|

A CLOSE ENCOUNTER: The Marine Landing on Tinian

by Richard Harwood

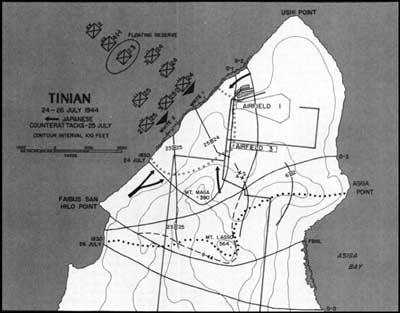

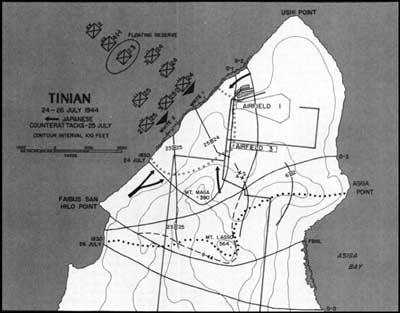

Counterattack

At about 1630, the 4th Division commander, General

Cates, ordered his forces to button up for the night. A nighttime

counterattack was expected. Barbed wire, preloaded on amphibian vehicles

(DUKWs), was strung all along the division front. Ammunition was stacked

at every weapons position. Machine guns were emplaced to permit

interlocking fields of fire. Target areas were assigned to mortar crews.

Artillery batteries in the rear were registered to hit probable enemy

approach routes and to fire illuminating shells if a lighted battlefield

was required. Of great importance, as it turned out, was the positioning

up front of 37mm guns and canister ammunition (antipersonnel shells

which fired large pellets for close-in fighting); in the night fighting

that followed, they inflicted severe losses on the enemy.

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

As the troops dug in to await whatever the night

would bring, the 24th Marines, backed up by the 1st Battalion, 8th

Marines, occupied the northern half of the defensive crescent. The 25th

and a battalion of the 23d occupied the southern half of the crescent

with the remainder of the 23d in reserve. On the beaches in the rear,

artillery battalions from the 10th and 14th Marines, engineer

battalions, and other special troops were on alert.

|

Preparatory Strikes

No battle in the Pacific was a "piece of cake." But

there was less apprehension among the Americans about the outcome at

Tinian than in any major operation of the war. Admiral Raymond A.

Spruance later described it as "probably the most brilliantly conceived

and executed amphibious operation of World War II." Lieutenant General

Holland M. Smith, commander of the Expeditionary Troops during the

seizure of the Marianas, called it "the perfect amphibious

operation."

It took place under optimal conditions for success.

The small Japanese garrison on the island had no hope of relief,

resupply, escape, or victory. Three miles away, across the narrow

Saipan Channel, three battle-tested American divisions—more than

50,000 men—were available for the inevitable invasion. For seven

weeks the bombardment from U.S. air and sea armadas, joined by the big

guns on Saipan, had been relentless, day and night.

The effect on Tinian's civilian inhabitants was

recorded by James L. Underhill, later a Marine lieutenant general, who

became the island's military commander at the end of the battle:

The state of these people was indescribable. They

came in with no possessions except the rags on their backs. They had

been under a two-month intense bombardment and shelling and many were

suffering from shell shock . . . They had existed on very scant rations

for six weeks and for the past week had had practically nothing to eat.

They had been cut off from their own water supply for a week and had

caught what rainwater they could in bowls and cans. Hundreds of them

were wounded and some of their wounds were gangrenous. Beri beri,

syphilis, pneumonia, dysentery, and tuberculosis were common. [They

needed] shelter, food, water, clothing, medical care, and

sanitation.

The bombardment began on 11 June—four days

before the Saipan invasion—when carrier planes from Vice Admiral

Marc A. Mitcher's Task Force 58 launched a three-and-a-half day

pummeling of all the principal Mariana Islands. A fighter sweep on the

first day, carried out by 225 Grumman Hellcats, destroyed about 150

Japanese aircraft and ensured American control of the skies over the

islands.

Following the raid, a member of the Japanese garrison

on Saipan, wrote in his diary: "For two hours, enemy planes ran amuck

and finally left leisurely amidst the unparalleledly inaccurate

antiaircraft fire. All we could do was watch helplessly."

Over the next two days, bombers hit the islands and

shipping in the area with no letup. There was a fatalistic diary entry

by one of the Tinian troops: "Now begins our cave life." Another

soldier wrote of the ineffectual antiaircraft fire—"not one hit out

of a thousand shots"—and reported that "the Naval Air Group has

taken to its heels." Yet another diarist was indignant, too: "The naval

aviators are robbers . . . When they ran off to the mountains they stole

Army provisions."

Fast battleships from Task Force 58 joined the

bombardment from long range on 13 June. Their fires, analysts later

said, were "ineffective" and "misdirected" at soft targets rather than

at the concealed gun positions ringing the island. But, as an element

in the cumulative psychological and physical toll on soldiers and

civilians alike, harassing fires of this nature were not

inconsiderable.

Over the next six weeks, the effort to degrade and

destroy the defenses and garrison of Tinian escalated. On 18 June, Navy

Task Force 52, commanded by Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, added its

guns to the mission. Air-strikes involving carrier planes and Army

P-47s were ordered. From 28 June until the Tinian landing on 24 July,

massed artillery battalions, firing from Saipan's southern shore, poured

thousands of tons of steel into the island. By mid-July, 13 battalions

were engaged in the mission, firing 160 guns—105s and Long Toms

155s—around the clock. The six battalions of the XXIV Corps

Artillery alone undertook 1,509 fire missions in that period, firing

24,536 rounds.

The precise effect of the artillery fires from Saipan

will never be known, but it is reasonable to assume there were many

scenes of the kind retired Brigadier General Frederick Karch described

in his oral history memoir. He was a major, serving as operations

officer for an artillery regiment—the 14th Marines—during the

Tinian campaign, and he recalled:

I remember going by a [Japanese] machine gun crew.

They had been trying to get a firing position and had been caught by the

artillery barrage, apparently, and they were laid out just like a school

solution, with each man carrying his particular portion of the gun

crew's equipment. And that was where they had died in a very fine

situation, except they were on the wrong side of the barrage.

During the two weeks from 26 June to 9 July, the

cruisers, Indianapolis, Birmingham, and Montpelier hit the

island daily. Their fires were supplemented in the week preceding Jig

Day (the D-Day designation for Tinian) by the battleships Colorado,

Tennessee, and California; the cruisers, Louisville,

Cleveland, and New Orleans; 16 destroyers, and dozens of

supporting vessels firing a variety of ordnance ranging from white

phosphorous aimed at wooded areas around the Japanese command post on

Mount Lasso to 40mm fire and rocket barrages by LCIs (landing craft,

infantry) directed at caves and other close-in targets.

|

|

|

By

the time the assault waves landed, most, if not all, Japanese beach

defense weapons had been destroyed by the preinvasion bombardments. This

Japanese navy-type 25mm machine cannon was knocked out before it could

disrupt the landings. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 87701

|

The Japanese, meanwhile, were preparing for their

counterattack. Because of shattered communications lines, it could not

be a coordinated operation. Units would act on their own under Colonel

Ogata's general order of 28 June to "destroy the enemy on beaches with

one blow, especially where time prevents quick movement of forces within

the island."

They had on the left or northern flank of the Marine

lines 600 to 1,000 naval troops at the Ushi Point air fields. Near Mount

Lasso, opposite the center of the Marine lines, were two battalions of

the 50th Infantry Regiment and a tank company, about 1,500 men

all told. On the west coast, facing the Marine right flank, were about

250 men from an infantry company of the 50th Regiment, a tank

detachment and an anti-tank squad.

|

|

Even

enemy weapons, such as this Japanese 120mm type 10 Naval dual-purpose

gun located not-too-far inland from the invasion beaches, was put out of

action, but not before it, and two 6-inch guns, hit the battleship

Colorado (BB 45) and destroyer Norman Scott (DD 690)

causing casualties before being destroyed. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

91349

|

|

|

Attacking Marines hold up their advance in the face of

an exploding Japanese ammunition dump after an attack by Navy planes

supporting the drive across Tinian. Note the trees bent over by the

force of shock waves caused by the eruption. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

87298

|

South of Mount Lasso, nearly six miles from the White

Beaches, was the Japanese Mobile Counterattack Force—a

900-man battalion of the 135th Infantry Regiment, equipped with

new rifles and demolition charges. Its journey toward the northwestern

beaches and the Marine lines was perilous. All movements in daylight

were under air surveillance and vulnerable to American fire power. But

the battalion set out under its commander—a Captain Izumi—and

was hit on several occasions by unobserved artillery and naval gunfire.

Izumi pushed on and got to his objective through skillful use of terrain

for for concealment. At 2230 he began probing the center of the Marine

line where the 2d Battalion, 24th Marines under Garretson was tied in

with the 3d Battalion under Chambers.

"While most of these Japanese crept along just

forward of the lines," Carl Hoffman wrote, ". . . a two-man

reconnaissance detail climbed up on a battered building forward of the

24th Marines and audaciously (or stupidly) commenced jotting notes

about, or drawing sketches of, the front lines. This impudent gesture

was rewarded with a thundering concentration of U.S. artillery

fire."

Chambers had a vivid memory of that night:

There was a big gully that ran from the southeast to

northwest and right into the western edge of our area. Anybody in their

right mind could have figured that if there was to be any

counterattacks, that gully would be used . . . .

During the night . . . my men were reporting that

they were hearing a lot of Japanese chattering down in the gully . . .

.

|

|

Amphibian tractors line up waiting to discharge their

Marine passengers on the beach. The almost complete devastation of

Japanese beachhead defenses, which was not entirely expected by the

Marines, permitted this peaceful combat landing. Department of Defense

Photo (USMC) 93379

|

|

|

While some Marines were deposited "feet dry" beyond the

ashore in the shallows from the amtracs which brought them shoreline of

the beaches, others had to land "feet wet" wading in from the attack

transports seen in the background. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

88088

|

They hit us about midnight in K company's area. They

hauled by hand a couple of 75mm howitzers with them and when they got

them up to where they could fire at us, they hit us very hard. I think K

company did a pretty damn good job but . . . about 150, 200 Japs managed

to push through [the 1,500 yards] to the beach area . . . .

When the Japs hit the rear areas, all the artillery

and machine guns started shooting like hell. Their fire was coming from

the rear and grazing right up over our heads . . . . In the meantime,

the enemy that hit L company was putting up a hell of a fight within 75

yards of where I was and there wasn't a damn thing I could do about

it.

Over in K company's area . . . was where the attack

really developed. That's where [Lt.] Mickey McGuire . . . had his 37mm

guns on the left flank and was firing canister. Two of my men were

manning a machine gun [Cpl Alfred J. Daigle and Pfc Orville H. Showers]

. . . . These two lads laid out in front of their machine gun a cone of

Jap bodies. There was a dead Jap officer in with them. Both of the boys

were dead.

|

|

Although frontline Marines appreciated the support of

the 1st and 2d Provisional Rocket Companies' truck-mounted 4.5-inch

rocket launchers, they always dreaded the period immediately following a

barrage. The dust and smoke thrown up at that time served as a perfect

aiming point for enemy artillery and mortars which soon followed. Notice

the flight of rockets in the upper left hand section of the

picture. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 92269

|

|

|

For

Tinian, as in the Marshall Islands and the Saipan and Guam operations,

DUKWs (amphibian trucks) were loaded with artillery pieces and

ammunition at the mount out area. At the objective beaches, they were

driven ashore right to the designated gun emplacements enabling the gun

crews to get their weapons laid in and firing quickly. Here, an A-frame

unloads a 75mm pack howitzer from an Army DUKW. Department of Defense

Photo (USMC) 87645

|

A Marine combat correspondent, described this

action:

[Showers and Daigle] held their fire until the

Japanese were 100 yards away, then opened up. The Japanese charged,

screaming, "Banzai," firing light machine guns and throwing hand

grenades. It seemed impossible that the two Marines—far ahead of

their own lines—could hold on . . . . The next morning they were

found slumped over their weapons, dead. No less than 251 Japanese bodies

were piled in front of them . . . . The Navy Cross was awarded

posthumously to Daigle and the Silver Star posthumously to Showers.

Just before daybreak, Chambers recalled, two tank

companies showed up, commanded by Major Robert I. Neiman. They "wanted

to get right at the enemy" and Chambers sent them off to an area held by

Companies K and L. Neiman returned in about a half hour and said, "You

don't need tanks. You need undertakers. I never saw so many dead

Japs."

Another large contingent of Japanese troops was

"stacked up" by the 75mm pack howitzer gunners of Battery D of the 14th

Marines, supported by the .50-caliber machine guns of Batteries E and F:

"They literally tore the Japanese . . . to pieces." Altogether about 600

Japanese were killed in their attack on the center.

|

|

On

the night of 24-25 July, a Japanese counterattack accompanied by tanks

failed completely with heavy losses. Here a Marine inspects the enemy

dead near a destroyed tank. Note the placement of the bullet holes in

the helmets in the ditch. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

91047

|

On the left flank, 1st Battalion, 24th Marines, came

under attack at 0200 from about 600 Special Naval Landing Force

troops out of the barracks at the Ushi Point airfields. Company A, hit

so hard it was reduced at one point to only 30 men with weapons, was

forced to draw reinforcements from engineers, corpsmen, communicators,

and members of the shore party. Illumination flares were fired over the

battlefield, allowing the Marines to use 37mm canister shells, machine

gun fire, and mortars to good effect. The fight continued until dawn

when medium tanks from the 4th Tank Battalion lumbered in to break up

the last attacking groups. At that point, many Japanese began using

their grenades to commit suicide.

As the sun rose, 476 Japanese bodies were counted in

this sector of the defensive crescent, most of them in front of the

Company A position.

The last enemy attack that night hit the right or

southern flank of the Marines beginning at 0330 when six Japanese tanks

(half of the Japanese tank force on Tinian) clattered up from the

direction of Tinian Town to attack the 23d Marines position. They were

met by fire from Marine artillery, anti-tank guns, bazookas, and small

arms. Lieutenant Jim Lucas, a professional reporter who enlisted in the

Marine Corps shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor and was

commissioned in the field, was there:

The three lead tanks broke through our wall of fire.

One began to glow blood-red, turned crazily on its tracks and careened

into a ditch. A second, mortally wounded, turned its machine guns on its

tormentors, firing into the ditches in a last desperate effort to fight

its way free. One hundred yards more and it stopped dead in its tracks.

The third tried frantically to turn and then retreat, but our men closed

in, literally blasting it apart . . . . Bazookas knocked out a fourth

tank with a direct hit which killed the driver. The rest of the crew

piled out of the turret screaming. The fifth tank, completely

surrounded, attempted to flee. Bazookas made short work of it. Another

hit set it afire and its crew was cremated.

The sixth tank was chased off, according to Colonel

Jones, by a Marine driving a jeep. Some appraisers of this action

believe only five tanks were involved. In any case, the destruction of

these tanks did not end the fight on the right flank. Infantry units of

the 50th Regiment continued to attack in the zone of 2d

Battalion, 23d Marines. They were repulsed and killed in great numbers,

largely through the effective use of 37mm anti-tank guns using canister

shot. In "the last hopeless moments of the assault," Hoffman wrote,

"some of the wounded Japanese destroyed themselves by detonating a

magnetic tank mine which produced a terrific blast."

From the Japanese standpoint, the night's work had

been a disaster: 1,241 bodies left on the battlefield; several hundred

more may have been carted away during the night. Fewer than 100 Marines

were wounded or killed. "The loss of these [Japanese] troops," the

historian Frank Hough has written:

. . . broke the back of the defense of Tinian. With

their communications shattered by sustained fire from Saipan and

increasing fire from Tinian itself . . . the survivors were capable of

only the weakest, most dazed sort of resistance . . . . Now and again

during the next seven days, small groups took advantage of the darkness

to [launch night attacks], but for the most part they simply withdrew in

no particular order until there remained nowhere to withdraw.

|

|

A

line of skirmishers was the formation normally used at Tinian even where

there was no enemy contact. A platoon from the 2d Marines pushes forward

while an observation plane (QY) circles overhead. High ground in the

distance is part of a long spine extending straight south from Mount

Lasso, an objective to be taken. Marine Corps Historical Collection

|

That was a common judgment after the Tinian battle

had ended. But at the time, according to the 4th Division intelligence

officer, Lieutenant Colonel Gooderham McCormick, a Marine Reserve

officer who later became mayor of Philadelphia, things were not so

clear: "We still believed [after the counterattack] the enemy capable of

a harder fight . . . and from day to day during our advance expected a

bitter fight that never materialized."

Nevertheless, a lot of hard work lay ahead. One of

the most demanding tasks was the simple but exhausting job of humping

through cane fields in terrific heat, humidity, and frequent monsoon

downpours, fearful not only of sniper fire, mines, or booby traps, but

fearful as well of fires that could sweep through the cane fields,

incinerating anyone in their path.

|