| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

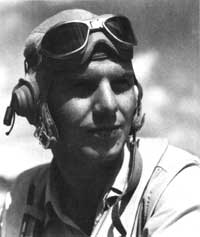

TIME OF THE ACES: Marine Pilots in the Solomons by Commander Peter B. Mersky, U.S. Naval Reserve The One and Only 'Pappy' Every one of the Corps' aces had special qualities that set him apart from his squadron mates. Flying and shooting skills, tenacity, aggressiveness, and a generous share of luck — the aces had these in abundance. One man probably had more than his share of these qualities, and that was the legendary "Pappy" Boyington.

A native of Idaho, Gregory Boyington went through flight training as a Marine Aviation Cadet, earning a reputation for irreverence and high jinks that did not go down well with his superiors. His thirst for adventure, as well as his accumulated financial debts, led him to resign his commission as a first lieutenant and join the American Volunteer Group (AVG), better known as the Flying Tigers. Like other service pilots who joined the AVG, he first resigned his commission and this letter was then put in a safe to be redeemed and torn up when he rejoined the Marine Corps. Boyington claimed to have shot down six Japanese aircraft while with the Flying Tigers. However, AVG records were poorly kept, and were lost in air raids. To compound the problem, the U.S. Air Force does not officially recognize the kills made by the AVG, even though the Tigers were eventually absorbed into the Fourteenth Air Force, led by Major General Claire Chennault. Thus, the best confirmation that can be obtained on Boyington's record with the AVG is that he scored 3.5 kills. Whatever today's accounts show, Boyington returned to the U.S. claiming to be one of America's first aces. He was perhaps the first Marine aviator to have flown in combat against the Japanese, though, and he felt he would easily regain his commission in the Marine Corps. To his frustration, no one in any service seemed to want him. His reputation was well known and this made his reception not exactly open armed. Boyington finally telegrammed his qualifications to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, and as a result, found himself back in the Marine Corps on active duty as a Reserve major. He deployed as executive officer of VMF-122 from the West Coast to the Solomons. He was based at Espiritu Santo, initially flying squadron training, non-combat missions. He deployed for a short but inactive tour at Guadalcanal in March 1943, and after the squadron was withdrawn, he relieved Major Elmer Brackett as commanding officer in April 1943. His first command tour was disappointing. He eventually landed in VMF-112. which he commanded for three weeks in the rear area. Prior to forward deployment, he broke his leg while wrestling and was hospitalized.

Boyington got another chance and took command of a reconstituted VMF-214. The original unit had returned from a combat tour, during which it had lost its commanding officer, Major William Pace. When the squadron returned from a short rest and recreation tour in Australia, the decision was made to reorganize the unit because the squadron did not have a full complement of combat-ready pilots. Thus, the squadron number went to a newly organized squadron under Major Boyington. In his illuminating wartime memoir, Once They Were Eagles: The Men of the Black Sheep Squadron, the squadron intelligence officer, First Lieutenant Frank Walton, described how Boyington got the new squadron command:

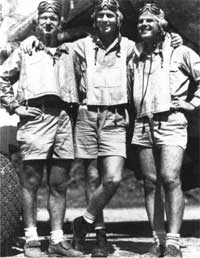

Much has been written about Boyington and his squadron. At 31, Boyington was older than his 22-year-old lieutenants. His men called him "Gramps" or "Pappy." In prewar days, he was called "Rats," after the Russian-born actor, Gregory Ratoff. The squadron wanted to call themselves the alliterative "Boyington's Bastards," but 1940s sensitivities would not allow such language. They decided on the more evocative "Black Sheep." The popular image of VMF-214 as a collection of malcontents and ne'er-do-wells is not at all accurate. The television program of the late 1970s did nothing to dispel this inaccurate impression. In truth, Pappy's squadron was much like any other fighter squadron, with a cross-section of people of varying capabilities and experience. The two things that welded the new squadron into such a fearsome fighting unit was its new mount, the F4U-1 Corsair, and its indomitable leader.

Boyington took his squadron to Munda on New Georgia in September. On the 16th, the Black Sheep flew their first mission, a bomber escort to Ballale, a Japanese airfield on a small island about five miles southeast of Bougainville. The mission turned into a free-for-all as about 40 Zeros descended on the bombers. Boyington downed a Zero for his squadron's first kill. He quickly added four more. Six other Black Sheep scored kills. It was an auspicious debut, marred only by the loss of one -214 pilot, Captain Robert T. Ewing. The following weeks were filled with continuous action. Boyington and his squadron rampaged through the enemy formations, whether the Marine Corsairs were escorting bombers, or making pure fighter sweeps. The frustrated Japanese tried to lure Pappy into several traps, but the pugnacious ace taunted them over the radio, challenging them to come and get him.

By mid-December 1943, VMF-214, along with the other Allied fighter squadrons, began mounting large fighter sweeps staged through the new fighter strip at Torokina Point on Bougainville. Author Barrett Tillman described the state of affairs in the area at the end of December 1943:

This strategy was fine, except that Boyington was beginning to feel the pressure that being a top ace seemed to bring. People kept wondering when Pappy would achieve, then break, the magic number of 26, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker's score in World War I. Joe Foss had already equalled the early ace's total, but was now out of action. Boyington scored four kills on 23 December 1943, bringing his tally to 24. Boyington was certainly feeling the pressure to break Rickenbacker's 25-year-old record. Boyington's intelligence officer, First Lieutenant Frank Walton, wrote of his tenseness and quick flareups when pressed about when and by how much he would surpass the magic 26. A few days before his final mission, Boyington reacted to a persistent public affairs officer. "Sure, I'd like to break the record," said Boyington. "Who wouldn't? I'd like to get 40 if I could. The more we can shoot down here, the fewer there'll be up the line to stop us." Later that night, Boyington told Walton, "Christ, I don't care if I break the record or not, if they'd just leave me alone." Walton told his skipper the squadron was behind him and that he was probably in the best position he'd ever be in to break the record.

"You'll never have another chance," Walton said. "It's now or never." "Yes," Boyington agreed, "I guess you're right." Like a melodrama, however, Boyington's life now seemed to revolve around raising his score. Even those devoted members of his squadron could not help wondering — if only to cheer their squadron commander on — when he would do it. Pappy's agony was about to come to a crashing halt. He got a single kill on 27 December during a huge fight against 60 Zeros. But, after taking off on a mission against Rabaul on 2 January 1944, at the head of 56 Navy and Marine fighters, Boyington had problems with his Corsair's engine. He returned without adding to his score. The following day, he launched at the head of another sweep staging through Bougainville. By late morning, other VMF-214 pilots returned with the news that Boyington had, indeed, been in action. When they last saw him, Pappy had already disposed of one Zero, and together with his wingman, Captain George M. Ashmun, was hot on the tails of other victims. The initial happy anticipation turned to apprehension as the day wore on and neither Pappy nor Ashmun returned. By the afternoon, without word from other bases, the squadron had to face the unthinkable: Boyington was missing. The Black Sheep mounted patrols to look for their leader, but within a few days, they had to admit that Pappy was not coming back.

In fact, Boyington and his wingman had been shot down after Pappy had bagged three more Zeros, thus bringing his claimed total to 28, breaking the Rickenbacker tally, and establishing Boyington as the top-scoring Marine ace of the war, and, for that matter, of all time. However, these final victories were unknown until Boyington's return from a Japanese prison camp in 1945. Boyington's last two kills were thus unconfirmed. The only one who could have seen Pappy's victories was his wingman, Captain Ashmun, shot down along with his skipper. While there is no reason to doubt his claims, the strict rules of verifying kills were apparently relaxed for the returning hero when he was recovered from a prisoner of war camp after the war.

Pappy and his wingman had been overwhelmed by a swarm of Zeros and had to bail out of their faltering Corsairs near Cape St. George on New Ireland. Captain Ashmun was never recovered, but Boyington was retrieved by a Japanese submarine after being strafed by the vengeful Zeros that had just shot him down. Boyington spent the next 20 months as a prisoner of war, although no one in the U.S. knew it until after V-J Day. He endured torture and beatings during interrogations, and was finally rescued when someone painted "Boyington Here!" on the roof of his prison barracks. Aircraft dropping supplies to the prisoners shortly after the ceasefire in August 1945 spotted the message and soon everyone knew that Pappy was coming back. Although he had never received a single decoration while he was in combat, Boyington returned to the U.S. to find that he not only had been awarded the Navy Cross, but the Medal of Honor as well, albeit "posthumously." With Pappy Boyington gone, several other young Marine aviators began to make themselves known. The most productive, and unfortunately, the one with the shortest career, was First Lieutenant Robert M. Hanson of VMF-215. Although born in India of missionary parents, Hanson called Massachusetts home. A husky, competitive man, he quickly took to the life of a Marine combat aviator. During his first and second tours, flying from Vella Lavella with other squadrons, including Boyington's Black Sheep, Hanson shot down five Japanese planes, although during one of these fights, he, himself, was forced to ditch his Corsair in Empress Augusta Bay.

For his third tour, he joined VMF 215 at Torokina. By mid-January, Hanson had begun such a hot streak of kills, that the young pilot had earned the name "Butcher Bob." Hanson shot Japanese planes down in bunches. On 18 January 1944, he disposed of five enemy aircraft. On 24 January, he added four more Zeros. Another four Japanese planes went down before Hanson's Corsair on 30 January. His score now stood at 25, 20 of which had been gained in 13 days in only six missions. Hanson's successes were happening so quickly that he was relatively un known outside his combat area. Very few combat correspondents knew of his record until later. Lieutenant Hanson took off for a mission on 3 February 1944. The next day would be his 24th birthday, and the squadron's third tour would end in a few days. He was going back home. He called his flight commander, Captain Harold L. Spears, and asked if he could strafe Japanese antiaircraft artillery positions at Cape St. George on New Ireland, the same general area over which Pappy Boyington had been shot down a month before. Hanson made his run, firing his plane's six .50-caliber machine guns. The Japanese returned fire as the big, blue-gray Marine fighter rocketed past, seemingly under control. However, Hanson's plane dove into the water from a low altitude, leaving only an oil slick. Hanson's meteoric career saw him become the highest-scoring Marine Corsair ace, and the second Marine high-scorer, one behind Joe Foss. Lieutenant Hanson received a posthumous Medal of Honor for his third tour of combat. As Barrett Tillman points out in his book on the F4U, Hanson "became the third and last Corsair pilot to receive the Medal of Honor in World War II. And the youngest."

|