|

Japanese Pilots in the Solomons Air War

The stereotypical picture of a small, emaciated

Japanese pilot , wearing glasses whose lenses were the thickness of the

bottoms of Coke bottles, grasping the stick of his bamboo-and-rice-paper

airplane (the design was probably stolen from the U.S., too) did not

persist for long after the war began. The first American aircrews to

return from combat knew that they had faced some of the world's most

experienced combat pilots equipped with some pretty impressive

airplanes.

|

|

A

rebuilt late-model Zero shows off the clean lines of the A6M series,

which changed little during the production run of more than 10,000

fighters. Author's Collection

|

Certainly, Japanese society was completely alien to

most Americans. Adherence to ancestral codes of honor and a national

history — one of constant internal, localized strife where personal

weakness was not tolerated, especially in the Samurai class of

professional warriors — did not permit the individual Japanese

soldier to surrender even in the face of overwhelming odds.

|

|

Newly commissioned Ens Junichi Sasai in May 1941.

Author's

Collection

|

This capability did not come by accident. Japanese

training was tough. In some respects, it went far beyond the legendary

limits of even U.S. Marine Corps boot training. However, as the war

turned against them, the Japanese relaxed their stringent prewar

requirements and mass-produced pilots to replace the veterans who were

lost at Midway and in the Solomons. For instance, before the war, pilots

learned navigation and how to pack a parachute. After 1942, these

subjects were eliminated from training to save time.

Young men who were accepted for flight training were

subjected to an excruciating preflight indoctrination into military

life. Their instructors — mostly enlisted — were literally

their rulers, with nearly life-or-death control of the recruits'

existence. After surviving the physical training, the recruits began

flight training where the rigors of their preflight classes were

maintained. By the time Japanese troops evacuated Guadalcanal in

February 1943, however, their edge had begun wearing thin as they had

lost many of their most experienced pilots and flight commanders, along

with their aircraft.

The failed Japanese adventure at Midway in June 1942,

as well as the heavy losses in the almost daily combat over Guadalcanal

and the Solomons deprived them of irreplaceable talent. Even the most

experienced pilots eventually came up against a losing roll of the

dice.

As noted in the main text, Japanese aces such as

Sakai, Sasai, and Ota were invalided out of combat, or eventually

killed. Rotation of pilots out of the war zone was a system employed

neither by the Japanese nor the Germans, as a matter of fact. As several

surviving Axis aces have noted in their memoirs, they flew until they

couldn't. Indeed many Japanese and German aces flew until 1945 — if

they were lucky enough to survive — accumulating incredible numbers

of sorties and combat hours, as well as high scores which doubled and

tripled the final tallies of their American counterparts.

Unfortunately, Japanese records are not as complete

as Allied histories, perhaps because of the tremendous damage and

confusion wrought by the U.S. strategic bombing during the last year of

the war. Thus, certainly Japanese scores are not as firm as they are for

Allied aviators.

In the popularly accepted sense, the Japanese did not

have "aces." Those pilots who achieved high scores were referred to as

Gekitsui-O (Shoot-Down Kings). A pilot's report of his successes was

taken at face value, without a confirmation system such as required by

the Allies. Without medals or formal recognition, it was believed that

there was little need for self-promotion. Fighters did not have gun

cameras, either. Japanese air strategy was to inflict as much damage as

possible without worrying about confirming a kill. (This outwardly

cavalier attitude about claiming victories is somewhat suspect since

many Zeros carried large "scoreboards" on their tails and fuselages.

These markings might have been attributed to the aircraft rather than to

a specific pilot.)

|

|

A

lineup of A6M2 Zeros at Buin in 1943. By this time, the heavy combat

over Guadalcanal had been replaced by engagements with Marine Corsairs

over the approaches to Bougainville. Japanese Navy aircraft occasionally

flew from land bases, as these Zeros, although they are actually

assigned to the carrier Zuikaku. Author's Collection

|

The Aces

Although the men in the Zeros were probably much like

— at least in temperament — Marine Wildcat and Corsair pilots

they opposed, the Imperial Japanese Navy pilots had an advantage: many

of them had been flying combat for perhaps a year — maybe longer

— before meeting the untried American aviators over Guadalcanal in

August 1942. Saburo Sakai was severely wounded during an engagement with

U.S. Navy SBDs on the opening day of the invasion. He returned to Japan

with about 60 kills to his credit. Actually, because he was so badly

wounded early in the Guadalcanal fighting, Sakai never got a chance to

engage Marine Corps pilots. They were still in transit to the Solomons

two weeks after Sakai had been invalided home. (His commonly accepted

final score of 64 is only a best guess, even by his own logbook.)

|

|

Enlisted pilots of the Tainan Kokutai pose at Rabaul in

1942. Several of these aviators would be among the top Japanese aces,

including Saburo Sakai (middle row, second from left), and Hiroyoshi

Nishizawa (standing, first on left). Author's Collection

|

After graduating from flight training, Sakai joined a

squadron in China flying Mitsubishi Type 96 fighters, small,

open-cockpit, fixed-landing-gear fighters. As a third-class petty

officer, Sakai shot down a Russian built SB-3 bomber in October 1939. He

later joined the Tainan Kokutai (Tainan air wing), which would be come

one of the Navy's premier fighter units, and participated in the Pacific

war's opening actions in the Philippines.

A colorful personality, Sakai was also a dedicated

flight leader. He never lost a wingman in combat, and also tried to pass

on his hard-won expertise to more junior pilots. After a particularly

unsuccessful mission in April 1942, where his flight failed to bring

down a single American bomber from a flight of seven Martin B-26

Marauders, he sternly lectured his pilots about maintaining flight

discipline instead of hurling them selves against their foes. His words

had great effect — Sakai was respected by subordinates and

superiors alike — and his men soon formed a well-working unit,

responsible for many kills in the early months of the Pacific war.

Typically, Junichi Sasai, a lieutenant, junior grade,

and one of Sakai's young aces with 27 confirmed kills, was posthumously

promoted two grades to lieutenant commander. This practice was common

for those Japanese aviators with proven records, or high scores, who

were killed during the war. Japan was unique among all the combatants

during the war in that it had no regular or defined system of awards,

except for occasional inclusion in war news — what the British

might call being "mentioned in dispatches."

This somewhat frustrating lack of recognition was

described by Masatake Okumiya, a Navy fighter commander, in his classic

book Zero! (with Jiro Horikoshi). Describing a meeting with

senior officers, he asked them, "Why in the name of heaven does

Headquarters delay so long in according our combat men the honors they

deserve?. . .Our Navy does absolutely nothing to recognize its

heroes..."

LCdr

Tadashi Nakajima, who led the Tainan Air Group, was typical of the more

senior aviators. His responsibilities were largely administrative but he

tried to fly missions whenever his schedule permitted, usually with

unproductive results. He led several of the early missions over

Guadalcanal and survived to lead a Shiden unit in 1944. It is doubtful

that Nakajima scored more than 2 or 3 kills. Author's Collection

|

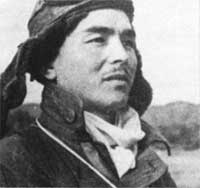

Lt

(j.g.) Junichi Sasai of the Tainan Air Group. This 1942 photo shows the

young combat leader, of such men as Sakai and Nishizawa. shortly before

his death over Guadalcanal. Author's Collection

|

Occasionally, senior officers would give gifts, such

as ceremonial swords, to those pilots who had performed great services.

And sometimes, superiors would try to buck the unbending system without

much success. Saburo Sakai described one instance in June 1942 where the

captain in charge of his wing summoned him and Lieutenant Sasai to his

quarters.

Dejectedly, the captain told his two pilots how he

had asked Tokyo to recognize them for their great accomplishments.

"...Tokyo is adamant about making any changes at this time," he said.

"They have refused even to award a medal or to promote in rank." The

captain's deputy commander then said how the captain had asked that

Sasai be promoted to commander — an incredible jump of three grades

— and that Sakai be commissioned as an ensign.

Perhaps one of the most enigmatic, yet enduring,

personalities of the Zero pilots was the man who is generally

acknowledged to be the top-scoring Japanese ace, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa.

Saburo Sakai described him as "tall and lanky for a Japanese, nearly

five feet, eight inches in height," and possessing "almost supernatural

vision."

|

|

These A6M3s are from the Tainan Air Group, and several

sources have identified aircraft 106 as being flown by top ace

Nishizawa. Typically, these fighters carry a single centerline fuel

tank. The Zero's range was phenomenal, sometimes extending to nearly

1,600 miles, making for a very long flight for its exhausted

pilots. Photo courtesy of Robert Mikesh

|

Nishizawa kept himself usually aloof, enjoying a

detached but respected status as he rolled up an impressive victory

tally through the Solomons campaign. He was eventually promoted to

warrant officer in November 1943. Like a few other high-scoring aces,

Nishizawa met death in an unexpected manner in the Philippines. He was

shot down while riding as a passenger in a bomber used to transport him

to another base to ferry a Zero in late October 1944. In keeping with

the established tradition, Nishizawa was posthumously promoted two ranks

to lieutenant junior grade. His score has been variously given as 102,

103, and as high as 150.

However, the currently accepted total for him is

87.

Henry Sakaida, a well-known authority on Japanese

pilots in World War II, wrote:

No Japanese pilot ever scored more than 100

victories! In fact, Nishizawa entered combat in 1942 and his period of

active duty was around 18 months. On the other hand, Lieutenant junior

grade Tetsuo Iwamoto fought from 1938 until the end of the war. If there

is a top Navy ace, it's him.

Iwamoto claimed 202 victories, many of which were

against U.S. Marine Corps aircraft, including 142 at Rabaul. I don't

believe his claims are accurate, but I don't believe Nishizawa's total

of 87, either. (I might believe 30.) Among Iwamoto's claims were 48

Corsairs and 48 SBDs! His actual score might be around 80.

Several of Sho-ichi Sugita's kills — which are

informally reckoned to total 70 — were Marine aircraft. He was

barely 19 when he first saw combat in the Solomons. (He had flown at

Midway but saw little of the fighting.) Flying from Buin on the southern

tip of Bougainville. he first scored on 1 December 1942, against a USAAF

B-17. Sugita was one of the six Zero escort pilots that watched as P-38s

shot down Admiral Yamamoto's Betty on 18 April 1943. There was little

they could do to alert the bombers carrying the admiral and his staff

since their Zeros' primitive radios had been taken out to save

weight.

The problem of keeping accurate records probably came

from the directive issued in June 1943 by Tokyo forbidding the recording

of individual records, the better to foster teamwork in the seemingly

once-invincible Zero squadrons. Prior to the directive, Japanese Zero

pilots were the epitome of the hunter-pilots personified by the World

War I German ace, Baron Manfred von Richthofen. The Japanese Navy pilots

roamed where they wished and attacked when they wanted, assured in the

superiority of their fighters.

Occasionally, discipline would disappear as flight

leaders dove into Allied bomber formations, their wingmen hugging their

tails as they attacked with their maneuverable Zeros, seemingly

simulating their Samurai role models whose expertise with swords is

legendary.

Petty Officer Hiroyoshi Nishizawa at Lae, New Guinea, in

1942. Usually considered the top Japanese ace, Navy or Army. A

definitive total will probably never be determined. Nishizawa died while

flying as a passenger in a transport headed for the Philippines in

October 1944. The transport was caught by American Navy Hellcats, and

Lt(j.g.) Harold Newell shot it down. Author's Collection

|

Petty Officer Sadamu Komachi flew throughout the Pacific

War, from Pearl Harbor to the Solomons, from Bougainville to the defense

of the Home Islands. His final score was 18. Photo courtesy of Henry

Sakaida

|

Most of the Japanese aces, and most of the

rank-and-file pilots, were enlisted petty officers. In fact, no other

combatant nation had so many enlisted fighter pilots. The U.S. Navy and

Marine Corps had a relatively few enlisted pilots who flew in combat in

World War II and for a short time in Korea. Britain and Germany had a

considerable number of enlisted aviators without whose services they

could not have maintained the momentum of their respective

campaigns.

However, the Japanese officer corps was relatively

small, and the number of those commissioned pilots serving as combat

flight commanders was even smaller. Thus, the main task of fighting the

growing Allied air threat in the Pacific fell to dedicated enlisted

pilots, many of them barely out of their teens.

During a recent interview, Saburo Sakai shed light on

the role of Japanese officer-pilots. He said:

They did fight, but generally, they were not very

good because they were inexperienced. In my group, it would be the

enlisted pilots that would first spot the enemy. The first one to see

the enemy would lead and signal the others to follow. And the officer

pilot would be back there, wondering where everyone went! In this sense,

it was the enlisted pilots who led, not the officers.

|