|

The Aircraft in the Conflict

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps were definitely at a

disadvantage when America entered World War II in December 1941. Besides

other areas, their frontline aircraft were well behind world

standards.

The Japanese did not suffer similarly, however, for

they were busy building up their arsenal as they sought sources of raw

materials they needed and were prepared to go to war to acquire. Besides

possessing what was the finest aerial torpedo in the world — the

Long Lance — they had the aircraft to deliver it. And they had

fighters to protect the bombers. Although the world initially refused to

believe how good Japanese aircraft and their pilots were, it wasn't long

after the attack on Pearl Harbor that reality seeped in.

|

|

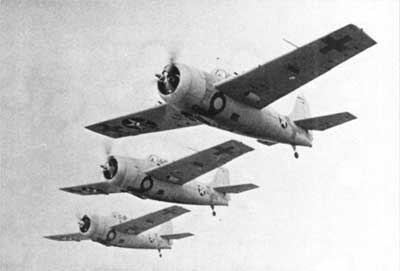

The

first production model of Grumman's stubby, little Wildcat was the

F4F-3, which carried four .50-caliber machine guns in the wings. Its

wings did not fold, unlike the -4 which added two more machine guns and

folding wings. These F4F-3s of VMF-121 carry prewar exercise

markings. Author's Collection

|

In many respects, the U.S. Army Air Force — it

had been the U.S. Army Air Corps until 20 June 1941 — and the Navy

and Marine Corps had the same problems in the first two years of the

war. The Army's top fighters were the Bell P-39 Airacobra and the

Curtiss P-40B/E Tomahawk/Kittyhawk. The Navy and Marine Corps' two

frontline fighters were the Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo and the Grumman

F4F-3/4 Wildcat during 1942.

Of these single-seaters, only the Army's P-40 and the

Navy's F4F achieved any measure of success against the Japanese in 1942.

The P-40's main attributes were its diving speed, which let it disengage

from a fight, and its ability to absorb punishment and still fly, a

confidence builder for its hard-pressed pilots. The Wildcat was also a

tough little fighter ("built like Grumman iron" was a popular

catch-phrase of the period), and had a devastating battery of four (for

the F4F-3) or six .50-caliber machine guns (for the F4F-4) and a fair

degree of maneuverability.

Both the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy also had

outstanding aircraft. The Army's primary fighter of the early war was

the Nakajima K.43 Hayabusa (Peregrine Falcon), a light, little aircraft,

with a slim, tapered fuselage and a bubble canopy.

The Navy's fighter came to symbolize the Japanese air

effort, even for the Japanese, themselves. The Mitsubishi Type "O"

Carrier Fighter (its official designation) was as much a trend-setting

design as was Britain's Spitfire or the American Corsair.

|

|

The Wildcat was a relatively small aircraft, as

were most of the pre war fighters throughout the world. The aircraft's

narrow gear track is shown to advantage in this ground view of a VMF-121

F4F-3.

|

However, as author Norman Franks wrote, the Allied

crews found that "the Japanese airmen were...far superior to the crude

stereotypes so disparaged by the popular press and cartoonists. And in a

Zero they were highly dangerous."

The hallmark of Japanese fighters had always been

superb maneuverability. Early biplanes — which had been developed

from British and French designs — set the pace. By the mid-1930s,

the Army and Navy had two world-class fighters, the Nakajima Ki.27 and

the Mitsubishi A5M series, respectively, both low-wing, fixed-gear

aircraft. The Ki.27 did have a modern enclosed cockpit, while the A5M's

cockpit was open (except for one variant that experimented with a canopy

which was soon discarded in service.) A major and fatal disadvantage of

most Japanese fighters was their light armament — usually a pair of

.30-caliber machine guns — and lack of armor, as well as their

great flammability.

When the Type "0" first flew in 1939, most Japanese

pilots were enthusiastic about the new fighter. It was fast, had

retractable landing gear and an enclosed cock pit, and carried two 20mm

cannon besides the two machine guns. Initial operational evaluation in

China in 1940 confirmed the aircraft's potential.

By the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor,

the A6M2 was the Imperial Navy's standard carrier fighter, and rapidly

replaced the older A5Ms still in service. As the A6M2 proved successful

in combat, it acquired its wartime nickname, "Zero," although the

Japanese rarely referred to it as such. The evocative name came from the

custom of designating aircraft in reference to the Japanese calendar.

Thus, since 1940 corresponded to the year 2600 in Japan, the fighter was

the Type "00" fighter, which was shortened to "0." The western press

picked up the designation and the name "Zero" was born.

|

|

This

A6M3 is taking off from Rabaul in 1943. Author's Collection

|

|

|

The

Zero's incredible maneuverability came at some expense from its top

speed. In an effort to increase the speed, the designers clipped the

folding wingtips from the carrier-based A6M2 and evolved the land-based

A6M3, Model 32. The pilots were not impressed with the speed increase

and the production run was short, the A6M3 reverting back to its span as

the Model 22. The type was originally called "Hap," after Gen Henry

"Hap" Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Force. Arnold was so angry at the

dubious honor that the name was quickly changed to Hamp. This Hamp is

shown in the Solomons during the

Guadalcanal campaign. Author's Collection

|

The fighter received another name in 1943 which was

almost as popular, especially among the American flight crews. A system

of first names referred to various enemy aircraft, in much the same way

that the postwar NATO system referred to Soviet and Chinese aircraft.

The Zero was tagged "Zeke," and the names were used interchangeably by

everyone, from flight crews to intelligence officers. (Other examples of

the system included "Claude" [A5M], "Betty" [Mitsubishi G4M bomber], and

"Oscar" [Ki.43].)

As discussed in the main text, the Navy and Marine

Corps Wildcats were sometimes initially hard-pressed to defend their

ships and fields against the large forces of Betty bombers and their

Zero escorts, which had ranges of 800 miles or more through the use of

drop tanks.

The Brewster Buffalo had little to show for its few

encounters with the Japanese, which is difficult to understand given the

type's early success during the Russo-Finnish War. The F2A-1, a lighter,

earlier model of the -3 which served with the Marines, was the standard

Finnish fighter plane. In its short combat career in American service,

the Brewster failed miserably.

Thus, the only fighter capable of meeting the

Japanese on anything approaching equal terms was the F4F, which was

fortunate because the Wildcat was really all that was available in those

dark days following Pearl Harbor. Retired Brigadier General Robert E.

Galer described the Wildcat as "very rugged and very mistreated (at

Guadalcanal)." He added:

|

|

Brewster's fat little F2A Buffalo is credited with a

dismal performance in American and British service, although the Finns

racked up a fine score against the Russians. This view of a Marine

Brewster shows the aptness of its popular name, which actually came from

the British. Its characteristic greenhouse canopy and main wheels tucked

snugly into its belly are also well shown. Author's Collection

|

|

|

The

A6M2-N float plane version of the Zero did fairly well, suffering only a

small loss in its legendary maneuverability. Top speed was somewhat

affected, however, and the aircraft's relatively light armament was a

detriment. Photo courtesy of Robert Mikesh

|

Full throttle, very few replacement parts, muddy

landing strips, battle damage, roughly repaired. We loved them. We did

not worry about flight characteristics except when senior officers

wanted to make them bombers as well as fighters.

The Japanese also operated a unique form of fighter.

Other combatants had tried to make seaplanes of existing designs. The

U.S. Navy had even hung floats on the Wildcat, which quickly became the

"Wildcatfish." The British had done it with the Spitfire. But the

resulting combination left much to be desired and sapped the original

design of much of its speed and maneuverability.

The Japanese, however, seeing the need for a

water-based fighter in the expanses of the Pacific, modified the A6M2

Zero, and came up with what was arguably the most successful water-based

fighter of the war, the A6M2-N, which was allocated the Allied codename

"Rufe."

|

|

A

good view of an early F4U-1 under construction in 1942. The massive

amount of wiring and piping for the aircraft's huge Pratt & Whitney

engine shows up here, as do the Corsair's gull wings. Author's

Collection

|

Manufactured by Mitsubishi's competitor, Nakajima,

float-Zeros served in such disparate climates as the Aleutians and the

Solomons. Although the floats bled off at least 40 mph from the

land-based version's top speed, they seemed to have had only a minor

effect on its original maneuverability; the Rule acquired the same

respect as its sire.

While the F4F and P-40 (along with the luckless P-39)

held the line in the Pacific, other, newer designs were leaving

production lines, and none too soon. The two best newcomers were the

Army's Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the Navy's Vought F4U Corsair. The

P-38 quickly captured the headlines and public interest with its unique

twin-boomed, twin-engine layout. It soon developed into a long-range

escort, and served in the Pacific as well as Europe.

|

|

The

Marine pilot of this F4U-1, Lt Donald Balch, contemplates his good

fortune by the damaged tail of his fighter. The Corsair was a relatively

tough aircraft, but like any plane, damage to vital portions of its

controls or powerplant could prove fatal. Author's Collection

|

The Corsair was originally intended to fly from air

craft carriers, but its high landing speed, long nose that obliterated

the pilot's view forward during the landing approach, and its tendency

to bounce, banished the big fighter from American flight decks for a

while. The British, however, modified the aircraft, mainly by clip ping

its wings, and flew it from their small decks.

Deprived of its new carrier fighter — having

settled on the new Grumman F6F Hellcat as its main carrier fighter

— the Navy offered the F4U to the Marines. They took the first

squadrons to the Solomons, and after a few disappointing first missions,

they made the gull-winged fighter their own, eventually even flying it

from the small decks of Navy escort carriers in the later stages of the

war.

|

|

This

"bird-cage" Corsair is landing at Espiritu Santo in September 1943. The

aircraft's paint is well-weathered and its main gear tires are "dusty"

from the coral runways of the area. National Archives 80G-54284

|

|

|

1stLt Rolland N. Rinabarger of VMF-214 in his early

F4U-1 Corsair at Espiritu Santo in September 1943. Badly shot up by

Zeros during an early mission to Kahili only two weeks after this photo

was taken, Lt Rinabarger returned to the States for lengthy treatment.

He was still in California when the war ended. The national insignia on

his Corsair is outlined in red, a short-lived attempt to regain that

color from the prewar marking after the red circle was deleted following

Pearl Harbor to avoid confusion with the Japanese "meatball." Even this

small amount of red was deceptive, however, and by mid-1944, it was gone

from the insignia again. Note the large mud spray on the aft under

fuselage. National Archives 80G-54279

|

Besides the two main fighters, the Army's Oscar and

the Navy's Zeke and its floatplane derivative, the Rufe, the Japanese

flew a wide assortment of aircraft, including land-based bombers, such

as the Mitsubishi G4M (codenamed Betty) and Ki.21 (Sally). Carrier-based

bombers included the Aichi D3A divebomber (the Val) which saw

considerable service during the first three years of the war, and its

stablemate, the torpedo bomber from Nakajima, the B5N (Kate), one of the

most capable torpedo-carriers of the first half of the war. The Marine

Corps squadrons in the Solomons regularly encountered these aircraft.

First Lieutenant James Swett's two engagements on 7 April 1943 netted

the young Wildcat pilot seven Vals, and the Medal of Honor.

Although early wartime propaganda ridiculed Japanese

aircraft and their pilots, returning Allied aviators told different

stories, although the details of their experiences were kept classified.

Each side's culture provided the basis for their aircraft design

philosophies. Eventually, the Japanese were overwhelmed by American

technology and numerical superiority. However, for the important first

18 months of the Pacific war, they had the best. But, as was also the

case in the European theaters, a series of misfortunes, coincidences, a

lack of understanding by leaders, as well as the drain of prolonged

combat, finally allowed the Americans and their Allies to overcome the

enemy's initial edge.

|

|

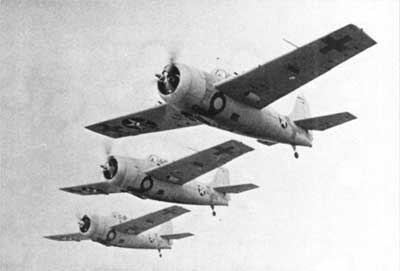

Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers, perhaps during the

Solomons campaign. Probably the best Japanese land-based bomber in the

war's first two years, the G4M series enjoyed a long range, but could

burst into flames under attack, much to the chagrin of its crews. The

type flew as a suicide aircraft, and finally, painted white with green

crosses, carried surrender teams to various sites. Photo courtesy Robert

Mikesh

|

|