|

The Manhattan Project was an unprecedented, top-secret World War II government program in which the United States rushed to develop and deploy the world’s first atomic weapons before Nazi Germany. The use of these weapons by the United States against Japan in August 1945 ultimately became one of the most important historical events of the 20th century. The project ushered in the nuclear age and left enduring legacies that echo all around us today. The Manhattan Project took shape at three primary locations across the country: Hanford, Washington; Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

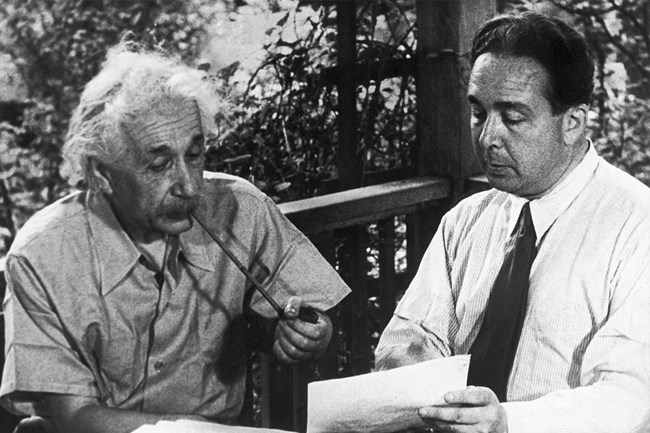

PUBLIC DOMAIN Race to build atomic weaponsScientists in Germany discovered fission in December 1938. Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard realized that nuclear chain reactions could be used to create new and extremely powerful atomic weapons. In August 1939, Szilard wrote a letter for Albert Einstein to sign and send to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning that an "extremely powerful bomb" might be constructed. Fearing ongoing research and development by Nazi Germany, Roosevelt formed the Advisory Committee on Uranium, which met for the first time on October 21, 1939.

ADOBE STOCK Multiple paths forwardScientists theorized there were two potential paths to building an atomic bomb. One path would use the uranium 235 isotope, which comprises on average less than one percent of naturally occurring uranium. The other would use the newly discovered element plutonium, which could be produced in a nuclear reactor using uranium fuel. Both paths required the use of expensive and unproven processes, and success was by no means guaranteed. As a result, the decision was made to move forward with both paths and establish three main sites to support the project. The project would also involve numerous smaller sites around the nation and the world.Three centers of operationThe US Army Corps of Engineers began a nation-wide search for three rural sites that each met a distinct list of criteria. The federal government then used eminent domain authorities in the Second War Power Act of 1942 to acquire the sites, which displaced Tribes, farming communities, and homesteaders. Some only had 30 days to leave and were minimally compensated for their homes. Native Americans were also displaced and lost access to their traditional homelands and subsistence areas. The three sites were:

NPS Oak Ridge, TennesseeA massive industrial complex was built at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to enrich uranium and eventually serve as the headquarters of the nationwide project. Three separate uranium enrichment technologies were pursued in parallel. A pilot reactor and chemical separation plant were also constructed at Oak Ridge to produce a limited amount of plutonium. Hanford, WashingtonOnly six months after breaking ground on the Oak Ridge plutonium pilot plant, an enormous industrial complex for producing plutonium was built at Hanford, Washington. The complex had huge production-scale reactors, chemical separations plants, and fuel fabrication facilities. Despite the speed with which the facilities were engineered and built, production at both the Oak Ridge and Hanford sites was slow and difficult. It was not until mid-1945 that enough enriched uranium and plutonium were available for construction of the first atomic bombs.

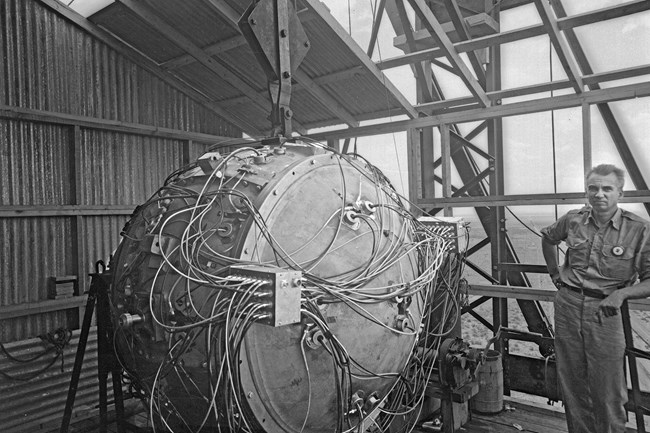

LOS ALAMOS NATIONAL LABORATORY Los Alamos, New MexicoBuilding the bombs themselves was not an easy task. Precise calculations and countless hours of experimentation were required to obtain the optimum specifications of size and shape. In early 1943, General Groves set up a bomb design and development laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, with some of the world's foremost scientists under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer. The laboratory sat atop the Parajito Plateau in an isolated area in northern New Mexico. The uranium bomb utilized a straightforward gun method for creating a critical mass and nuclear explosion. In 1944, scientists determined that a gun-type bomb would not work for plutonium. They turned to the theoretical and extremely complex implosion method. Uncertain that it would work, officials tested the implosion method at the Trinity site in southern New Mexico on July 16, 1945. The Trinity Test ushered in the nuclear age with the world's first human-caused nuclear explosion.

US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY The secret citiesThe Manhattan Project contracted private firms and corporations to build and manage the communities built to house the Manhattan Project workers. Each community became a beehive of activity that boasted of theaters, stores, schools, hospitals, parks, and local gathering places. By 1945, Oak Ridge’s population had soared to about 75,000. Richland, a bedroom community for the Hanford Site, saw its population climb to 15,000 while Los Alamos' population reached 6,000.

ADOBE STOCK (MODIFIED) The bombs are droppedIn just a few short years, the Manhattan Project succeeded in its mission to create the world’s first atomic weapons. During this time, nuclear science advanced at an exponential rate. New discoveries were made in rapid succession. The Manhattan Project produced hundreds of patents both for inhouse scientists and engineers and the numerous contractors involved. Yet, as the project moved closer to the use of the first atomic bomb, ethical questions arose in the minds of some who understood the project’s intent. Scientists and politicians, however, were primarily concerned with ending the war as quickly as possible. On May 8, 1945, Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies ending World War II in Europe. With Germany out of the war, the Allies turned their full attention to the war in the Pacific. The United States dropped the uranium-fueled Little Boy atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. The US then dropped the plutonium-fueled Fat Man bomb on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9. On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan shocking Japanese policy makers. These two countries had signed the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact on April 13, 1941. The atomic bombings and the Soviet Union’s war declaration pushed Emperor Hirohito to announce Japan’s surrender on August 14, 1945. The Japanese formally signed the Instrument of Surrender on September 2, 1945, officially ending the most deadly and destructive war in human history.

SHUTTERSTOCK LegaciesThe Manhattan Project was a highly significant chapter in America’s history that ushered in the nuclear age, determined how the next war, the Cold War, would be fought, and served as the organizational model behind the remarkable achievements of American "big science" during the second half of the twentieth century. The project helped develop three communities—Hanford (the Tri-Cities), Los Alamos, and Oak Ridge—that are thriving today and are now part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. The Manhattan Project also raised ethical and moral questions among scientists and citizens alike—questions that continue to this day. More than 200,000 people died by the end of 1945 as a direct result of the atomic bombings. The advance of nuclear science has given rise to nuclear energy and medicine as well as radioactive waste and health problems. The Manhattan Project and its legacies are complex as the science that made the project possible. Learn about the Manhattan Project |

Last updated: April 17, 2025