| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

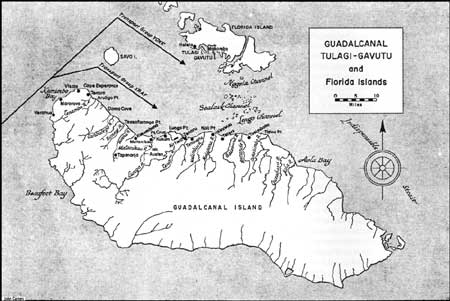

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. The Landing and August Battles On board the transports approaching the Solomons, the Marines were looking for a tough fight. They knew little about the targets, even less about their opponents. Those maps that were available were poor, constructions based upon outdated hydrographic charts and information provided by former island residents. While maps based on aerial photographs had been prepared they were misplaced by the Navy in Auckland, New Zealand, and never got to the Marines at Wellington. On 17 July, a couple of division staff officers, Lieutenant Colonel Merrill B. Twining and Major William McKean, had been able to join the crew of a B-17 flying from Port Moresby on a reconnaissance mission over Guadalcanal. They reported what they had seen, and their analysis, coupled with aerial photographs, indicated no extensive defenses along the beaches of Guadalcanal's north shore.

This news was indeed welcome. The division intelligence officer (G-2), Lieutenant Colonel Frank B. Goettge, had concluded that about 8,400 Japanese occupied Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Admiral Turner's staff figured that the Japanese amounted to 7,125 men. Admiral Ghormley's intelligence officer pegged the enemy strength at 3,100—closest to the 3,457 actual total of Japanese troops; 2,571 of these were stationed on Guadalcanal and were mostly laborers working on the airfield.

To oppose the Japanese, the Marines had an overwhelming superiority of men. At the time, the tables of organization for a Marine Corps division indicated a total of 19,514 officers and enlisted men, including naval medical and engineer (Seabee) units. Infantry regiments numbered 3,168 and consisted of a headquarters company, a weapons company, and three battalions. Each infantry battalion (933 Marines) was organized into a headquarters company (89), a weapons company (273), and three rifle companies (183). The artillery regiment had 2,581 officers and men organized into three 75mm pack howitzer battalions and one 105mm howitzer battalion. A light tank battalion, a special weapons battalion of antiaircraft and antitank guns, and a parachute battalion added combat power. An engineer regiment (2,452 Marines) with battalions of engineers, pioneers, and Seabees, provided a hefty combat and service element. The total was rounded out by division headquarters battalion's headquarters, signal, and military police companies and the division's service troops—service, motor transport, amphibian tractor, and medical battalions. For Watchtower, the 1st Raider Battalion and the 3d Defense Battalion had been added to Vandegrift's command to provide more infantrymen and much needed coast defense and antiaircraft guns and crews. Unfortunately, the division's heaviest ordnance had been left behind in New Zealand. Limited ships' space and time meant that the division's big guns, a 155mm howitzer battalion, and all the motor transport battalion's two-and-a-half-ton trucks were not loaded. Colonel Pedro A. del Valle, commanding the 11th Marines, was unhappy at the loss of his heavy howitzers and equally distressed that essential sound and flash-ranging equipment necessary for effective counterbattery fire was left behind. Also failing to make the cut in the battle for shipping space, were all spare clothing, bedding rolls, and supplies necessary to support the reinforced division beyond 60 days of combat. Ten days supply of ammunition for each of the division's weapons remained in New Zealand.

In the opinion of the 1st Division's historian and a veteran of the landing, the men on the approaching transports "thought they'd have a bad time getting ashore." They were confident, certainly, and sure that they could not be defeated, but most of the men were entering combat for the first time. There were combat veteran officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs) throughout the division, but the majority of the men were going into their initial battle. The commanding officer of the 1st Marines, Colonel Clifton B. Cates, estimated that 90 percent of his men had enlisted after Pearl Harbor. The fabled 1st Marine Division of later World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, and Persian Gulf War fame, the most highly decorated division in the U.S. Armed Forces, had not yet established its reputation. The convoy of ships, with its outriding protective screen of carriers, reached Koro in the Fiji Islands on 26 July. Practice landings did little more than exercise the transports' landing craft, since reefs precluded an actual beach landing. The rendezvous at Koro did give the senior commanders a chance to have a face-to-face meeting. Fletcher, McCain, Turner, and Vandegrift got together with Ghormley's chief of staff, Rear Admiral Callaghan, who notified the conferees that ComSoPac had ordered the 7th Marines on Samoa to be prepared to embark on four days notice as a reinforcement for Watchtower. To this decidedly good news, Admiral Fletcher added some bad news. In view of the threat from enemy land-based air, he could not "keep the carriers in the area for more than 48 hours after the landing." Vandegrift protested that he needed at least four days to get the division's gear ashore, and Fletcher reluctantly agreed to keep his carriers at risk another day. On the 28th the ships sailed from the Fijis, proceeding as if they were headed for Australia. At noon on 5 August, the convoy and its escorts turned north for the Solomons. Undetected by the Japanese, the assault force reached its target during the night of 6-7 August and split into two landing groups, Transport Division X-Ray, 15 transports heading for the north shore of Guadalcanal east of Lunga Point, and Transport Division Yoke, eight transports headed for Tulagi, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and the nearby Florida Island, which loomed over the smaller islands. Vandegrift's plans for the landings would put two of his infantry regiments (Colonel LeRoy P. Hunt's 5th Marines and Colonel Cates' 1st Marines) ashore on both sides of the Lunga River prepared to attack inland to seize the airfield. The 11th Marines, the 3d Defense Battalion, and most of the division's supporting units would also land near the Lung, prepared to exploit the beachhead. Across the 20 miles of Sealark Channel, the division's assistant commander, Brigadier General William H. Rupertus, led the assault forces slated to take Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo: the 1st Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson); the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Harold E. Rosecrans); and the 1st Parachute Battalion (Major Robert H. Williams). Company A of the 2d Marines would reconnoiter the nearby shores of Florida Island and the rest of Colonel John A. Arthur's regiment would stand by in reserve to land where needed. As the ships slipped through the channels on either side of rugged Savo Island, which split Sealark near its western end, heavy clouds and dense rain blanketed the task force. Later the moon came out and silhouetted the islands. On board his command ship, Vandegrift wrote to his wife: "Tomorrow morning at dawn we land in our first major offensive of the war. Our plans have been made and God grant that our judgement has been sound ... whatever happens you'll know I did my best. Let us hope that best will be good enough." At 0641 on 7 August, Turner signalled his ships to "land the landing force." Just 28 minutes before, the heavy cruiser Quincy (CA-39) had begun shelling the landing beaches at Guadalcanal. The sun came up that fateful Friday at 0650, and the first landing craft carrying assault troops of the 5th Marines touched down at 0909 on Red Beach. To the men's surprise (and relief), no Japanese appeared to resist the landing. Hunt immediately moved his assault troops off the beach and into the surrounding jungle, waded the steep-banked Ilu River, and headed for the enemy airfield. The following 1st Marines were able to cross the Ilu on a bridge the engineers had hastily thrown up with an amphibian tractor bracing its middle. The silence was eerie and the absence of opposition was worrisome to me riflemen. The Japanese troops, most of whom were Korean laborers, had fled to the west, spooked by a week's B-17 bombardment, the pre-assault naval gunfire, and the sight of the ships offshore. The situation was not the same across Sealark. The Marines on Guadalcanal could hear faint rumbles of a firefight across the waters.

The Japanese on Tulagi were special naval landing force sailors and they had no intention of giving up what they held without a vicious, no-surrender battle. Edson's men landed first, followed by Rosecrans' battalion, hitting Tulagi's south coast and moving inland towards the ridge which ran lengthwise through the island. The battalions encountered pockets of resistance in the undergrowth of the island's thick vegetation and maneuvered to outflank and overrun the opposition. The advance of the Marines was steady but casualties were frequent. By nightfall, Edson had reached the former British residency overlooking Tulagi's harbor and dug in for the night across a hill that overlooked the Japanese final position, a ravine on the island's southern tip. The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, had driven through to the northern shore, cleaning its sector of enemy; Rosecrans moved into position to back up the raiders. By the end of its first day ashore, 2d Battalion had lost 56 men killed and wounded; 1st Raider Battalion casualties were 99 Marines.

|