|

TIME OF THE ACES: Marine Pilots in the Solomons

by Commander Peter B. Mersky, U.S. Naval Reserve

Guadalcanal: The Beginning of the Long Road Back

Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 23, the initial air unit

participating in the Guadalcanal operation, was assigned the mission of

supporting the ground operations of the 1st Marine Division as well the

air defense of the island once the landing had been made. MAG-23

included VMF-223 and -224, and VMSB-231 and -232. The fighter squadrons

flew the F4F-4, the Grumann Wildcat with folding wings and six

wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns. The two VMSBs flew the Douglas

SBD-3 Dauntless dive-bomber. Another fighter squadron, VMF-212, under

Major Harold W. Bauer, was on the island of Efate in the New Hebrides,

while MAG-23 headquarters had yet to sail from Hawaii by the time

Marines hit the beaches on 7 August 1942. The first contingent of MAG-23

— VMF-223 and VMSB-232 — left Hawaii on board the escort

carrier USS Long Island (CVE 1). On 20 August, 200 miles from

Guadalcanal, the two squadrons launched toward their new home. VMF-224

(Captain Robert E. Galer) and VMSB-231 (Major Leo R. Smith) followed in

the aircraft transports USS Kitty Hawk (APV 1) and USS

Hammondsport (APV 2), and flew on to the island on 30 August.

While en route toward the launch point for Guadalcanal, Captain Smith

wisely decided to trade eight of his less experienced junior pilots for

eight pilots of VMF-212 who had more flight time and training in the F4F

than had Smith's fledglings.

|

|

The

Douglas SBD Dauntless divebomber fought in nearly every theater, flying

with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, as well as the U.S. Army (as the

A-24 Banshee). The SBD made its reputation in the Pacific, especially at

Midway and Guadalcanal. Author's Collection

|

The newly arrived squadrons barely had time to get

settled before they were in heavy action. Early on the 21st, the

Japanese sent a 900-man force to attack Henderson Field, named after

Major Lofton R. Henderson, a dive-bomber pilot killed at Midway. Around

mid-day, Captain Smith was leading a four-plane patrol north of Savo

Island heading to ward the Russell Islands with Second Lieutenants Noyes

McLennan and Charles H. Kendrick, and Technical Sergeant John Lindley.

The two lieutenants had 16 days of operational flight training in F4Fs,

and Lindley had been through ACTG, the Aircraft Carrier Training Group,

which, as part of its training syllabus, gave tyro pilots indoctrination

into fighter tactics.

Beyond Savo, six Zeros came straight at them from the

north, with an altitude advantage of 500 feet. Smith recognized the

Zeros immediately, although neither he nor any of the other three pilots

had ever seen one before. He turned his flight toward them and the Zeros

headed toward the F4Fs.

It was hard to say just what happened next except

that the Zero Smith was shooting at pulled up and he shot fairly well

into the belly of the enemy plane as it went by, only to find that now

he had two Zeros on his tail. Captain Smith dove toward Henderson Field

and the Japs broke away.

|

|

Members of VMF-224 pose by one of their fighters on

Guadalcanal in mid-September 1942. Rear row, left to right: 2dLt George

L. Hollowell, SSgt Clifford D. Garrabrant, 2dLt Robert A Jefferies, Jr.,

2dLt Allan M. Johnson, 2dLt Matthew H. Kennedy, 2dLt harles H. Kunz,

2dLt Dean S. Hartley, Jr., MG William R. Fuller. Front row: 2dLt Robert

M. D'Arcy, Capt Stanley S. Nicolay, Maj John F Dobbin, Maj Robert E.

Galer, Maj Kirk Armistead, Capt Dale D. Irwin, 2dLt Howard L. Walter,

2dLt Gordon E. Thompson. All in this picture are pilots except MG

Fuller, who was the Engineering Officer. Lt Thompson was reported

missing in action on 31 August 1942. Photo courtesy of BGen Robert E.

Galer

|

Minutes later, the Zero Captain Smith shot became

VMF-223's first kill when it crashed into the water just off Savo

Island. Smith's plane had some bullet holes but was flying alright. Two

F4Fs joined on him. They looked back and it appeared that the Zeros were

in a dogfight near Savo. The Marines thought they were ganging up on

Sergeant Lindley so they went back to help him, but found that there was

no F4F, just five Zeros acting like they were fighting.

The three Marines then got into another dogfight and

the Zeros shot them up some more. Lindley and Kendrick got back to

Henderson and made dead-stick landings. Lindley was burned and blinded

by hot oil when his oil tank was shattered and landed wheels up.

Kendrick's oil line was shot away and he crash-landed. His airplane

never flew again. It took eight days before Smith's plane was patched up

enough to fly once again. Repairs on the fourth plane required 10 days.

Only 15 of the 19 F4Fs were flyable after their first day of action from

Henderson Field.

Marion Carl, now assigned to VMF-223, shot down three

Japanese aircraft on 24 August to become the Marine Corps' first ace.

Carl added two more kills on the 26th. The young fighter pilot found

himself in competition with his squadron commander, as John Smith also

began accumulating kills with regularity.

Capt

Henry T. Elrod, a Wildcat pilot with VMF-211, earned what is

chronologically the first Marine Corps — but not the first actually

awarded — Medal of Honor for World War II. His exploits during the

defense of Wake Island were not known until after the war. After his

squadron's aircraft were all destroyed, Capt Elrod fought on the ground

and was finally killed by a Japanese rifleman. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

26044

|

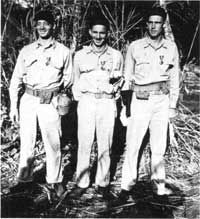

Three personalities of the Cactus Air Force pose after

receiving the Navy Cross from Adm Nimitz on 30 September 1942. From

left: Maj John L. Smith, Maj Robert E. Galer, and Capt Marion E.

Carl. Photo courtesy or Capt Stanley S. Nicolay

|

|

'CUB One' at Guadalcanal

On 8 August 1942, U.S. Marines captured a nearly

completed enemy airstrip on Guadalcanal, which would prove critical to

the success of the island campaign. It was essential that the airstrip

become operational as quickly as possible, not only to contest enemy

aircraft in the skies over Guadalcanal, but also to ensure that badly

needed supplies could be flown in and wounded Marines flown out. As it

turned out, Henderson Field also proved to be a safe haven for Navy

planes whose carriers had been sunk or badly damaged.

A Marine fighter squadron (VMF-223) and a Marine dive

bomber squadron (VMSB-232) were expected to arrive on Guadalcanal around

16 August. Unfortunately, Marine aviation ground crews scheduled to

accompany the two squadrons to Guadalcanal were still in Hawaii, and

would not arrive on the island for nearly two weeks. Aircraft ground

crews were urgently needed to service the two Marine squadrons upon

their arrival.

The nearest aircraft ground crews to Guadalcanal were

not Marines, but 450 Navy personnel of a unit known as CUB One, an

advanced base unit consisting of the personnel and material necessary

for the establishment of a medium-sized advanced fuel and supply base.

CUB One had only recently arrived at Espiritu Santo in the New

Hebrides.

On 13 August, Admiral John S. McCain ordered Marine

Major Charles H. "Fog" Hayes, executive officer of Marine Observation

Squadron 251, to proceed to Guadalcanal with 120 men of CUB One to

assist Marine engineers in completing the airfield (recently named

Henderson Field in honor of a Marine pilot killed in the Battle of

Midway), and to serve as ground crews for the Marine fighters and dive

bombers scheduled to arrive within a few days. Navy Ensign George W.

Polk was in command of the 120-man unit, and was briefed by Major Hayes

concerning the unit's critical mission. (After the war, Polk became a

noted newsman for the Columbia Broadcasting System, and was murdered by

terrorists during the Greek Civil War. A prestigious journalism award

was established and named in his honor).

Utilizing four destroyer transports of World War I

vintage, the 120-man contingent from CUB One departed Espiritu Santo on

the evening of 13 August. The total supply carried northward by the four

transports included 400 drums of aviation gasoline, 32 drums of

lubricant, 282 bombs (100 to 500 pounders), belted ammunition, a variety

of tools, and critically needed spare parts.

The echelon arrived at Guadalcanal on the evening of

15 August, unloaded its passengers and supplies, and began assisting

Marine engineers the following morning on increasing the length of

Henderson Field. In spite of daily raids by Japanese aircraft, the

arduous work continued, and on 19 August, the airstrip was completed.

CUB One personnel also installed and manned an air-raid warning system

in the famous "Pagoda," the Japanese-built control tower.

|

|

Allied air operations in the Solomons were controlled

from the "Pagoda," built by the Japanese and rehabilitated by the men of

CUB One. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 51812

|

On 20 August, 19 planes of VMF-223 and 12 dive

bombers of VMSB-232 were launched from the escort carrier Long

Island and arrived safely at Henderson Field. The Marine pilots were

quickly put into action over the skies of Guadalcanal in combat

operations against enemy aircraft.

The men of CUB One performed heroics in servicing the

newly arrived Marine fighters and bombers. Few tools existed or had yet

arrived to perform many of the aircraft servicing jobs to which CUB One

was assigned. It was necessary to fuel the Marine aircraft from

55-gallon drums of gasoline. As there were no fuel pumps on the island,

the drums had to be man-handled and tipped into the wing tanks of the

SBDs and the fuselage tanks of the F4F fighters. To do this, CUB One

personnel stood precariously on the slippery wings of the aircraft and

sloshed the gasoline from the heavy drums into the aircraft's gas tanks.

The men used a make-shift funnel made from palm-log lumber.

Bomb carts or hoists were also at a premium during

the early days of the Guadalcanal campaign, so aircraft bombs had to be

raised by hand to the SBD drop brackets, as the exhausted, straining men

wallowed in the mud beneath the airplanes.

No automatic belting machines were available at this

time as well, so that the .50-caliber ammunition for the four guns on

each fighter had to be hand-belted one round at a time by the men of CUB

One. The gunners on the dive bombers loaded their ammunition by the same

laborious method.

The dedicated personnel of CUB One performed these

feats for 12 days before Marine squadron ground crews arrived with the

proper equipment to service the aircraft. The crucial support provided

by CUB One was instrumental to the success of the "Cactus Air Force" on

Guadalcanal.

Like their Marine counterparts, the personnel of CUB

One suffered from malaria, dengue fever, sleepless nights, and the

ever-present shortage of food, clothing, and supplies. They would remain

on Guadalcanal, performing their duties in an exemplary manner, until

relieved on 5 February 1943. CUB One richly earned the Presidential Unit

Citation awarded to the unit for its gallant participation in the

Guadalcanal campaign.

—Arvil L. Jones with Robert V. Aquilina

|

|