| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

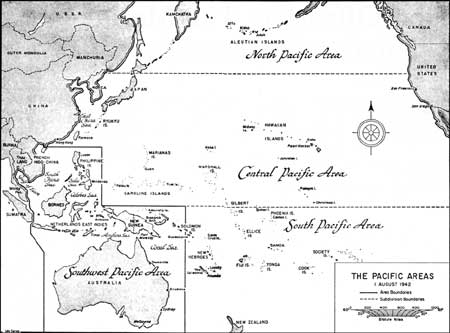

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. In the early summer of 1942, intelligence reports of the construction of a Japanese airfield near Lunga Point on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands triggered a demand for offensive action in the South Pacific. The leading offensive advocate in Washington was Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). In the Pacific, his view was shared by Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (CinCPac), who had already proposed sending the 1st Marine Raider Battalion to Tulagi, an island 20 miles north of Guadalcanal across Sealark Channel, to destroy a Japanese seaplane base there. Although the Battle of the Coral Sea had forestalled a Japanese amphibious assault on Port Moresby, the Allied base of supply in eastern New Guinea, completion of the Guadalcanal airfield might signal the beginning of a renewed enemy advance to the south and an increased threat to the lifeline of American aid to New Zealand and Australia. On 23 July 1942. the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in Washington agreed that the line of communications in the South Pacific had to be secured. The Japanese advance had to be stopped. Thus, Operation Watchtower, the seizure of Guadalcanal and Tulagi, came into being. The islands of the Solomons lie nestled in the backwaters of the South Pacific. Spanish fortune-hunters discovered them in the mid-sixteenth century, but no European power foresaw any value in the islands until Germany sought to expand its budding colonial empire more than two centuries later. In 1884, Germany proclaimed a protectorate over northern New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the northern Solomons. Great Britain countered by establishing a protectorate over the southern Solomons and by annexing the remainder of New Guinea. In 1905, the British crown passed administrative control over all its territories in the region to Australia, and the Territory of Papua, with its capital at Port Moresby, came into being. Germany's holdings in the region fell under the administrative control of the League of Nations following World War I, with the seat of the colonial government located at Rabaul on New Britain. The Solomons lay 10 degrees below the Equator—hot, humid, and buffeted by torrential rains. The celebrated adventure novelist, Jack London, supposedly muttered: "If I were king, the worst punishment I could inflict on my enemies would be to banish them to the Solomons."

On 23 January 1942, Japanese forces seized Rabaul and fortified it extensively. The site provided excellent harbor and numerous positions for airfields. The devastating enemy carrier and plane losses of the Battle of Midway (3-6 June 1942) had caused Imperial General Headquarters to cancel orders for the invasion of Midway, New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa, but plans to construct a major seaplane base at Tulagi went forward. The location offered on of the best anchorages in the South Pacific and it was strategically located: 560 miles from the New Hebrides, 800 miles from New Caledonia, and 1,000 miles from Fiji The outposts at Tulagi and Guadalcanal were the forward evidences of a sizeable Japanese force in the region, beginning with the Seventeenth Army, headquartered at Rabaul. The enemy's Eighth Fleet, Eleventh Air Fleet, and 1st, 7th, 8th, and 14th Naval Base Forces also were on New Britain. Beginning on 5 August 1942, Japanese signal intelligence units began to pick up transmissions between Noumea on New Caledonia and Melbourne, Australia. Enemy analysts concluded that Vice Admiral Richard L. Ghormley, commanding the South Pacific Area (ComSoPac), was signaling a British or Australian force in preparation for an offensive in the Solomons or at New Guinea. The warnings were passed to Japanese headquarters at Rabaul and Truk, but were ignored. The invasion force was indeed on its way to its targets, Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the tiny islets of Gavutu and Tanambogo close by Tulagi's shore. The landing force was composed of Marines; the covering force and transport force were U.S. Navy with a reinforcement of Australian warships. There was not much mystery to the selection of the 1st Marine Division to make the landings. Five U.S. Army divisions were located in the South and Southwest Pacific: three in Australia, the 37th Infantry in Fiji, and the Americal Division on New Caledonia. None was amphibiously trained and all were considered vital parts of defensive garrisons. The 1st Marine Division, minus one of its infantry regiments, had begun arriving in New Zealand in mid-June when the division headquarters and the 5th Marines reached Wellington. At that time, the rest of the reinforced division's major units were getting ready to embark. The 1st Marines were at San Francisco, the 1st Raider Battalion was on New Caledonia, and the 3d Defense Battalion was at Pearl Harbor. The 2d Marines of the 2d Marine Division, a unit which would replace the 1st Division's 7th Marines stationed in British Samoa, was loading out from San Diego. All three infantry regiments of the landing force had battalions of artillery attached, from the 11th Marines, in the case of the 5th and 1st; the 2d Marines drew its reinforcing 75mm howitzers from the 2d Division's 10th Marines.

The news that his division would be the landing force for Watchtower came as a surprise to Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, who had anticipated that the 1st Division would have six months of training in the South Pacific before it saw action. The changeover from administrative loading of the various units' supplies to combat loading, where first-needed equipment, weapons, ammunition, and rations were positioned to come off ships first with the assault troops, occasioned a never-to-be-forgotten scene on Wellington's docks. The combat troops took the place of civilian stevedores and unloaded and reloaded the cargo and passenger vessels in an increasing round of working parties, often during rainstorms which hampered the task, but the job was done. Succeeding echelons of the division's forces all got their share of labor on the docks as various shipping groups arrived and the time grew shorter. General Vandegrift was able to convince Admiral Ghormley and the Joint Chiefs that he would not be able to meet a proposed D-Day of 1 August, but the extended landing date, 7 August, did little to improve the situation. An amphibious operation is a vastly complicated affair, particularly when the forces involved are assembled on short notice from all over the Pacific. The pressure that Vandegrift felt was not unique to the landing force commander. The U.S. Navy's ships were the key to success and they were scare and invaluable. Although the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway had badly damaged the Japanese fleet's offensive capabilities and crippled its carrier forces, enemy naval aircraft could fight as well ashore as afloat and enemy warships were still numerous and lethal. American losses at Pearl Harbor, Coral Sea, and Midway were considerable, and Navy admirals were well aware that the ships they commanded were in short supply. The day was coming when America's shipyards and factories would fill the seas with warships of all types, but that day had not arrived in 1942. Calculated risk was the name of the game where the Navy was concerned, and if the risk seemed too great, the Watchtower landing force might be a casualty. As it happened, the Navy never ceased to risk its ships in the waters of the Solomons, but the naval lifeline to the troops ashore stretched mighty thin at times.

Tactical command of the invasion force approaching Guadalcanal in early August was vested in Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher as Expeditionary Force Commander (Task Force 61). His force consisted of the amphibious shipping carrying the 1st Marine Division, under Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, and the Air Support Force led by Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes. Admiral Ghormley contributed land-based air forces commanded by Rear Admiral John S. McCain. Fletcher's support force consisted of three fleet carriers, the Saratoga (CV-3), Enterprise (CV-6), and Wasp (CV-7); the battleship North Carolina (BB-55), 6 cruisers, 16 destroyers, and 3 oilers. Admiral Turner's covering force included five cruisers and nine destroyers.

|