| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FIRST OFFENSIVE: The Marine Campaign for Guadalcanal by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. The Landing and August Battles (continued) Throughout the night, the Japanese swarmed from hillside caves in four separate attacks, trying to penetrate the raider lines. They were unsuccessful and most died in the attempts. At dawn, the 2d Battalion, 2d Marines, landed to reinforce the attackers and by the afternoon of 8 August, the mop-up was completed and the battle for Tulagi was over. The fight for tiny Gavutu and Tanambogo, both little more than small hills rising out of the sea, connected by a hundred-yard causeway, was every bit as intense as that on Tulagi. The area of combat was much smaller and the opportunities for fire support from offshore ships and carrier planes was severely limited once the Marines had landed. After naval gunfire from the light cruiser San Juan (CL-54) and two destroyers, and a strike by F4F Wildcats flying from the Wasp, the 1st Parachute Battalion landed near noon in three waves, 395 men in all, on Gavutu. The Japanese, secure in cave positions, opened fire on the second and third waves, pinning down the first Marines ashore on the beach. Major Williams took a bullet in the lungs and was evacuated; 32 Marines were killed in the withering enemy fire. This time, 2d Marines reinforcements were really needed; the 1st Battalion's Company B landed on Gavutu and attempted to take Tanambogo; the attackers were driven to ground and had to pull back to Gavutu. After a rough night of close-in fighting with the defenders of both islands, the 3d Battalion, 2d Marines, reinforced the men already ashore and mopped up on each island. The toll of Marines dead on the three islands was 144; the wounded numbered 194. The few Japanese who survived the battles fled to Florida Island, which had been scouted by the 2d Marines on D-Day and found clear of the enemy. The Marines' landings and the concentration of shipping in Guadalcanal waters acted as a magnet to the Japanese at Rabaul. At Admiral Ghormley's headquarters, Tulagi's radio was heard on D-Day "frantically calling for [the] dispatch of surface forces to the scene" and designating transports and carriers as targets for heavy bombing. The messages were sent in plain language, emphasizing the plight of the threatened garrison. And the enemy response was prompt and characteristic of the months of naval air and surface attack to come.

At 1030 on 7 August, an Australian coastwatcher hidden in the hills of the islands north of Guadalcanal signalled that a Japanese air strike composed of heavy bombers, light bombers, and fighters was headed for the island. Fletcher's pilots, whose carriers were positioned 100 miles south of Guadalcanal, jumped the approaching planes 20 miles northwest of the landing areas before they could disrupt the operation. But the Japanese were not daunted by the setback; other planes and ships were enroute to the inviting target. On 8 August, the Marines consolidated their positions ashore, seizing the airfield on Guadalcanal and establishing a beachhead. Supplies were being unloaded as fast as landing craft could make the turnaround from ship to shore, but the shore party was woefully inadequate to handle the influx of ammunition, rations, tents, aviation gas, vehicles—all gear necessary to sustain the Marines. The beach itself became a dumpsite. And almost as soon as the initial supplies were landed, they had to be moved to positions nearer Kukum village and Lunga Point within the planned perimeter. Fortunately, the lack of Japanese ground opposition enabled Vandegrift to shift the supply beaches west to a new beachhead.

Japanese bombers did penetrate the American fighter screen on 8 August. Dropping their bombs from 20,000 feet or more to escape antiaircraft fire, the enemy planes were not very accurate. They concentrated on the ships in the channel, hitting and damaging a number of them and sinking the destroyer Jarvis (DD-393). In their battles to turn back the attacking planes, the carrier fighter squadrons lost 21 Wildcats on 7-8 August. The primary Japanese targets were the Allied ships. At this time, and for a thankfully and unbelievably long time to come, the Japanese commanders at Rabaul grossly underestimated the strength of Vandegrift's forces. They thought the Marine landings constituted a reconnaissance in force, perhaps 2,000 men, on Guadalcanal. By the evening of 8 August, Vandegrift had 10,900 troops ashore on Guadalcanal and another 6,075 on Tulagi. Three infantry regiments had landed and each had a supporting 75mm pack howitzer battalion—the 2 and 3d Battalions, 11th Marines on Guadalcanal, and the 3d Battalion, 10th Marines on Tulagi. The 5th Battalion, 11th Marines' 105mm howitzers were in general support. That night a cruiser-destroyer force of the Imperial Japanese Navy reacted to the American invasion with a stinging response. Admiral Turner had positioned three cruiser-destroyer groups to bar the Tulagi-Guadalcanal approaches. At the Battle of Savo, the Japanese demonstrated their superiority in night fighting at this stage of the war, shattering two of Turner's covering forces without loss to themselves. Four heavy cruisers went to the bottom—three American, one Australian—and another lost her bow. As the sun came up over what soon would be called "Ironbottom Sound," Marines watched grimly as Higgins boats swarmed out to rescue survivors. Approximately 1,300 sailors died that night and another 700 suffered wounds or were badly burned. Japanese casualties numbered less than 200 men. The Japanese suffered damage to only one ship in the encounter, the cruiser Chokai. The American cruisers Vincennes (CA-44), Astoria (CA-34), and Quincy (CA-39) went to the bottom, as did the Australian Navy's HMAS Canberra, so critically damaged that she had to be sunk by American torpedoes. Both the cruiser Chicago (CA-29) and destroyer Talbot (DD-114) were badly damaged. Fortunately for the Marines ashore, the Japanese force—five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer—departed before dawn without attempting to disrupt the landing further.

When the attack-force leader, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, returned to Rabaul, he expected to receive the accolades of his superiors. He did get those, but he also found himself the subject of criticism. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese fleet commander, chided his subordinate for failing to attack the transports. Mikawa could only reply, somewhat lamely, that he did not know Fletcher's aircraft carriers were so far away from Guadalcanal. Of equal significance to the Marines on the beach, the Japanese naval victory caused celebrating superiors in Tokyo to allow the event to overshadow the importance of the amphibious operation. The disaster prompted the American admirals to reconsider Navy support for operations ashore. Fletcher feared for the safety of his carriers; he had already lost about a quarter of his fighter aircraft. The commander of the expeditionary force had lost a carrier at Coral Sea and another at Midway. He felt he could not risk the loss of a third, even if it meant leaving the Marines on their own. Before the Japanese cruiser attack, he obtained Admiral Ghormley's permission to withdraw from the area.

At a conference on board Turner's flagship transport, the McCawley, on the night of 8 August, the admiral told General Vandegrift that Fletcher's impending withdrawal meant that he would have to pull out the amphibious force's ships. The Battle of Savo Island reinforced the decision to get away before enemy aircraft, unchecked by American interceptors, struck. On 9 August, the transports withdrew to Noumea. The unloading of supplies ended abruptly, and ships still half-full steamed away. The forces ashore had 17 days' rations—after counting captured Japanese food—and only four days' supply of ammunition for all weapons. Not only did the ships take away the rest of the supplies, they also took the Marines still on board, including the 2d Marines' headquarters element. Dropped off at the island of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, the infantry Marines and their commander, Colonel Arthur, were most unhappy and remained so until they finally reached Guadalcanal on 29 October. Ashore in the Marine beachheads, General Vandegrift ordered rations reduced to two meals a day. The reduced food intake would last for six weeks, and the Marines would become very familiar with Japanese canned fish and rice. Most of the Marines smoked and they were soon disgustedly smoking Japanese-issue brands. They found that the separate paper filters that came with the cigarettes were necessary to keep the fast-burning tobacco from scorching their lips. The retreating ships had also hauled away empty sand bags and valuable engineer tools. So the Marines used Japanese shovels to fill Japanese rice bags with sand to strengthen their defensive positions.

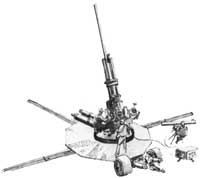

The Marines dug in along the beaches between the Tenaru and the ridges west of Kukum. A Japanese counter-landing was a distinct possibility. Inland of the beaches, defensive gun pits and foxholes lined the west bank of the Tenaru and crowned the hills that faced west toward the Matanikau River and Point Cruz. South of the airfield where densely jungled ridges and ravines abounded, the beachhead perimeter was guarded by outposts and these were manned in large part by combat support troops. The engineer, pioneer, and amphibious tractor battalion all had their positions on the front line. In fact, any Marine with a rifle, and that was virtually every Marine, stood night defensive duty. There was no place within the perimeter that could be counted safe from enemy infiltration. Almost as Turner's transports sailed away, the Japanese began a pattern of harassing air attacks on the beachhead. Sometimes the raids came during the day, but the 3d Defense Battalion's 90mm antiaircraft guns forced the bombers to fly too high for effective bombing. The erratic pattern of bombs, however, meant that no place was safe near the airfield, the preferred target, and no place could claim it was bomb-free. The most disturbing aspect of Japanese air attacks soon became the nightly harassment by Japanese aircraft which singly, it seemed, roamed over the perimeter, dropping bombs and flares indiscriminately. The nightly visitors, whose planes' engines were soon well known sounds, won the singular title "Washington machine Charlie," at first, and later, "Louie the Louse," when their presence heralded Japanese shore bombardment. Technically, "Charlie" was a twin-engine night bomber from Rabaul. "Louie" was a cruiser float plane that signalled the harassed Marines used the names interchangeably.

|