|

Biologists and geneticists are collaboratively studying the genetic composition of several fish populations in the park, including brook trout, Citico darters and 2 listed madtom (Noturus sp.) to better preserve these fragile, yet important species to the many streams of Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GRSMNP). Southern Appalachian Brook Trout (SABT) are a regional strain of brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) common throughout the Park that have a unique and complex genetic history.

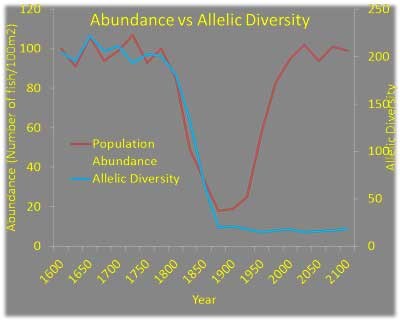

Significant differences from Northern brook trout are the result of sustained isolation during the last major glaciation of North America. Factors that further isolated SABT and increased their genetic differences include degradation and loss of habitat due to extensive logging, further habitat loss due to the stocking of introduction of rainbow trout and hatchery-sourced Northern brook trout, isolation above natural barriers (i.e. cascades and waterfalls) and acid deposition at high elevations. One of the detrimental side effects from long term isolation is decreased genetic diversity within these sub-populations, which leads to the overall species inability to adapt to changes in environmental conditions

NPS Photo Other diverse fish groups, such as cutthroat trout and bluegill, have been split into separately named and independently managed species based on smaller differences in their genetic structure. Although the genetic differences within SABT populations from multiple streams in the Park have been found to be far greater, they are still named and managed as a singular species at this time.

Fisheries biologists first discovered how truly unique SABT populations were within the Park during restoration of Lynn Camp and Leconte Creek where invasive rainbow trout (Onchorynchus mykiss) were removed and wild, native SABT sourced from several streams in the Park were stocked in after.

Ian and Charity Rutter photo Management of SABT within the Park now focuses on recognizing the true individuality of each streams populations and looking at long term methods to maintain their genetic diversity and integrity by increasing stream connectivity throughout a watershed. Abrams Creek on the South-West side of the GRSMNP is one of the most specious and diverse watersheds in the Park where the Federally listed Citico darter (Etheostoma sitikuense) and two small catfish species, the yellowfin madtom (Noturus flavipinnis) and the Smoky madtom (Noturus baileyi) are found.

Conservation Fisheries, Inc. photo. Like the SABT, habitat fragmentation due to the isolation of Abrams and Citico Creek and Tellico River created by Chilhowee Dam, could result in similar isolation issues. These small fish are unable to travel between creeks and reproduce as they historically did and this could negatively impact their genetics. Fisheries staff in the Park has learned from SABT restoration efforts of the importance of genetics in creating viable populations and are using effective methods to truly restore the fish of Abrams Creek.

Why is maintaining genetic health important? Populations with greater genetic diversity are better adapted to persist given the various environmental stressors (i.e. drought, flood, climate change), diseases and human stressors (i.e. pollution, invasive species) that they may be exposed to in upcoming years. Genetic diversity is like "genetic insurance" that will increase the populations chances of surviving these stressors and persisting into the future.

In partnership with several agencies (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, Conservation Fisheries, Inc.), fisheries personnel will be collecting and transferring Citico darters and madtoms from Abrams Creek to other isolated watersheds they are currently or historically found in to maintain and perhaps improve the genetic diversity of these species on a larger scale throughout their range.

Moving as little as 5% of each of these species populations per year to each of these isolated creeks will maintain their genetic diversity and overall stability for years to come. Genetics is rapidly expanding within the natural resources field and allows fisheries biologists within the GRSMNP to better manage the Parks populations of Southern Appalachian Brook Trout, Citico darters and native madtoms so that they are here for the enjoyment of present and future generations.

Created by Eric Malone and Kenneth Lingerfelt.

Suggested Reading for Further Information:

https://irma.nps.gov/App/Reference/Profile/2220949

Richards, Amber L., King, Tim L., Lubinksi, Barbara A., Moore, Stephen E., Kulp, Matthew A., Webb, Lisa S. 2008. Characterization of the Genetic Structure among Brook Trout in LeConte Creek, Tennessee. Proc. Annu. SEAFWA 195-202.

|

Last updated: August 18, 2015