Research Report

Saving the Stones: An International Practical Conservation Training Internship

by Shelley-Anne Peleg

Saving the Stones is a five-month internship in historical and archeological conservation. It is sponsored by the Israel National Commission for UNESCO and ICOMOS Israel. The program is run by the International Conservation Center in Old Acre (ICC), and is a joint project of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), the Old Acre Development Company, and the Acre Municipality. The ICC is aptly located in Old Acre, a place described as "a veritable living laboratory for the study and practice of conserving historic sites and structures as well as researching oral history and traditional cultural aspects of the city."(1)

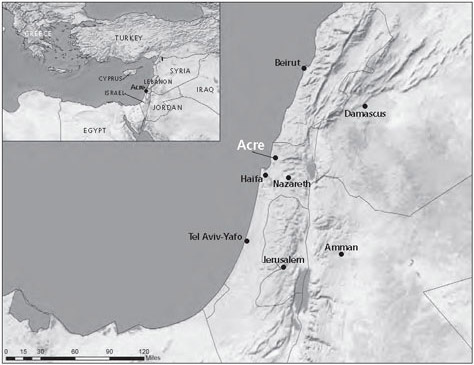

Acre is the capital of Western Galilee and is located at the northern edge of Haifa Bay. (Figure 1) A walled port city, Acre traces its settlement back to the Phoenician period. The first Christian pilgrims stopped in Acre en route to Jerusalem, and soon the construction of churches and monasteries followed. Acre was a principal port, and this sustained it during the years the city was controlled by the Caliphate of Cairo. Its fortunes recovered in the 10th and 11th centuries, particularly after the city fell to the Crusaders in 1104. Its walls were rebuilt. A new model of settlement, with defined quarters, evolved within and near the walls and the city flourished as a confluence of eastern and western cultures.

|

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Acre at the northern edge of Haifa Bay. (Courtesy of Deidre McCarthy, CRGIS, National Park Service, 2010.) |

After the Third Crusade, led by Richard the Lion Heart in 1191, Acre rose to new prominence, becoming the capital of the Crusader kingdom. Significant remains from this epoch (1104-1291) are found above and below the present street level, albeit mostly subterranean, and illustrate the shift in western architectural taste from the Romanesque to the Gothic. Significantly, the evidence of the 12th- and 13th-century Crusader town found in Acre today provides a snapshot of the layout and structures of the capital of the medieval-period kingdom of Jerusalem.(2)

Crusader Acre fell to the Arabs in 1291, and over the next several centuries Acre was largely abandoned. The Ottoman period (1517-1917) saw renewed activity in Acre, but not until the 18th century. The Ottomans built their city over top of the Crusader town, preserving its plan and many of its artifacts in the foundations of the new buildings. The Ottomans created a metropolitan system of alleyways, courtyards, and squares in keeping with Moslem societal norms and melding the port with civic and ecclesiastical buildings, khans (rest houses), markets, shops, and residential quarters.(3)

Acre currently appears as an Ottoman-era walled town complete with typical urban components dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the citadel, mosques, and baths. These staples of Ottoman architecture were erected on top of the underlying Crusader-era structures. And it is this combination of an 18th- and 19th-century Moslem fortified town with substantial artifacts from the medieval Crusader town that prompted Acre's recognition as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2001.(4)

The richness of Acre's past, with its layers of history preserved in the archeological record from the early settlement and Roman period through the Crusades and Ottoman Empire, make the city an excellent teaching tool for conservationists. Work on the city's historic fabric also raises awareness of archeological practice and how archeological evidence can inform present-day perceptions of life lived in different times, through varying religious movements, and under aegis of alternating political and military powers. Making the archeological work public also encourages heritage tourism, adding to the popular appeal of Acre's beaches, and garners support for the ongoing investigations by including the public in the discovery and discussion of the evidence.(5) Saving the Stones plays an integral role in this effort.

Beginning in 2009, the Saving the Stones conservation internship features the study of ancient building technologies and materials, tutelage and training from leading Israeli conservation specialists and archeologists, and an immersion into the nations, cultures, and religious movements that swept over Acre. The interns conduct surveys and produce documentation for current conservation projects, make study visits to various sites with Israeli conservationists, and develop their architectural drawing, photography, and computer skills. Educational programs focusing on Israeli architecture and Acre's heritage enhance the interns' practical experience of conservation work on-site (Figure 2). Because the internship spans five months, the participants become part of the community in Acre, learning something of the Hebrew language and taking in cultural events. The program is open to English-speaking people from all over the world.

The program in 2010 included eight international participants and two Israelis. Their projects ranged from the broad urban survey to the tightly focused conservation of specific building elements. They worked to record the Ottoman walls and document the Sabil Al-Jazzar (an Ottoman-era public fountain) and the cisterns under the Al-Jazzar Mosque. Other broad study topics included the research and documentation of conservation planning during the British Mandate (1918-1948) and an urban typology for the new city. More specialized study was done on historic mortars and mosaic conservation in Israel. The participants also prepared conservation plans for various sites in Acre, thereby guiding efforts to save the stones long after their internships concluded.

About the Author

Shelley-Anne Peleg is the Director of the International Conservation Center and she can be reached at shelley@iccakko.org.

Notes

1. Summary statement from www.antiquities.org.il/akko/information11.asp,accessed on June 21, 2010.

2. Historical synopsis from http://whc.unesco.org/pg.cfm?cid=31&id_site=1042, accessed on July 8, 2010.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. In the United States, the restoration of Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest was (and is still) done while the museum was open to the public, successfully combining the architectural research and archeological excavations with tourism to include the public in the process. Field schools for architecture and archeology train the next generation in current methods and practice, inviting comparisons to the much larger program in Acre. See www.poplarforest.org.