of that effort, "he was heard shouting over a field telephone, 'There's not a god damn thing up on that hill but some Japs with machine guns and mortars. Now get the hell up there and get them!'" His assistant division commander was Brigadier General Merritt A. "Red Mike" Edson, who was awarded a Medal of Honor for his heroism on Guadalcanal. The 4th Division had had a busy, if slightly less demanding, year as well. It went directly into combat after its formation at Camp Pendleton, California, landing on 31 January 1944 in the Marshall Islands where it suffered moderate casualties—fewer than 800 men—in the capture of Roi-Namur. At Saipan its losses reached 6,000, including about 1,000 dead. The Tinian landing would be its third in a little over six months and would be the first under a new divisional commander—Major General Clifton B. Cates, a well-decorated World War I veteran, who would be come the 19th Commandant of the Marine Corps in 1948.

Still, "the morale of the troops committed to the Tinian operation was generally high," then-Major Carl W Hoffman wrote in the official history of the battle. "This fact takes on significance only when it is recalled that the Marines involved had just survived a bitter 25-day struggle and that, with only a fortnight lapse (as distinguished from a fortnight rest), they were again to assault enemy-held shores . . . . [Their] spirit . . . was revealed more in a philosophical shrug, accompanied with a 'here-we go-again' remark, than in a resentful complaint [at] being called upon again so soon."

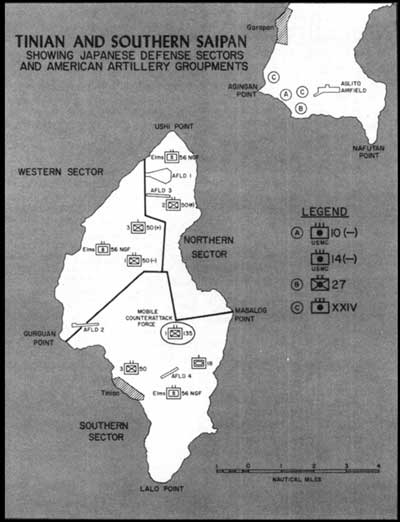

The morale of the troops was sustained by the preinvasion fires directed at Tinian. For Jig minus 1 and Jig Day (Jig being the name given to D Day at Tinian), Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill, commander of the Northern Landing Force, had divided the island into five fire support sectors, assigning specific ships to each. His purpose was two-fold: destruction and deception to confuse and deceive the Japanese as to the landing intentions of the Marines. Tinian Town, under this scheme, got the heaviest pounding the day before the landing—almost 3,000 rounds of 5- to 16-inch shells from the battleships Colorado, Tennessee, and California, the cruiser Cleveland, and seven destroyers: Ramey, Wadleigh, Norman Scott, Monssen, Waller, Pringle and Philip. Colorado had the best day, knocking out with 60 rounds of 16-inch shells the two 6-inch coastal defense guns the Japanese had emplaced on the west coast near Faibus San Hilo Point, guns that easily could have covered the White Beaches. Firing on the White Beach area itself was minimal for purposes of deception and for lack of suitable targets. The cruiser Louisville fired 390 rounds into the area before calling it a day. There was a lot of air activity on the 23d. At three periods during the day, naval gunfire and artillery barrages were halted to allow massive air strikes on railroad junctions, pillboxes, villages, gun emplacements, cane fields, and the beaches at Tinian Town. More than 350 Navy and Army planes took part, dropping 500 bombs, 200 rockets, 42 incendiary clusters, and 34 napalm bombs. This was only the second use of napalm during the Pacific War; napalm bombs were first used on Tinian the day before.

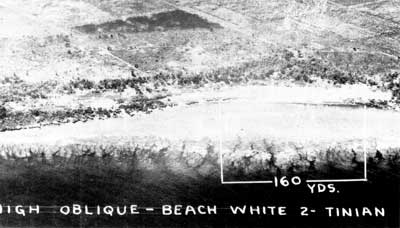

That evening, 37 LSTs at anchor off Saipan were loaded with 4th Marine Division troops. Rations for three days, water and medical supplies, ammunition, vehicles, and other equipment had been pre-loaded, beginning on 15 July. The troops were going to travel light: a spoon, a pair of socks, insect repellant, and emergency supplies in their pockets, and no pack on their backs. "Close at hand," the historians Jeter Isely and Philip Crowl wrote in their classic The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, "rode the ships of the two transport divisions that would carry two regiments of the 2d Marine Division on a diversionary feint against Tinian Town and would later disembark them along with the third regiment across the northwestern beaches." (A similar feint was made by 2d Division Marines less than a year later off the southeast beaches of Okinawa, and by the same division lying off Kuwait City nearly 50 years later in the Desert Storm operation). The 4th was designated the assault division for Tinian. The beaches were not wide enough to accommodate battalions landing abreast, much less divisions. Instead, the assault troops would land by columns—squads, platoons, and companies. The 2d Division would follow on after taking part in the massive feint off the beaches of Tinian Town, hoping to tie down the main Japanese defense forces and spring the surprise of a landing over the lightly defended northern beaches. General Clifton B. Cates, USMC

Clifton B. Cates, a native Tennessean, was commissioned in 1917, and was sent to France with the 6th Marines in World War I. He had outstanding service in five major engagements of the war, and returned to the United States a well-decorated young officer after his tour in the occupation of Germany. One of his early assignments following the war was as aide to Major General Commandant George Barnett. During his more than 37 years as a Marine, Cates was one of the few officers who held commands of a platoon, a company, a battalion, a regiment, and a division in combat. He was the 19th Commandant of the Marine Corps at the outset of the Korean War. His assignments during the interwar years consisted of a combination of schooling, staff assignments, and command, such as his tour as battalion commander in the 4th Marines, then in Shanghai. In 1940, he took command of the Basic School, then in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. He took command of the 1st Marines in May 1942. In World War II, Cates commanded the 1st Marines in the landing on Guadalcanal. After returning to the States, he was promoted to brigadier general. He went back to the Pacific war in mid-1944 to take command of the 4th Marine Division in time for the Tinian operation. He also led it in the Iwo Jima assault, and was decorated at the end of the fighting with his second Distinguished Service Medal. Part of the citation accompanying the medal reads: "Repeatedly disregarding his own personal safety, Major General Cates traversed his own front lines daily to rally his tired, depleted units and by his undaunted valor, tenacious perseverance, and staunch leadership in the face of overwhelming odds, constantly inspired his stout-hearted Marines to heroic effort during critical phases of the campaign." On 1 January 1948, General Cates took over as Commandant of the Marine Corps, remaining until 31 December 1951, when he reverted to the three stars of a lieutenant general and began his second tour as Commandant of the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico, Virginia. General Cates retired on 30 June 1954. He died on 4 June 1970. To give the 4th more punch immediately after landing, the 2d was stripped of some of its firepower, such as tank and artillery units. It would, accordingly, be at the lowest strength at Tinian of any Marine division involved in an amphibious operation in World War II. Despite these additions, the 4th, too, would be understrength—"skinny" was the descriptive word used by Lieutenant Colonel Justice M. "Jumping Joe" Chambers, commander of the 3d Battalion, 25th Marines, who was to earn a Medal of Honor in the Iwo Jima operation little more than six months later. The division's infantry battalions had received only one replacement draft after the Saipan fighting. At full strength they averaged 880 men; at Tinian the average strength was down by more than 35 percent to 565. For all these reasons—combat fatigue, heavy losses during previous weeks and months, and under-strength units—the Marines on Tinian would play a cautious game. Admiral Turner had said he would give them two weeks to seize the island. Major General Harry Schmidt, who relieved Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith as VAC commander, promised to get it done in 10 days. In the event, the island was secured after nine days. In retrospect, analysts say the operation could have been finished off sooner by more aggressive tactics. Time, however, was no great factor; the relatively slow pace of the operation probably kept casualties at a minimum and reduced the probabilities of troop fatigue. Tinian was easy on the eyes, but the heat and humidity were brutal, the cane fields were hard going, and it was the season of monsoons.

|