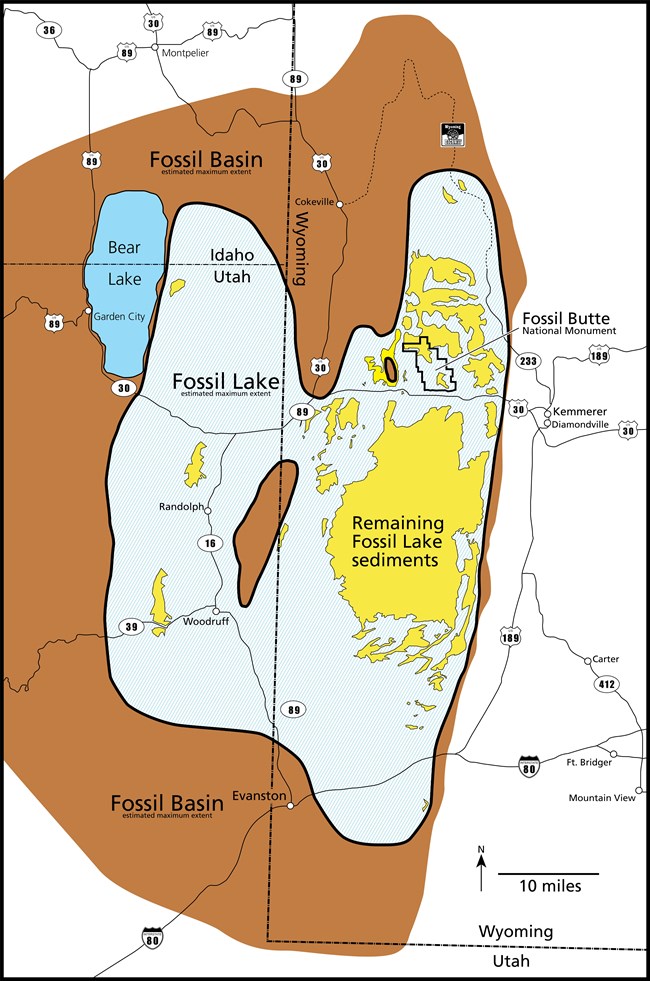

NPS image The layered rock of the Green River Formation is a historical record of three former lakes: Fossil Lake, Lake Gosiute, and Lake Uinta. These lakes once covered large parts of present-day Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. Fossil Lake was the smallest. Oriented on a north south trend, its length was about twice its width. Never more than 100 feet deep, it covered around 1500 square miles at its maximum. The depth, size, and shape would have varied considerably during the lake’s existence. Today, Fossil Butte National Monument protects nearly 13 square miles of land in southwestern Wyoming. Here the memory of Fossil Lake exists only in cliff-forming carbonates that cap the more gently sloping shoulders of the flat-topped ridges. These top-most rock layers were once mud at the lake’s bottom. Their calcium and magnesium-rich chemistry attests to the alkalinity of the lake water.

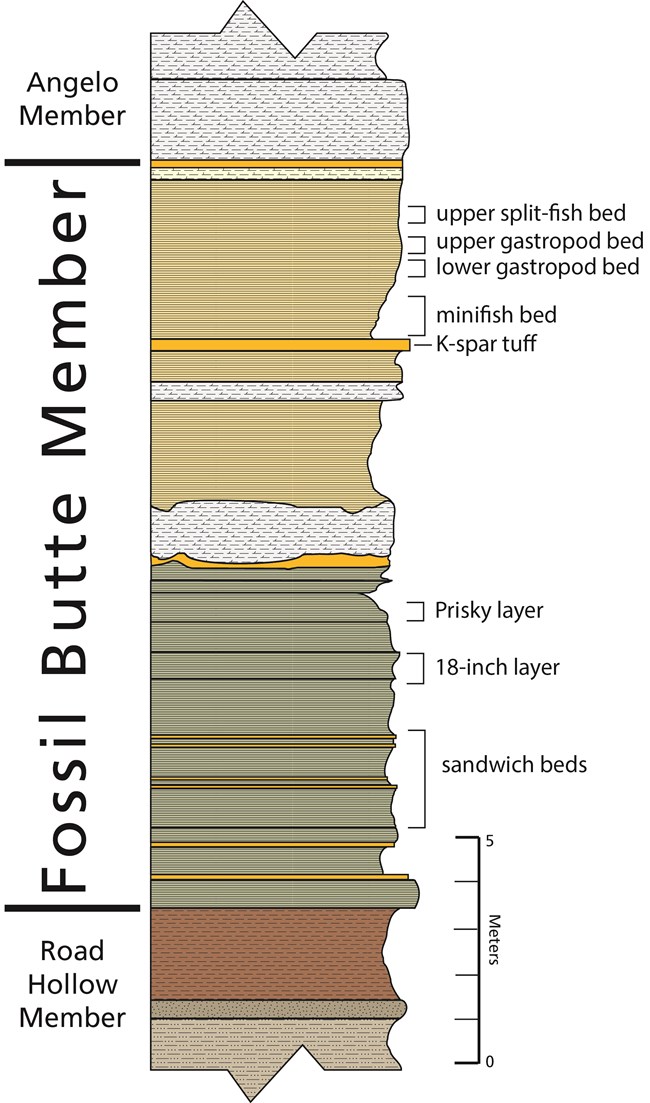

NPS image The Green River Formation within the Fossil Lake basin is sub-divided into three members. They are from bottom (oldest) to top (youngest), the Road Hollow, Fossil Butte, and Angelo members. The Road Hollow Member is the early formative stage in the lake’s existence when sedimentation varied between river-delivered and lake-formed. During the Fossil Butte Member time, the lake was at its deepest and most expansive. Lake-precipitated calcite-rich sediment predominated. This is also the most productive fossil-bearing unit. Finally, the Angelo Member finds the lake’s fortunes diminished. It was shrinking, shallowing and becoming saltier as evaporation outpaced water supply. Its deposits are rich in dolomite, chert, halite, and trona. The ledge-forming middle third of these picturesque escarpments is the Fossil Butte Member. Composed mostly of laminated calcite-rich mudstone, this unit is world renowned for the preservation, abundance, and diversity of its fossils. Within this member, many of the most productive fossil-bearing layers have informal names like sandwich bed horizon, 18-inch layer, minifish bed, and gastropod bed that are more descriptive than scientific. The sandwich bed is composed of two closely spaced volcanic ashes (slices of bread) between which you find alternating limestone (turkey) and kerogen (roast beef) laminations. The average thickness of the 18-inch layer is, you guessed it, 18 inches. It produces the largest and best-preserved fossils. In the minifish bed, the fossils are more abundant, albeit much smaller on average. Snails are very common in the gastropod bed.

NPS / John Collins The more gently sloping base of the flat-topped ridges is the Main Body of the Wasatch Formation. Its red, tan, and gray sedimentary rock, deposited as stream gravel, sand, silt, and clay, also has fossils. This includes teeth and bone fragments from at least 46 different kinds of land mammals. Among these are the hippo-like Coryphodon and the diminutive primate Cantius. As has occasionally happened with the early horse Protorohippus venticolum and lemur-like Apatemys chardini, discovery of more complete specimens within the Green River Formation is possible given that Wasatch Formation deposition continued at the same time. Although much less common, these remains only needed to wash into the lake shortly after death to fossilize intact. Compressional forces that pushed up the modern Rocky Mountains warped the crust to the west downward in places. This created shallow basins that captured rainfall and river flow to form lakes. One such basin, known as Fossil Basin, became home to Fossil Lake. After millions of years, the lakes vanished as these forces waned and the basins filled with sediment. Later, these same areas experienced slow regional uplift. This allowed meandering rivers to transform a high, featureless plain into a landscape of broad valleys and flat-topped ridges. Within Fossil Basin today, the elevation of the valleys and ridges average 6600 and 7600 feet respectively.

NPS photo |

Last updated: April 29, 2025