NPS photo. It’s the middle of a frigid October night, and we’ve climbed on the roof of Kuwohi Tower. Fog swirls tight around us, nosing its way through our jackets and hiding the sudden edges of our perch. We hurriedly open equipment cases and hand sensors, cameras, and tripods to Kate Magargal, the technician from the NPS Night Sky Program. When she’s done assembling her instruments, we stand and shiver and wait for the fog to clear, so we can take images of how dark the night sky is—or isn’t—over Great Smoky Mountains National Park. When Thomas Edison invented the light bulb, he probably could not have imagined the pulsing glowing cities and veins of highways lit with headlights connecting them. And few people would have imagined a downside to more light. Yet the constant shine of light over much of the globe had has consequences, both visible and invisible. On humid nights, we can see a tangerine glow in the sky rather than stars. City and traffic lights illuminate the night sky, masking the light from stars and moon and limiting our ability to see safely. These are tangible results of light, and are so common we hardly remark upon them, except in their absence.

C. Mayhew & R. Simmon, NASA, NOAA, NGDC. Light at night has invisible impacts, too. All over the world, millions of artificial lights spilling into the sky change the way animals—including humans—behave and how healthy they are, both on the individual and population level. Biologists call the extra light that spills into the sky ecological light pollution. Monitoring light as part of a “threat assessment” program is a relatively new idea, because we’re just realizing all of the ecological impacts that artificial light at night can have. A new discipline—Scotobiology—is the study of light as related to biological processes. Scotobiological studies show that artificial light at night has impacts on

NPS photo. Light Nights in the National Parks The dark skies of many national parks are disappearing. Monitoring helps us keep an eye on how light our skies are becoming with surrounding human development, how animal behavior changes with more light, and how we can plan to keep our dark skies dark in the future. The program to monitor our night skies began in Utah and is now based in Ft Collins at Colorado State University. This program is the first in the country to measure light from the ground. Traditionally, scientists measure light from space using satellite imagery. But this doesn’t take into account perspectives from certain places on the ground, which is how people and other animals experience the light. Night Skies Program technicians use a CCD camera, a sturdier field version of what astronomers use in a planetarium. This digital camera helps scientists estimate how much light hits each pixel on the image of the sky. The light is measured in magnitudes (intensity of the light’s brightness) per arcsecond (a sliver of space cut out of the circular “pie” of the sky, looking up). As the Night Sky Monitoring technician, Kate visits about 30 of the 50 national parks enrolled in the Night Sky Monitoring Program each year. While more Western parks are represented now, the program is adding Eastern units where there are more bright cities close to parks.

NPS photo. Which parks are the darkest? Out of 112 parks measured, 29 were tied for the darkest. These included Badlands National Park, Big Bend National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Chiricahua National Monument, Glacier National Park, Isle Royale National Park; Lassen Volcanic National Park, and Death Valley National Park. Park units closest to—sometimes in—cities are the brightest. They include the Statue of Liberty National Monument, Rock Creek Park, Muir Woods National Monument, the Presidio of San Francisco, and Independence National Historical Park.

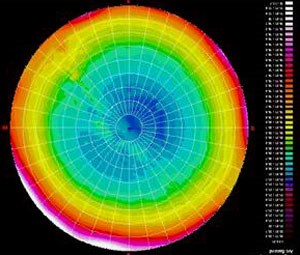

NPS image. How dark are the Smokies? The Smokies are fairly dark, probably because the nearest large cities are 40 to 100 miles away. The Smokies had similar darkness measures as Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, Assateague Island in Maryland/Virginia, and Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. In the Smokies, we can see bright (shown in white) light coming from nearby Knoxville, Maryville, Pigeon Forge and development in Sevier County, and from more distant Waynesville and Asheville in North Carolina, and Atlanta about 140 miles (as the crow flies, or, in this case, as light shines) in Georgia. This light can have complex changes on the animals—and people—that as we know them in the Great Smoky Mountains.

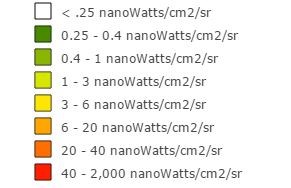

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park offers the best view of the night sky in the area. The parks vastness, high peaks and numerous scenic vistas offer visitors a unique opportunity to observe the landscape above unencumbered by artificial light. To illustrate how the parks night sky viewshed differs from surrounding urban areas, the map below depicts artificial radiance measured by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radimeter Suite (VIIRS) in 2012.

NPS How Do We Reduce Light Pollution? We can immediately fix light pollution by turning unused lights off, adding a light shade outdoors, and adding motion sensors to lights so they only shine when they're needed.

Photo (C) Todd Carlson. Used with permission. Reducing light pollution in our communities will help us:

Photo (C) Todd Carlson. Used with permission.

Initiatives such as the National Park service’s Night Skies Program will help us understand how much artificial light parks receive, and help us preserve unimpaired dark skies for the future. Return to the Air above and beyond the Smokies page. |

Last updated: May 9, 2025