|

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GRSM) encompasses just over 2,900 miles of cold and coolwater streams, of which an estimated 20% are large enough to support trout populations. Rainbow trout occupy 15.2% of these streams followed by brook trout which are found in 8.6% of the streams and brown trout which are found in 4.6% of the streams. The National Park Service (NPS) is entrusted with management of these populations in order to protect and preserve them for present and future generations. In order to do so, the NPS monitors fish populations throughout the park on an annual basis. Many environmental factors influence trout population levels throughout GRSM. Through countless survey's and data collection, park biologists have been able to identify what drives these population trends. Surveying encompasses more than just the fish in the stream;it involves influences from all environmental aspects of the park itself.

NPS photo Brook Trout

Given the boulders and steep gradients of GRSM streams, backpack electrofishing using the 3-pass depletion methodology proves most effective to sample fish populations. The 3-pass depletion methodology blocks off a 100-meter section of stream and electrofishes through it three times, which typically results in removing 60-70% of the population. The fish are temporarily stunned, netted and placed in buckets of water. Once the fish are counted, weighed and total lengths measured, they are returned to the stream section from where they came. This data provides an insight into the overall density of species in an area of stream from year to year, among streams in the park and among streams across the country.

Using this sampling method, biologists have determined that GRSM brook and rainbow trout only live for about 3-4 years, reach a maximum size of 9-12 inches and annual mortality rates for adults range from 55% to 70%. The high mortality and short lifespan are a result of low productivity streams, which have a limited food supply. The lowest food supply typically occurs in the summer when warm water temperatures increase trout metabolic rates, causing them to burn more energy and lose weight. Many cannot take in enough food to maintain their metabolic rate, lose weight and may die. Brown trout live longer and grow larger as they switch to a mostly fish diet at about 8 inches in length, with the protein source providing better growth. Different species of trout inhabit and co-inhabit different elevation levels throughout the park. Brook trout habitat consists of the upper elevation bands (>3,500 feet), which puts them at risk to acid deposition and low productivity of food sources. In fact, at least 7 brook trout populations have disappeared in the last 30 years as a direct result reduced stream pH (average pH<6.0) due to acid deposition in these headwater areas.

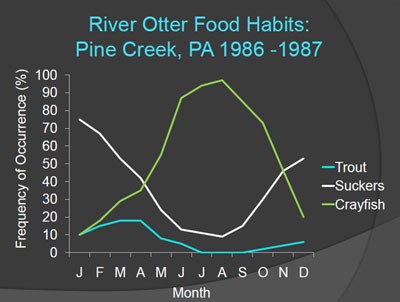

Otters

Otters were reintroduced to the park in 1992. Many anglers have blamed these animals for the decline of trout population through the park. Scat samples collected in 1986 were analyzed for specific content. The results yielded that "Crayfish occurred in 95% of all samples, followed by fish at 90%. Major fish species eaten were white suckers (57%), stonerollers (50%) and northern hogsuckers (40%). No specific size selection of fish was found. Other food items identified included frogs, turtles, salamanders and insects." (Griess , 1987)

Anglers

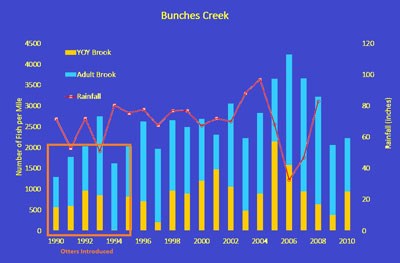

Fishing is a major year–round recreational activity within GRSM. Angler creel surveys have been conducted in GRSM since the 1950's and indicate that anglers catch about per hour and harvest per hour. Angler harvest rates have dedclined since the 1950's as more angler now primarily fish for fun and to experience nature rather than for food as they did in the 1950's era. A recent study on brook trout fishing looked at two sets of streams and compared population dynamics of brook trout in each group. One group of streams was open to fishing and one was closed;pre-fishing and fishing periods were surveyed over the course of a 3-year period. Biologists assessed the density of adult and young of year (YOY) and found that there were no significant declines in the measured densities. In fact, anglers had no impacts on any population metrics in the study, indicating legal fishing does not harm wild brook trout populations within GRSM.

Floods and Droughts

Fish populations are most impacted by major spring floods and summer droughts. Extreme flooding can greatly decrease the number of YOY and redds as the eggs and small fish have little to no ability to escape the heavy stream flows. Debris flow is the leading destructor of viable habitat. During the floods debris such as trees and substrate can scour the stream channel which removes the current YOY age class and destroys nesting sites. Droughts account for reduced recruitment possibly due to decreased spawning habitat. During these droughts the volume of the stream and temperature change can put a large stress on current populations by increasing competition for food sources and increased predation. These events account as the highest impact to population trends.

Conclusion

Of all the factors affecting the trout population dynamics, it appears the environmental factors affect trout population dynamics the most;anglers and otters have minimal impacts on the populations. Sampling these areas better helps us to understand and manage populations within the park. Disproving the misconceptions through sound data collection better provides information to properly monitor and make decisions within a population. Good fish population data and complimentary environmental data (air, water quality) will help biologists better understand how environmental factors influence fish populations. These data will provide data to policy makers who can guide air and water quality laws to further protect and preserve our national parks for future generations to enjoy.

Smallmouth Bass Fishing in the Park

Prepared by Josh Lynn.

|

Last updated: August 18, 2015