NPS Photo / S. Tevebaugh Yaa Naa Néx KootéeyaaThe Healing Totem PoleYaa Naa Néx Kootéeyaa (Yah Nah NEX Koo-TEA-Uh), the Healing Totem Pole, stands at the head of the public dock in Bartlett Cove, Glacier Bay National Park. Designed by tribal elders, culture bearers, artists and National Park Service staff, it compresses centuries of history into 20 feet of yellow cedar. It tells the story of the evolving relationship between the National Park Service and the Hoonah Indian Association, the federally recognized tribal government of the Huna Łingít clans. Mixing traditional form line design and modern artistic representations, it depicts the Huna Łingít’s tragic migration from Glacier Bay Homeland, a painful period of alienation, and more recent collaborative efforts between the tribe and the NPS. The Healing Totem Pole was specifically designed not only to relate the difficult history between NPS and the Huna Łingít, but also to relay the history of people working to overcome past hurts and heal. See additional photos of the Healing Totem Pole, including photos from the dedication ceremony, in this photo gallery

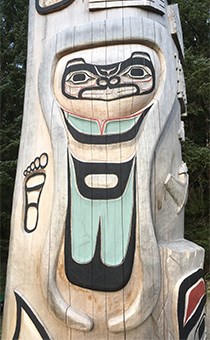

NPS Photos / I. Nixon The form line design in the lower section of the pole represents the spirit of the glacier that overran the main Łingít villages in Glacier Bay during the Little Ice Age, around 1750. Łingít elders say the glacier advanced “as fast as a running dog,” crushing the clan houses that lined the shores. The clans fled for safer places far from the glacier. Elders say this was a very sad and difficult time – the people had to adjust to new food sources, new territories, starvation and disease.

The form line design on this side of the pole represents Lituya Bay, the territory of the T’akdeintaan (Duck-dain-tahn) Clan. About the same time as the glacial advance in Glacier Bay proper, the villages in Lituya Bay were destroyed by a giant tsunami caused by a landslide.

After the glacier retreated, sometime in the late 1700’s, Łingít from Hoonah returned to Glacier Bay, building a summer village called Gaathéeni (Got-heen-ee), which means Sockeye River. For many years, the Huna Łingít travelled back and forth between this seasonal village, other summer fish camps, and the permanent settlement in Hoonah. These figures represent the canoes the people traveled in and the fish racks that used to line the shoreline of Bartlett Cove. In 1925, Glacier Bay became a National Monument. Most Łingít did not understand what that meant; in fact, many elders only spoke Łingít and did not even speak English well and certainly did not read the formal letters and newspaper articles that described the new National Monument. For a period of time, the Huna Łingít continued to visit Homeland and harvest the foods that had always been harvested. However, over time, the National Park Service began enforcing laws and regulations that made some traditional practices illegal. For example, it was no longer legal to hunt seals or gather seagull eggs in Glacier Bay.

The Huna Łingít call this period the Second Little Ice Age. One elder described the federal government as a “faceless, soulless being with too many hands.” The chains represent the Huna people’s feeling of being barred from Homeland, traditional foods, and the ancestors they believe remain in Homeland. The Łingít felt that the federal government in Washington, DC did not understand the importance of their traditional way of life.

Elders were heartbroken for many years. The tears along the pole represent all the treasures the Huna Łingít felt they had lost - homes, halibut, gumboots, etc.

About 25 years ago, the National Park Service began talking with the tribal government, Huna elders, and other tribal members about how to better facilitate the enduring connection between the Huna Łingít and their Homeland while strengthening our relationships. Groups of Huna elders and culture bearers travelled to Bartlett Cove for meetings, and NPS staff made frequent visits to Hoonah – figuratively travelling across rough waters to find common ground. In 1995, the NPS signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Hoonah Indian Association agreeing that both entities would work together to mend our relationship and restore the Huna people to Glacier Bay. The Huna Łingít called this process Woosh ji.een (Woosh-gee-een) – working together, (it literally means “hands together”). Over the intervening years, NPS and HIA have collaborated on numerous projects and programs that reconnect tribal members to their Ancestral Homeland. We have cooperatively planned Journey to Homeland Trips, successfully reauthorized gull egg harvest, and most importantly, we built a Tribal House together. In 2016, two handcrafted dugout canoes journeyed from Hoonah to Glacier Bay Homeland across much less turbulent waters to dedicate Xunaa Shuká Hít (Huna Ancestors’ House). Today, we (NPS flat hat and Tribal cedar bark hat) “hold the Tribal House up” together - cooperatively managing it through a Cooperative Agreement with the Hoonah Indian Association. The Tribal House supports traditional ceremonies, gatherings, workshops, camps, and meetings and is open to park visitors who want to learn more about Łingít culture.

The footprints running the length of the totem remind us that the Huna clans have returned over and over again to “walk in the footsteps of their ancestors.”

|

Last updated: April 22, 2025