| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. The Landing and August Battles (continued)

Even though most of the division's heavy engineering equipment had disappeared with the Navy's transports, the resourceful Marines soon completed the airfield's runway with captured Japanese gear. On 12 August Admiral McCain's aide piloted a PBY-5 Catalina flying boat and bumped to a halt on what was now officially Henderson Field, named for a Marine pilot, Major Lofton R. Henderson, lost at Midway. The Navy officer pronounced the airfield fit for fighter use and took off with a load of wounded Marines, the first of 2,879 to be evacuated. Henderson Field was the centerpiece of Vandegrift's strategy; he would hold it at all costs. Although it was only 2,000 feet long and lacked a taxiway and adequate drainage, the tiny airstrip, often riddled with potholes and rendered unusable because of frequent, torrential downpours, was essential to the success of the landing force. With it operational, supplies could be flown in and wounded flown out. At least in the Marines' minds, Navy ships ceased to be the only lifeline for the defenders. While Vandegrift's Marines dug in east and west of Henderson Field, Japanese headquarters in Rabaul planned what it considered an effective response to he American offensive. Misled by intelligence estimates that the Marines numbered perhaps 2,000 men, Japanese staff officers believed that a modest force quickly sent could overwhelm the invaders. On 12 August, CinCPac determined that a sizable Japanese force was massing at Truk to steam to the Solomons and attempt to eject the Americans. Ominously, the group included the heavy carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku and the light carrier Ryujo. Despite the painful losses at Savo Island, the only significant increases to American naval forces in the Solomons was the assignment of a new battleship, the South Dakota (BB-57).

Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo had ordered Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake's Seventeenth Army to attack the Marine perimeter. For his assault force, Hyakutake chose the 35th Infantry Brigade (Reinforced), commanded by Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi. At the time, Kawaguchi's main force was in the Palaus. Hyakutake selected a crack infantry regiment—the 28th—commanded by Colonel Kiyono Ichiki to land first. Alerted for its mission while it was at Guam, the Ichiki Detachment assault echelon, one battalion of 900 men, was transported to the Solomons on the only shipping available, six destroyers. As a result the troops carried just small amounts of ordnance and supplies. A follow-on echelon of 1,200 of Ichiki's troops was to join the assault battalion on Guadalcanal.

While the Japanese landing force was headed for Guadalcanal, the Japanese already on the island provided an unpleasant reminder that they, too, were full of fight. A captured enemy naval rating, taken in the constant patrolling to the west of the perimeter, indicated that a Japanese group wanted to surrender near the village of Kokumbona, seven miles west of the Matanikau. This was the area that Lieutenant Colonel Goettge considered held most of the enemy troops who had fled the airfield. On the night of 12 August, a reconnaissance patrol of 25 men led by Goettge himself left the perimeter by landing craft. The patrol landed near its objective, was ambushed, and virtually wiped out. Only three men managed to swim and wade back to the Marine lines. The bodies of the other members of the patrol were never found. To this day, the fate of the Goettge patrol continues to intrigue researchers.

After the loss of Goettge and his men, vigilance increased on the perimeter. On the 14th, a fabled character, the coastwatcher Martin Clemens, came strolling out of the jungle into the Marine lines. He had watched the landing from the hills south of the airfield and now brought his bodyguard of native policemen with him. A retired sergeant major of the British Solomon Islands Constabulary, Jacob C. Vouza, volunteered about this time to search out Japanese to the east of the perimeter, where patrol sightings and contacts had indicated the Japanese might have effected a landing. The ominous news of Japanese sightings to he east and west of the perimeter were balanced out by the joyous word that more Marines had landed. This time the Marines were aviators. On 20 August, two squadrons of Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 23 were launched from the escort carrier Long Island (CVE-1) located 200 miles southeast of Guadalcanal. Captain John L. Smith led 19 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 223 onto Henderson's narrow runway. Smith's fighters were followed by Major Richard C. Mangrum's Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron (VMSB) 232 with 12 Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers. From this point of the campaign, the radio identification for Guadalcanal, Cactus, became increasingly synonymous with the island. The Marine planes became the first elements of what would informally be known as Cactus Air Force. Wasting no time, the Marine pilots were soon in action against the Japanese naval aircraft which frequently attacked Guadalcanal. Smith shot down his first enemy Zero fighter on 21 August; three days later VMF-223's Wildcats intercepted a strong Japanese aerial attack force and downed 16 enemy planes. In this action, Captain Marion E. Carl, a veteran of Midway, shot down three planes. On the 22d, coastwatchers alerted Cactus to an approaching air attack and 13 of 16 enemy bombers were destroyed. At the same time, Mangrum's dive bombers damaged three enemy destroyer-transports attempting to reach Guadalcanal. On 24 August, the American attacking aircraft, which now included Navy scout-bombers from the Saratoga's Scouting Squadron (VS) 5, succeeded in turning back a Japanese reinforcement convoy of warships and destroyers.

On 22 August, five Bell P-400 Air Cobras of the Army's 67th Fighter Squadron had landed at Henderson, followed within a week by nine more Air Cobras. The Army planes, which had serious altitude and climb-rate deficiencies, were destined to see most action in ground combat support roles.

The frenzied action in what became known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons was matched ashore. Japanese destroyers had delivered the vanguard of the Ichiki force at Taivu Point, 25 miles east of the Marine perimeter. A long-range patrol of Marines from Company A, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines ambushed a sizable Japanese force near Taivu on 19 August. The Japanese dead were readily identified as Army troops and the debris of their defeat included fresh uniforms and a large amount of communication gear. Clearly , a new phase of the fighting had begun. All Japanese encountered to this point had been naval troops. Alerted by patrols, the Marines now dug in along the Ilu River, often misnamed the Tenaru on Marine maps, were ready for Colonel Ichiki. The Japanese commander's orders directed him to "quickly recapture and maintain the airfield at Guadalcanal," and his own directive to his troops emphasized that they would fight "to the last breath of the last man." And they did. Too full of his mission to wait for the rest of his regiment and sure that he faced only a few thousand men overall, Ichiki marched from Taivu to the Marines' lines. Before he attacked on the night of the 20th, a bloody figure stumbled out of the jungle with a warning that the Japanese were coming. It was Sergeant Major Vouza. Captured by the Japanese, who found a small American flag secreted in his loincloth, he was tortured in a failed attempt to gain information on the invasion force. Tied to a tree, bayonetted twice through the chest, and beaten with rifle butts, the resolute Vouza chewed through his bindings to escape. Taken to Lieutenant Colonel Edwin A. Pollock, whose 2d Battalion, 1st Marines held the Ilu mouth's defenses, he gasped a warning that an estimated 250-500 Japanese soldiers were coming behind him. The resolute Vouza, rushed immediately to an aid station and then to the division hospital, miraculously survived his ordeal and was awarded a Silver Star for his heroism by General Vandegrift, and later a Legion of Merit. Vandegrift also made Vouza an honorary sergeant major of U.S. Marines.

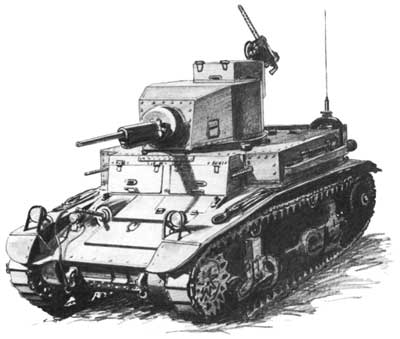

At 0130 on 21 August, Ichiki's troops stormed the Marines' lines in a screaming, frenzied display of the "spiritual strength" which they had been assured would sweep aside their American enemy. As the Japanese charged across the sand bar astride the Ilu's mouth, Pollock's Marines cut them down. After a mortar preparation, the Japanese tried again to storm past the sand bar. A section of 37mm guns sprayed the enemy force with deadly canister. Lieutenant Colonel Lenard B. Cresswell's 1st Battalion, 1st Marines moved upstream on the Ilu at daybreak, waded across the sluggish, 50-foot-wide stream, and moved on the flank of the Japanese. Wildcats from VMF-223 strafed the beleaguered enemy force. Five light tanks blasted the retreating Japanese. By 1700, as the sun was setting, the battle ended. Colonel Ichiki[*], disgraced in his own mind by his defeat, burned his regimental colors and shot himself. Close to 800 of his men joined him in death. The few survivors fled eastward towards Taivu Point. Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, whose reinforcement force of transports and destroyers was largely responsible for the subsequent Japanese troop build-up on Guadalcanal, recognized that the unsupported Japanese attack was sheer folly and reflected that "this tragedy should have taught us the hopelessness of bamboo spear tactics." Fortunately for the Marines, Ichiki's overconfidence was not unique among Japanese commanders.

Following the 1st Marines' tangle with the Ichiki detachment, General Vandegrift was inspired to write the Marine Commandant, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, and report: "These youngsters are the darndest people when they get started you ever saw." And all the Marines on the island, young and old, tyro and veteran, were becoming accomplished jungle fighters. They were no longer "trigger happy" as many had been in their first days shore, shooting at shadows and imagined enemy. They were waiting for targets, patrolling with enthusiasm, sure of themselves. The misnamed Battle of the Tenaru had cost Colonel Hunt's regiment 34 killed in action and 75 wounded. All the division's Marines now felt they were bloodied. What the men on Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo and those of the Ilu had done was prove that the 1st Marine Division would hold fast to what it had won.

While the division's Marines and sailors had earned a breathing spell as the Japanese regrouped for another onslaught, the action in the air over the Solomons intensified. Almost every day, Japanese aircraft arrived around noon to bomb the perimeter. Marine fighter pilots found the twin-engine Betty bombers easy targets; Zero fighters were another story. Although the Wildcats were a much sturdier aircraft, the Japanese Zeros' superior speed and better maneuverability gave them a distinct edge in a dogfight. The American planes, however, when warned by the coastwatchers of Japanese attacks, had time to climb above the oncoming enemy and preferably attacked by making firing runs during high speed dives. Their tactics made the air space over the Solomons dangerous for the Japanese. On 29 August, the carrier Ryujo launched aircraft for a strike against the airstrip. Smith's Wildcats shot down 16, with a loss of four of their own. Still, the Japanese continued to strike at Henderson Field without letup. Two days after the Ryujo raid, enemy bombers inflicted heavy damage on the airfield, setting aviation fuel ablaze and incinerating parked aircraft. VMF-223's retaliation was a further bag of 13 attackers. On 30 August, two more MAG-23 squadrons, VMF-224 and VMSB-231, flew in to Henderson. The air reinforcements were more than welcome. Steady combat attrition, frequent damage in the air and on the ground, and scant repair facilities and parts kept the number of aircraft available a dwindling resource. Plainly, General Vandegrift needed infantry reinforcements as much as he did additional aircraft. He brought the now-combined raider and parachute battalions, both under Edson's command, and the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, over to Guadalcanal from Tulagi. This gave the division commander a chance to order out larger reconnaissance patrols to probe for the Japanese. On 27 August, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, made a shore-to-shore landing near Kokumbona and marched back to the beachhead without any measurable results. If the Japanese were out there beyond the Matanikau—and they were—they watched the Marines and waited for a better opportunity to attack.

|