|

A CLOSE ENCOUNTER: The Marine Landing on Tinian

by Richard Harwood

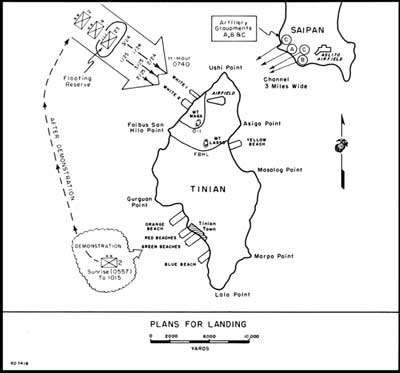

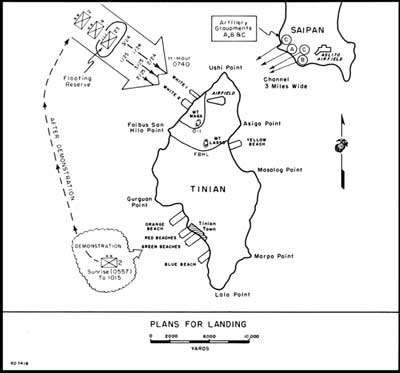

The Landing

The assault plan assigned White Beach 1 to the 24th

Marines and White Beach Two to the 25th. In the vanguard for the 24th

was Company E of the 2d Battalion—200 men commanded by Captain Jack

F. Ross, Jr. Company A of the 1st Battalion, commanded by Captain Irving

Schechter, followed and by 0820 the entire 2d Battalion, commanded by

Major Frank A. Garretson, was ashore.

Almost simultaneously, two battalions of the 25th

Marines loaded into 16 LVTs landed in columns of companies on White

Beach 2. The 2d Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Lewis C. Hudson, Jr.,

was on the right; the 3d Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Chambers) was on

the left.

The units of the 24th, loaded into 24 LVTs, crossed

the line of departure—3,000 yards offshore—at 0717. Ahead of

them, 30 LCIs (landing craft, infantry) and a company of the 2d Armored

Amphibian Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Reed M. Fawell,

Jr., raked the beaches with barrage rockets and automatic cannon fire.

On the 26-minute run to the beach, the troop-laden LVTs took scattered

and ineffectual rifle and machine gun fire.

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

At White 1, members of a small Japanese beach

detachment, holed up in caves and crevices, resisted the landing with

intense small arms fire. But they were silenced quickly by Company E

gunners.

Within an hour, the entire 1st and 2d Battalions of

the 24th were ashore on White 1, preparing to move in land. The 2d

Battalion encountered sporadic artillery, mortar, and small arms fire

during the first 200 yards of its advance. After that, Garretson later

said, the battalion had a "cake walk" for the rest of the day, gaining

1,400 yards and reaching its O-1 line objective by 1600. He occupied the

western edge of Airfield No. 3 and cut the main road linking Airfield

No. 1 with the east coast and southern Tinian. Only occasional small

arms fire was encountered before the battalion dug in for the

night.

On Garretson's left, the 1st Battalion, commanded by

Lieutenant Colonel Otto Lessing, was slowed by heavy fires from cave

positions and patches of heavy vegetation. Flamethrower tanks were sent

up against these positions, but the Japanese held on. As a result,

Lessing pulled up late in the afternoon 400 yards short of his

objective. This left a gap between his perimeter and Garretson's. To

fill it, the regiment's 3d Battalion, waiting in reserve at the beach,

was called up.

Almost simultaneously, the 25th ran into problems.

The beach and surrounding area had been methodically seeded with mines

which neither UDT teams nor offshore gunners had been able to destroy.

It took six hours to clear them out and in the process three LVTs and a

jeep were blown up. The beach defenses also included a sprinkling of

booby traps which had to be dealt with—watches and cases of beer,

for example, all wired to explode in the hands of careless souvenir

hunters.

Behind the beach, troops from Ogata's 50th

Regiment put up a vigorous defense with mortars, anti-tank and

anti-boat guns, and other automatic weapons emplaced in pillboxes,

caves, fortified ravines, and field entrenchments. Two 47mm guns in

particular kept the Marines back on their heels. They finally bypassed

these troublesome positions. Later waves took them out, leaving 50 dead

Japanese in the gunpits.

The 3d Battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel

Chambers, later remembered a lot of confusion on the beach, "the

confusion you [always] get when you land, of getting the organization

together again." One of his company commanders, for example, was killed

a half-hour after landing and it took a while to get a replacement on

scene and up to speed. Then there was the problem of the mines and a

problem with artillery fire from the Japanese command post on Mount

Lasso, two-and-a-half miles away.

|

Tinian Defense Forces

Japanese military fortification of Tinian and other

islands in the chain had begun—in violation of the League of

Nations Mandate—in the 1930s. By 1944, the Tinian garrison numbered

roughly 9,000 army and navy personnel, bringing the island's total

population to nearly 25,000.

The 50th Infantry Regiment, detached from the

29th Division on Guam, was the principal fighting force. It had

been stationed near Mukden, Manchuria, from 1941 until its transfer in

March 1944 to Tinian. Many of its troops were veterans of the Manchurian

campaigns. The regiment was commanded by Colonel Kiyoshi [also spelled

"Keishi"] Ogata and consisted of three 880-man infantry battalions, a

75mm mountain artillery battalion equipped with 12 guns, engineer,

communication, and medical companies, plus a headquarters and various

specialized support units, including a company of 12 light tanks and an

anti-tank platoon. He also had a battalion of the 135th Infantry

Regiment with a strength of about 900 men. Altogether, slightly more

than 5,000 army troops were assigned to the island's defense.

The principal navy unit was the 56th Naval Guard

Force, a 1,400-man coastal defense unit, supplemented by four

construction battalions with a combined strength of 1,800 men. Other

naval units, totaling about 1,000 men, included ground elements of seven

aviation squadrons and a detachment of the 5th Base Force.

The navy personnel—about 4,200

altogether—were under the immediate command of Captain Oichi Oya.

Both Oya and Ogata were outranked on the island by Vice Admiral Kakuji

Kakuda, commander of the 1st Air Fleet with headquarters on

Tinian. But Kakuda, as the invasion neared, had no air fleet to command.

Of the estimated 107 planes based at Tinian's air fields, 70 had been

destroyed on the ground early in June by U.S. air strikes. By the time

of the Tinian landing on 24 July, none of Kakuda's planes were

operative.

Kakuda had a bad reputation. He was, by Japanese

physical standards, a hulking figure: more than six feet tall, weighing

more than 200 pounds. "He willingly catered," Hoffman wrote, "to his

almost unquenchable thirst for liquor; he lacked the fortitude to face

the odds arrayed against him at Tinian." Historian Frank Hough called

him "a drunk and an exceedingly unpleasant one, from all accounts."

On 15 July, nine days before the invasion, Kakuda and

his headquarters group attempted to escape via rubber boats to Aguijan

Island where they hoped to rendezvous with a Japanese submarine. This

effort failed. He tried again on five successive nights with the same

results, finally abandoning the effort on 21 July. He fled with his

party from Tinian Town to a cave on Tinian's east coast where they

awaited their fate. A Japanese prisoner who described Kakuda's escape

efforts assumed he had committed suicide after the American landing, but

this was never verified. Toward the end of the battle for Tinian, one of

Kakuda's orderlies led an American patrol to the cave. The patrol was

fired upon and two Marines were wounded. A passing group of Marine

pioneers sealed the cave with demolition charges but it is unknown

whether Kakuda was inside.

Admiral Kakuda in any case took no part in directing

the Japanese resistance. For purposes of defending the island, command

of both army and navy forces was assumed by Colonel Ogata, but

co-operation between the two service branches was less than complete.

Frictions were reflected in diaries found among the Japanese documents

captured on Tinian. A soldier in the 50th Regiment's artillery

battalion wrote:

9 March—The Navy stays in barracks buildings and

has liberty every night with liquor to drink and makes a big row.

We, on the other hand, bivouac in the rain and never

get out on pass. What a difference in discipline!

12 June—Our AA guns [manned by the Navy] spread

black smoke where the enemy planes weren't. Not one hit out of a

thousand shots. The Naval Air Group has taken to its heels.

15 June—The naval aviators are robbers . . .

When they ran off to the mountains, they stole Army provisions . . .

.

The defenses of Tinian were dictated by the geography

of the island. It is encircled by coral cliffs which rise from the

coastline and are a part of the limestone plateau underlying the island.

These cliffs range in height from 6 to 100 feet; breaks in the cliffline

are rare and where they occur are narrow, leaving little beach space for

an invasion force. Along the entire coastline of Tinian, only four

beaches were worthy of the name.

The largest and most suitable for use by an

amphibious force was in front of Tinian Town in Suharon Harbor. It

consisted of several wide, sandy strips. The harbor was mediocre but

provided in fair weather limited anchorage for a few ships which could

load and unload cargo at two piers available at Tinian Town.

From the beginning, Colonel Ogata assumed that this

beach would be the first choice of the Americans. Of the roughly 100

guns in fixed positions on the island—ranging from 7.7mm heavy

machine guns to 6-inch British naval rifles—nearly a third were

assigned to the defense of Tinian Town and its beaches and to the

airfield at Gurguan Point, two-and-a-half miles northwest of the town.

Within a two-mile radius of the town were the 2d Battalion of the

50th Infantry Regiment, 1,400 men of the 56th Naval Guard

Force, a tank company of the 18th Infantry Regiment, and the

1st Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment, which had been designated

as the mobile counterattack force.

Their area of responsibility extended to Laslo Point,

the southernmost part of the island and, on the east, to Masalog Point.

It was designated the "Southern Sector" in Ogata's defense plan.

The remainder of the island was divided into

northeastern and northwestern sectors. The northeastern sector included

the Ushi Point airfields and a potential landing beach 125 yards wide

south of Asiga Point on the east coast of the island. In this sector,

between 600 and 1,000 navy personnel were stationed around the Ushi

Airfields. The 2d Battalion of the 50th Infantry Regiment,

along with an engineer group, was stationed inland of Asagi Point. The

northwestern sector contained two narrow strips of beach 1,000 yards

apart. One of them was 60 yards wide and the other about 160. They were

popular with Japanese civilians. The sand was white and the water was

swimmable. They were known locally as the White Beaches and that is what

they were called when they were chosen—to the great surprise of the

Japanese—as the American invasion route.

This sector was defended very modestly by a single

company of infantry, an antitank squad, and, about 500 yards northeast

of the White Beaches, gun crews situated in emplacements containing one

37mm antitank gun, one 47mm antitank gun, and two 7.7mm machine

guns.

Ogata established his command post in a cave on Mount

Lasso in the center of the northern region, roughly equidistant—a

little over two miles—from beaches on either side of the

island.

He issued on 25 June an operation order saying "the

enemy on Saipan can be expected to be planning a landing on Tinian. The

area of that landing is estimated to be either Tinian Harbor or Asiga

Harbor [on the northeast coast]." Three days later he followed up with a

"Defense Force Battle Plan" which outlined only two contingencies:

(A) In the event the enemy lands at Tinian

Harbor.

(B) In the event the enemy lands at Asiga Bay.

On 7 July Ogata issued a "Plan for the Guidance of

Battle" ordering his men to be prepared not only for landings at Tinian

Town and Asiga Bay, but also for a counterattack in the event the

Americans were to invade across the White Beaches.

In each of the three sectors, according to his battle

plan, commanders were to be prepared to "destroy the enemy at the beach,

but [also] be prepared to shift two-thirds of the force elsewhere." His

reserve force was to "maintain fortified positions, counter-attack

points [and] maintain anti-aircraft observation and fire in its area."

The "Mobile Counterattack Force" must "advance rapidly to the place of

landings, depending on the situation and attack." In the event of

successful landings his forces would "counterattack to the water and . .

. destroy the enemy on beaches with one blow, especially where time

prevents quick movement of forces within the island." If things were to

go badly, "we will gradually fall back on our prepared positions in the

southern part of the island and defend them to the last man."

Some of these orders were contradictory and others

were impossible of execution. But despite the odds against

them—bereft of air or sea support and confronted by three heavily

armed divisions only three miles away on Saipan—the fighting spirit

of the Japanese forces had not been broken by 43 days of the heaviest

bombardment, up to then, of the Pacific war. One of the men of the

50th Infantry Regiment wrote in his diary on 30 June: "We have

spent twenty days under unceasing enemy bombardment and air raids but

have suffered only minor losses. Everyone from the Commanding Officer to

the lowest private is full of fighting spirit." His entry for 19 July,

five days before the American landings, was upbeat: "How exalted are the

gallant figures of the Force Commander, the Battalion Commander, and

their subordinates, who have endured the violent artillery and air

bombardment."

|

By late afternoon, Chambers' battalion had reached

its objective 1,500 yards inland in the center of the line and had tied

in on its left flank with Garretson of the 24th. The other battalions of

the 25th came up short of their O-1 line, creating before sun down a

crescent-shaped beachhead 3,000 yards wide at the shoreline and bulging

inland to a maximum depth of 1,500 yards.

The day's greatest confusion surrounded the landing

of the 23d Marines. The regiment had been held on LSTs (landing ships,

tank) in division reserve during the landing of the 24th and 25th. At

0730, the troops were ordered below to board LVTs parked cheek to jowl

on the tank decks. Their engines were running, spewing forth carbon

monoxide. Experience had shown that troops cooped up under these

conditions for more than 30 minutes would develop severe headaches,

become nauseous, and begin vomiting.

To avoid that problem and in the absence of a launch

order, the regimental commander, Colonel Louis R. Jones, soon unloaded

his men and sent them topside. They returned to the tank decks at 1030

when an order to load and launch finally was received. The regiment

debarked and eventually got ashore beginning at 1400 despite an

incredible series of communication breakdowns in which Jones at crucial

times was out of touch with the division and his battalions.

In addition to botched radio communications, Jones

was stuck in an LVT with a bad engine; it took him seven hours to get

ashore with his staff, leading to a division complaint about the

tardiness of his regiment. The division noted that "fortunately no

serious harm was done by [the] delay," but at the end of the operation

Jones left the division. He was promoted to brigadier general and

assigned as assistant division commander of the 1st Marine Division for

the Okinawa landings.

A similar muck-up occurred involving the 2d Marine

Division. After the feint at Tinian Town, the division sailed north and

lay offshore of the White Beaches through the day. At 1515, the landing

force commander, Major General Harry Schmidt, ordered a battalion from

the 8th Marines to land at White Beach to back up the 24th Marines.

Schmidt wanted the battalion ashore at 1600. Because of communication

and transport confusion the deadline was missed. It was 2000 when the

unit entered in its log ". . . dug in in assigned position."

On the other hand, the big things had gone well in

the morning and afternoon. By the standards of Tarawa and Saipan,

casualties were light—15 dead, 225 wounded. The body count for the

Japanese was 438. Despite drizzling rain, narrow beaches, and

undiscovered mines, 15,600 troops were put ashore along with great

quantities of material and equipment that included four battalions of

artillery, two dozen half-tracks mounting 75mm guns, and 48 medium and

15 flame-throwing tanks which found the Tinian terrain hospitable for

tank operations. The tanks had gotten into action early that morning,

leading the 24th in tank-infantry attacks. They also had come to the aid

of the 23d Marines as that regiment moved inland to take over the

division's right flank. The beachhead itself was of respectable size,

despite the failure of some units to reach their first-day objectives.

It extended inland nearly a mile and embraced defensible territory. On

the whole, it had not been a bad day's work.

|