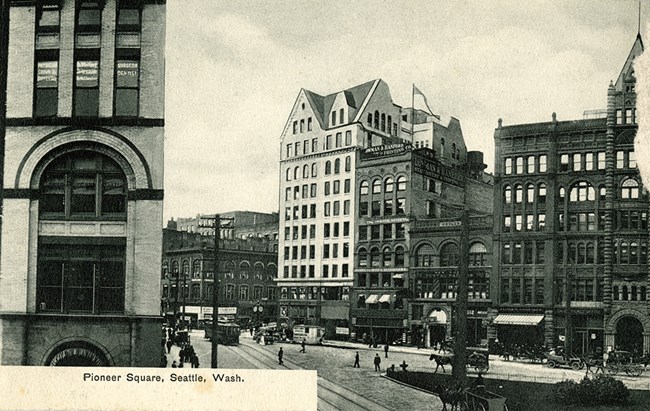

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 57592b. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. A Short History of SeattleSeattle is located on the traditional lands of the Coast Salish Tribes. The Duwamish, Tulalip, Puyallup, Muckleshoot, Suquamish, and Snoqualmie Tribes, who have inhabited the area for time immemorial, are still here. These cultures offer stories of values and resilience rooted in the ancestral lands upon which the park is built. The park's location at Sdzidzilalitch, or Little Crossing Over Place, provides an important touchstone and window into Coast Salish culture. According to local historians, “Coast Salish communities often located villages where they had direct access to resources they could use or trade. Little Crossing-Over Place was adjacent to a flounder fishery, shellfish beds, salmon fishing grounds, places to gather plant resources, and a source of freshwater. It was also a centrally located place where people could gather to socialize, make alliances, trade, and share traditional knowledge.” Read more about Little Crossing Over Place here. This place remains important to the tribes today. The story of Seattle is the story of the Coast Salish, who continue to show resilience through advocating for their homeland and lifeways despite generations of dehumanization and persecution. The first non-Native American settlers arrived a comparatively short time ago. In 1851 they settled briefly at Alki Point, in today's West Seattle, before moving to a more sheltered area a few miles away on the eastern coast of the Sound—now the Pioneer Square Historic District in downtown Seattle. They named their village “Seattle” after Se’alth (Si?al in Lushootseed language), a chief of two local Native American tribes – the Duwamish and Suquamish. Among the original settlers were Arthur Denny and David S. "Doc" Maynard, soon joined by Henry Yesler who sought a site for a steam engine-powered sawmill, which turned the nascent city into an important lumber producer. Aided by animals, wood cutters slid, or "skidded" timber down a greased log road to the sawmill. In time, this "skid road" separated Seattle's affluent and wealthier neighborhoods. "Skid road" evolved into "skid row," a term that refers to the seedy part of a city. In 1860, the first federal census of Washington Territory counted 302 people in King County, most of them in Seattle. Cultural and social advances accompanied population growth. In 1861 the "Washington Territorial University"—today's University of Washington—opened, although 15 years would pass before it granted Clara McCarty its first baccalaureate degree. The city's first newspaper, the Gazette, creaked off an old press in 1863. By 1870 Seattle's population had topped 1,100, and in 1880, 3,500. The Great Seattle FireA devastating fire in 1889 destroyed the city's commercial district. Rebuilding started immediately, the burned wooden structures replaced with more fire-resistant brick and stone buildings. Many of the buildings from this time are still in use. The former Cadillac Hotel, built during this time, is now home to the Seattle unit of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. For more history on these buildings and the Pioneer Square Historic District, visit our Trail to Treasure walking tour page. The fire also provided an opportunity for extensive municipal improvements, including street regrading, a professional fire department, and reconstructed wharves. By 1890 Seattle's population had reached 42,000, an astonishing 12-fold increase since 1880. Contributing to this growth was railroad building, the construction frenzy set off by the 1889 fire, demand for lumber, development of the port, and increased shipping activity. Even greater growth lay ahead. Natural and human-influenced events permanently transformed and continue to impact the landscape and communities. A Fever is IgnitedOn July 17, 1897, the steamship Portland docked in Seattle from St. Michael, Alaska, carrying 68 prospectors and what newspapers said was "a ton of gold." Two days earlier a similarly laden ship had arrived in San Francisco from Alaska. Newspapers spread word that a great quantity of gold had been found along a remote river in what is today the Yukon Territory of Canada. What had been just a few hundred prospectors sailing from Seattle each week, soon turned into a stampede of thousands. The Klondike Gold Rush had begun. Seattle merchants quickly exploited their port status. Advertisements far and wide declared Seattle as the "Gateway to the Gold Fields" - the place where all one's Klondike needs, from food and warm clothing to tents and transportation - could easily be fulfilled. As a result, of the 100,000 people who headed north to the goldfields, 70,000 of them came through Seattle to buy their "ton of goods.” The city prospered from the torrent of people and money funneling through Seattle, dramatically transforming the city during a short span of time.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 57591a. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. Boom and BustIn 1900, Seattle's population had nearly doubled from 1890, to 80,000. Despite occasional downturns, economic and population growth continued in the 20th century. In 1916 William Boeing launched the company bearing his surname that would later become the world's largest aircraft manufacturer. The 1920s brought depressed conditions for all industries, especially the shipbuilding and the lumber trades. The Depression hit Seattle hard, resulting in many unemployed people establishing a "Hooverville" of shacks and lean-tos at an abandoned shipbuilding yard south of Pioneer Square. World War II sparked an economic rebound as shipyards flourished again. While the war helped some populations rebound, others suffered. After the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces on December 7, 1941, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order gave authority to the War Department to create zones from which Japanese Americans could be excluded. The first exclusion area designated was Bainbridge Island. On March 30, 1942, the Japanese Americans living on Bainbridge Island were gathered at the Eagledale Ferry Dock and sent to the concentration camp in Manzanar, California before being transferred to Minidoka. Once World War II ended, about half of the Bainbridge Island Japanese Americans returned to the island to resume their lives, raise families, and pick up where they left off. But burning in their collective conscience was the Japanese phrase Nidoto Nai Yoni, which translates to “Let It Not Happen Again,” and they vowed to honor and recognize the members of their community who spent part of their lives in American concentration camps because of their ancestry, an ethos commemorated by the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial. Seattle’s past and present are laced with laws and covenants of exclusion that have shaped the long-term demographics of the city and impacted communities for generations. Seattle NowWhile the community-led preservation movement of the 1960s and 1970s strove to preserve Pioneer Square and the stories within this distinctive area, early efforts failed to fully recognize marginalized communities that contributed to the history of Pioneer Square and Seattle, such as Native Americans, LGB communities, Asian Americans, and the working class. Around this same time, the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian American Experience was opened to share Asian American stories and enhance the vibrancy of the Chinatown-International District. It is now an affiliated area of the National Park System that connects people to the dynamic history, cultures, and art of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders through vivid storytelling and inspiring experiences to advance racial and social equity. In the 1980s Microsoft Corporation led the way in Seattle's becoming a world-wide computer technology center. The city's port evolved into a major depot for container ships, a grain exporting center, and in the early 2000s a summer base for Alaska-bound cruise ships. The University of Washington advanced to leadership among the country's research institutions. By 2021, with a population of more than 755,000, the city is the core of a growing metropolitan area totaling some 4 million people. Seattle continues to be a gateway for thousands of people. The three designated sites of Seattle Area National Park Sites (Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park - Seattle; the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial; and the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience) are distinct, however; collectively, the sites offer gateways into understanding the interconnectedness between people, places, and shared histories of the area. Over time, Seattle has become a confluence of communities resulting from significant movements of people, both forced and voluntary, transforming the city into a tapestry of cultures, societies, economics, and histories. |

Last updated: September 17, 2025