Article

Beyond the Bitumen: Australia's Stuart Highway and the Cultural Construction of a Road

by Rosemary Kerr

"The Stuart Highway has about it an aura of stark heroism, of haunting romance. It's our equivalent of ancient spice routes, of the Canadian Pacific Railway, of the Grand Trunk Road, prizing riches from the uninhabitable."(1) These words, by Australian travel writer, Keith Willey, convey something of the romanticism surrounding Australia's Stuart Highway. Australia's first transcontinental highway, better known as simply "The Track" or "The Bitumen," connects Port Augusta, near Adelaide on the southern coastline, to Darwin in the tropical north, through Central Australia and the Great Australian Desert, a distance of almost 1,800 miles. Named in honor of explorer, John McDouall Stuart, whose route it approximates; constructed and improved during World War II as one of the nation's key strategic defense roads, it now forms part of Australia's National Highway System, a series of roads encircling and bisecting the nation, connecting all the states and territories and Australia's largest and most important cities. As Willey's quote suggests, however, roads are cultural landscapes, constructed both physically and imaginatively. As valuable cultural resources, they are capable of articulating much about the heritage of a locality, region, or nation, yet they also present particular challenges for cultural heritage management. Roads embody elements of both the natural and cultural environment; they often extend over vast geographic distances; and their meanings and significance are not static, or tied to a particular historical moment, but are constantly being recreated and overlaid through journeys along the route over time, as past and present interact.

Certain roads become nationally significant not only because of their strategic importance or engineering excellence, but because they have assumed a unique place in the national imagination. Such significance is also "constructed" through a dynamic process of interaction between the route's history; its physicality; visions of planners and promoters; travelers' experiences; and representations in popular culture. Yet, it is these intangible qualities that are most difficult to incorporate in preservation and interpretation strategies. This article explores the cultural construction and interpretation of one of Australia's most nationally significant routes—the Stuart Highway.

Over the past decade, the heritage profession internationally, led by American scholars and practitioners,(2) has demonstrated a growing interest in the identification, interpretation, and preservation of roads and "cultural routes"(3) as heritage resources. The Australian heritage community has also shown a strong desire to engage with the study of roads as holistic cultural landscapes, although federal, state, territory, and local governments have been slow to come to grips with these challenges.(4) When government agencies attempt to address road heritage, studies are often managed and driven from an archeological, architectural, or engineering perspective, with the main focus concentrating on material and aesthetic qualities; on specific items of road infrastructure such as bridges and culverts; or on particular sites of built and natural heritage along the road corridor. Roads and routes, however, are so much more than the sum of their parts. This study approaches the Stuart Highway from the perspective of the cultural historian. Through an integrated analysis of the route's environment, physicality, historical documentary evidence, tourism literature, travelers' narratives, and representations in popular culture, it attempts to explain the evolution of the Stuart Highway's cultural significance for Australia and what that might reveal about the broader national culture, including some of its underlying mythologies. Looking beyond material fabric and specific sites to the multiple layers of meanings imbued in the route itself offers a deeper understanding of the processes that have constructed the road as both a physical and imagined space. Such an approach may also prove useful for interpretation and preservation strategies.

A rich body of literature exists in the US regarding the significance of "the road" in national culture(5) and some of these works provide a useful starting point for thinking about the road in national imagination. Karl Raitz's study of America's first federally funded highway, the National Road, founded in 1806, argues that the route was perhaps more important symbolically than functionally as it both figuratively and literally connected East and West, and divided North and South. The National Road was to provide an overland link between East Coast cities and the old Northwest Territory and emerging Middle West—the vast, fertile country which lay beyond the Appalachian Mountains and north of the Ohio River. In the era following the American Revolution, waves of immigrants flowed westward along "The Road" as it was known, as Americans began to look towards the romanticized West as the land of opportunity—their Manifest Destiny. "The Road" symbolized the ideal of a rural, agrarian artisan society extending across the frontier.(6)

Just over a century later, the Lincoln Highway, America's first coast-to-coast all-weather highway from New York to San Francisco, was heralded as follows:

It is a name to conjure with. It calls to the heroic. It enrols a mighty panorama of fields and woodlands, of humble cabins and triumphant farm homes…And because it binds together all these wonders and sweeps forward until it touches the end of the earth and the beginning of the sea it is to be named the Lincoln Highway.(7) |

From its inception, the Lincoln Highway evoked the promise of binding the nation from East to West, appealing to the ideals of democracy that its name implies, linking all of America for all Americans, enabling ordinary citizens to make their own transcontinental journey; "tracing the footsteps of the pioneer and following the path of the frontier as it moved ever westward."(8) As Drake Hokanson states, Americans have long been fascinated by the idea of spanning the continent, and this has been a source of national pride since the days of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and an ingrained part of national consciousness.(9)

In his cultural history of Route 66—America's, and perhaps the world's, most iconic road—Peter Dedek argues that a road has both a material and symbolic history. In attempting to account for the road's iconic status, he points to the Route's symbolism of the "Old West"; the flight from adversity, represented most powerfully by the Depression era "dust bowl" migrants immortalized in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath; and the power and freedom of the private automobile. Dedek describes Route 66 as a "state of mind" evoking images, ideals, and nostalgic experiences, and in driving the route one encounters multiple layers of memory, history, and myth.(10)

The south-north transcontinental crossing and the round-Australia "lap" on National Highway 1 (11) have captured the Australian national imagination in a similar way to the East-West crossing in American culture. Australia's National Highway has been described as "revealing the profile of a nation," traveling to the "heart and mind of Australia."(12) The Stuart Highway is that heart's main artery and the route is one of multi-layered meanings and stories with a deep history.

For tens of thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, the entire Australian continent was already inscribed with the routes traveled by Aboriginal inhabitants. Aboriginal peoples had an intimate and spiritual connection to the land based on a sense of belonging rather than possession, and Dreamtime legends that tell of totemic ancestors' travels and exploits, explain how the landscape and its major topographical features, including water sources, were created as well as providing navigational markers. These "Dreaming tracks" or "songlines," criss-crossed the continent and formed important routes of communication along which people, goods, and knowledge flowed across vast distances; and were celebrated in cycles of songs, stories, and rituals. The various groups or "tribes" were differentiated by linguistic and geographic boundaries, and the region of Central Australia, around Alice Springs and north towards Tennant Creek was the territory of the Arrernte or Aranda peoples.

One of the Aranda Dreaming ancestors is the native cat (tjilpa) and its songline is among the longest, traversing all of Central Australia from Port Augusta on "the south coast, where seagulls lived, ever onwards to the north coast, the crocodile's home."(13) The myth tells of how one of the tjilpa hordes travelled from Port Augusta and entered the Aranda territory at Ilbila, a series of springs west of Alice Springs. After the tjilpa men had gone on, night overspread the land behind them and they laid down a great expanse of sandhills, covered with stands of desert oaks as a barrier. This describes the topography of the south-western Northern Territory: thick mulga growing around the hills bordered by waterless sandhills.(14) While the Aranda-speaking territory included some of the best-watered and more fertile regions of Central Australia, the Aranda engaged in trade and ceremonial exchanges with neighboring groups in arid areas, including the Alyawarre and the Northern and Eastern Arrernte, the Wangkangurru of the southern Simpson Desert and the Arabana to the west of Lake Eyre. The groups gathered at places such as the Native Cat (Urumpele) site, an important ceremonial area roughly midway between Alice Springs and Lake Eyre.(15)

Arabana and Wangkangurru peoples were connected to the mound spring country of northern South Australia. Mound springs are the natural outlets for the pressurized ground water of the Great Artesian Basin and occur around its margins as the only permanent drinkable water in some of Australia's most inhospitable regions characterized by sand ridge and stony deserts; extreme annual temperature ranges and low, erratic rainfall. The springs featured prominently in many Arabana and Wangkangurru myths and songlines, with individual springs taking on varying roles, from simple watering points to locations where important actions or incidents associated with major dreaming cycles took place.(16) Thus, in Aboriginal culture, the entire Australian landscape is understood as a network of stories,(17) based on journeyings; but the knowledge embedded within those stories laid the foundations for the pathways of later European journeys.

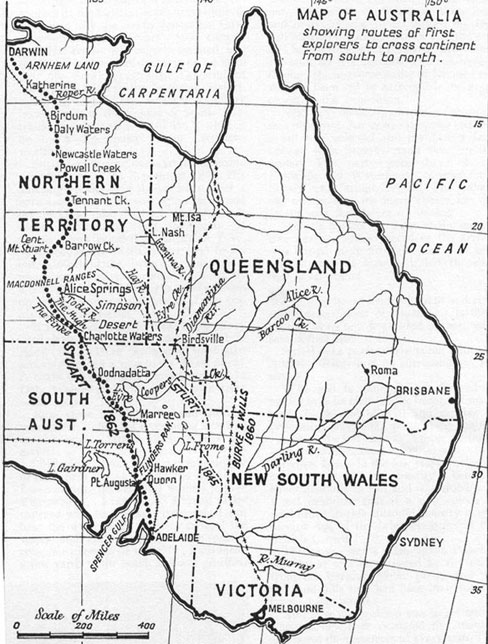

From the earliest days of British settlement, Australia's "dead heart" held a fascination. Speculation about what lay at the center of the continent, including rumors about the possibility of a vast inland sea, and the need to find productive land, motivated several exploratory expeditions in the mid-19th century and many tried, unsuccessfully, to completely cross the vast, unknown inhospitable interior—Australia's own frontier.(18) The first to complete a south-north coast to coast crossing, through the Centre, was Scottish explorer and surveyor, John McDouall Stuart, who finally succeeded, in 1862. The Stuart Highway thus bears his name and its route roughly follows the trail that he blazed (Figure 1). Stuart's success relied on the knowledge gained from earlier expeditions,(19) including his own in 1858, 1859, and 1860, particularly regarding the location and strategic importance of water sources. Stuart's journals make several detailed references to the mound springs, invariably accompanied by observations of "native tracks" or other indications of Aboriginal presence. His party sometimes followed these tracks to water or asked the Aborigines where to find it, and they usually obliged.(20) Stuart realized that the springs were "strategic stepping stones to the interior and, ultimately, the northern shores of Australia."(21) He could not fully understand the profound significance of the pathways with which his own journey intersected, but he knew that his ultimate success depended upon them.

|

Figure 1. Map of Australia showing Stuart's route through Central Australia 1862. (J. L. Betheras, “The Story of John McDouall Stuart.” Walkabout 23:12 (1957): 31). |

Stuart nevertheless revealed an awareness of the symbolic significance of his journey through a ceremonial performance of his own. Upon reaching the Indian Ocean on the north coast on July 24, 1862, he recorded: "I dipped my feet, and washed my face and hands in the sea, as I promised the late Governor Sir Richard McDonnell I would do if I reached it."(22) Stuart's arduous journey, which almost killed him due to drought, malnutrition, scurvy, and lame horses, was a story of stoic heroism and triumph over the harsh environment, representative of the pioneering tradition of the frontier that has had such a powerful and enduring resonance in Australian cultural mythology. Australian character is said to have been formed by frontier conditions, breeding a tough, laconic, resourceful, egalitarian people, and these stories are fundamental to our national foundation myths.(23) The "frontier" has been a powerful national mythology in both America and Australia although while the American frontier is imagined as an east-west progression,(24) for Australia it could be envisaged as a movement towards the center or around the periphery as well as east-west or south-north; and this has implications for the significance of particular routes in the national imagination.

Stuart's expedition advanced geographical knowledge and reported favorably on the economic potential of the Northern Territory, and in the ensuing years pastoral stations and mining operations were established along the route. Most importantly, however, Stuart's route provided a ready-made chart for construction of the Overland Telegraph Line, which was a vital communications link between Australia and Britain.(25) The telegraph line, built between 1870 and 1872, ran for 1,800 miles from Port Augusta to Darwin, where an undersea cable connected it to Java (Indonesia) and India, thence to Britain. Australia's geographic isolation at the bottom of the world meant that mail sent by sea took months to arrive. The Overland Telegraph allowed direct communications between Australia and Britain for the first time and its construction was itself a feat of remarkable endurance and one of Australia's greatest engineering achievements.(26) The Overland Telegraph Line represented "a thread of civilization running through the desert"(27) as Morse repeater stations formed the nucleus of settlements, then towns, including Beltana, Alice Springs, Barrow Creek, and Tennant Creek.

A rough track was formed and this provided a traveling stock route as well as some direction, if not much comfort, for intrepid cyclists then motorists for whom the challenge of crossing the continent from coast to coast proved irresistible. Jerome Murif, the first cyclist to complete the south-north crossing in 1897 set off from Adelaide, after dipping the wheels of his bicycle, christened "Diamond", into the waters of the Southern Ocean. As he left, he recalled, "A glad feeling of being alive, untrammeled, free. And so we gaily sped along. It was a very dance on wheels. We are on the track at last!"(28) Murif's "track", which he also often refers to as a "road," even "highway" at times, scarcely resembled anything like a road by today's standards. He relied on the rough track of the Overland Telegraph and Great Northern Railway, begun in 1879(29); getting directions as he went from supply depots or telegraph stations. Riding or pushing his bicycle through sand and spinifex, he looked "longingly for signs of a mulga thicket", as "there…the ground will be much firmer" and "the road improves to very good."(30) In a symbolic gesture echoing that of Stuart and subsequent generations of transcontinental travelers, Murif marked the completion of his journey with another ritualistic bathing(31) of the cycle in the Arafura Sea off Palmerston, now Darwin. He saw himself as a pioneer or explorer, following in the footsteps of Stuart, opening the way for others to follow; and making the inland of Australia and its Northern Territory better known.(32)

Henry Dutton and Murray Aunger became the first to complete the south-north crossing by car in 1908, driving a British 25 horsepower Clement Talbot.(33) Aunger's account of the journey gives some indication of the hardships faced, including sandhills and dry sandy creek beds, which had to be crossed with the aid of coconut matting laid in front to provide traction for the wheels.(34) It was clear that the motorists saw themselves as engaging in a pioneering adventure, literally charting a course and taming the frontier, as Aunger wrote:

Motoring is strenuous work when you have not only to find your course through a wilderness, but make a road for your car whilst advancing, and even build your own bridges. Crossing the Warrender, we had to make a corduroy track of branches and saplings, which we cut out of the scrub, for in the bottom of the creek was a treacherous quicksand.(35) |

The Australian Motorist agreed, celebrating the significance of their achievement:

Certainly Messrs. Dutton and Aunger have opened up possibilities of a grand motor car route which will one day link up Northern and Southern Australia, leading to trade development and settlement and a shortened route to Europe.(36) |

For Dutton and Auger, and the many pioneering motorists who later followed in their trail, the Overland Telegraph Line was a landmark by which to gain their bearings, make contact with signs of "civilization" and rejoin their path, on their transcontinental journey (Figure 2). Even at this early stage, the idea had been sown that the south-north route was a "road" leading to the world beyond Australia's borders. The Telegraph Line laid the foundations for a route that has been followed by travelers ever since, often as a prelude to a journey leading beyond Australia, particularly the well-worn overland route to Europe via Asia and the subcontinent, termed the "hippy highway" due to its popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. In spite of, or perhaps because of their isolation, Australians have had a strong desire to see "the road" as extending to a world beyond our borders and the south-north transcontinental route and later Stuart Highway, has played an important role in that vision.

|

Figure 2. "On the Overland Telegraph Route," 1929. (Photographer unknown. Thornycroft Collection, Northern Territory Library. PH0676/0005.) |

In the post-World War I era, and particularly from the 1920s, great interest and enthusiasm emerged for long-distance motor journeys, particularly those which embraced the nation by encircling its perimeter and driving across the center, through the outback; and in this endeavor the south-north route figured prominently. Newspapers, motoring, and travel journals reported eagerly on the adventures of transcontinental travelers, including women such as Marion Bell, Gladys Sandford and Stella Christie, Jean Robertson, and Kathleen Howell in the late 1920s.(37)

These and many other motorists kept written and photographic journals of their trips and a highly popular genre of descriptive travel writing emerged, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, celebrating adventurous journeys and the search for the "real" Australia in highly romanticized visions of the outback as the antithesis to urban life, which for most Australians, living around the coastal fringe, was the norm. Such developments reflected anxieties and struggles within Australian culture over definitions of national character at a time when the orientation of economic and social life was shifting from a rural-pastoral base to an urban-industrialized one.(38) The vast unpopulated regions of the Australian 'frontier', including the Centre and far north had long been a source of anxiety and fears that Australians had not fully possessed the continent and there was a need for these regions to become better known, and utilized to their full potential. Georgine Clarsen argues that motor touring across and around the continent became part of a modern pioneering, nation-building project, inscribing white ownership onto the land by traversing it.(39)

The growing interest in and promotion of touring outback routes, including the north-south route, is evidenced by the publication of road guides for motorists from the late 1920s. The 1927 edition of The Tourists' Road Guide for South Australia included for the first time, a section on "the road to Darwin." The guide begins with a warning of the difficulties that lie ahead for the intrepid motorist:

At the outset it should be distinctly understood that a journey to Darwin cannot be regarded as a pleasure trip to be lightly entered upon…. [It] needs careful planning, arranging for supplies of petrol, water, oil at depots… A few strips of matting to help in crossing sandy patches are indispensable…A good driving rule to bear in mind is to keep to the most recently used track. Do not attempt to cross sandy patches on other than these used tracks… Care should also be exercised in diving through "gibber" country. For the benefit of the uninitiated, it may be explained that "gibbers" are boulders, or large stones. "Corduroy" roads are roads which have been reinforced with layers of logs, boughs, grass, wire-netting, or other material which will give a more or less firm surface for the wheels to grip.(40) |

It provides detailed descriptions of each segment of the route and it is clear that great care was needed to direct motorists as to which "track" to follow as the lack of a defined road and the proliferation of other tracks diverting to mines or pastoral stations caused great confusion. When possible, the advice is to "follow the telegraph line."(41) Yet the challenge of overcoming the hardships of the journey was one of the major attractions in attempting this route.

The north-south route, however, remained little more than a rough track until World War II, when anxieties about Australia's vulnerability to invasion escalated. The continent was particularly at risk of attack from the North, given its proximity to Asia. Now, the north–south transcontinental corridor was seen as a vital pathway in the nation's defense strategy. Hence, in early 1940, plans were drawn up for a road between Alice Springs and Birdum, capable of carrying military transport such as would be required in the event of an emergency. The approaching wet season meant that it was impossible to build a heavy military road in the time available, so the Commonwealth government formed the Allied Works Council and enlisted the state road authorities of New South Wales, Queensland, and South Australia to assist in undertaking the project. Each state had responsibility for building sections of approximately 320 miles, while the Commonwealth Postmaster-General's Department agreed to upgrade the road between Alice Springs and Tennant Creek. Crews worked around the clock in three eight-hour shifts; huge bulldozers and tractors drove side by side into the wall of scrub, with a heavy steel cable linking them to mow down the mulga, bloodwood, and mallee—obstacles standing on average 20-feet tall. Materials from the existing natural landscape formed the roadbed—bulldust covered with gravel.(42) A lightly metalled road between Tennant Creek and Birdum was completed in the record time of 90 days, with the intention of upgrading it once the wet season had passed. The route followed approximately the Overland Telegraph Line but varied by as much as eight miles from it due to the necessity for several creek crossings.(43) The completion of this section of the road in such a short time and in difficult, remote terrain was celebrated as a remarkable achievement, with the road lauded as the "Ninety Days Wonder."(44) An article in Australasian Engineer in February 1941 declared proudly:

The all-weather formed road, [which has] made Central Australia accessible from north and south throughout the year, ranks amongst the finest road construction successfully undertaken in this Continent, and for sheer speed, in view of its remoteness from supply bases, has made itself World Standard No. 1.(45) |

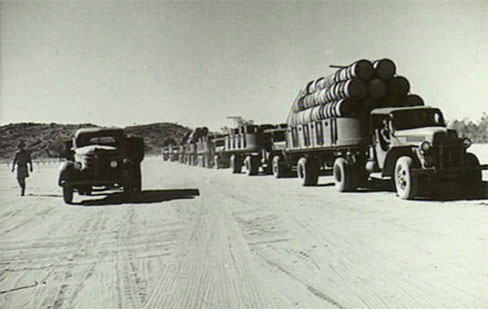

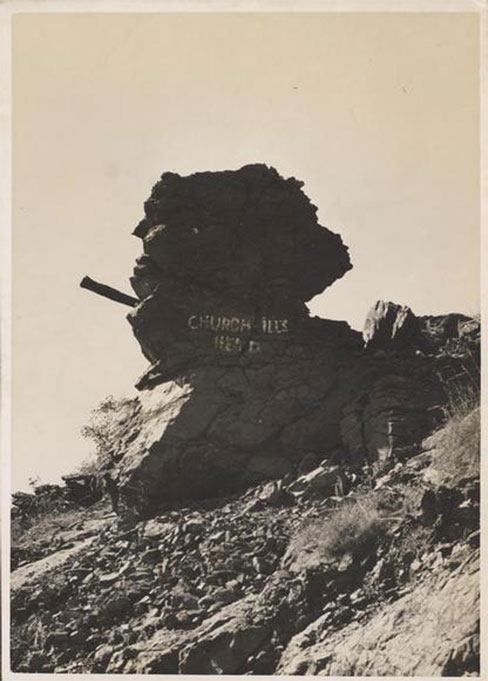

The Army established the Darwin Overland Maintenance Force (DOMF) to transport consignments of military stores and men. With the declaration of war on Japan in December 1941 and the bombing of Darwin in February 1942, the army vehicles of the force carried thousands of tons of supplies and troops along the North-South Road on the four-day journey between Alice Springs and the railhead at Larrimah (Figure 3). By June 1942, an estimated 1,300 vehicles a day were on the road, including American trucking units, overnighting at staging camps at Barrow Creek, Banka Banka, Elliot, and Larrimah.(46) Clement Govett recorded his memories of several trips up and down "the Track" with the Australian Army convoys working on the North-South road during World War II. For Govett and his colleagues, the experience was a mixture of hard grind and long sections of monotonous travelling, punctuated by occasional sightseeing opportunities, which Govett was eager to capture on camera, such as the Devil's Marbles and "Churchill's Head", the latter becoming a well-known and popular landmark among the troops en route to Banka Banka. Govett explained:

Further ahead upon another crest (slight one) was a large rock formation in the shape of a head. Someone had placed a long pole (about five feet) into the "mouth." The rock became known as "Churchill's Head" and the name was painted below. It was a remarkable likeness of Britain's war time PM and was the subject of many hundreds of photographs.(47) (Figure 4 & Figure 5) |

On the final leg to the railhead at Larrimah, the road closely followed the Overland Telegraph Line. Govett was keen to point out a section in which the original single wire was still visible: "This gave all who passed a chance to see the famous telegraph line in its original form...the line that had been built under great hardship many years before...to link Australia with Europe."(48) Govett's memoirs reveal a strong sense of engagement with both the physical environment and the history embodied in the route.

|

Figure 3. Motor convoy approaching staging camp on North South Military Highway 1943. (Negative by Turner. Australian War Memorial. Image ID: 014391.) |

|

Figure 4. Arthur Groom, "Churchill's Head beside the Stuart Highway," ca. 1930-1950. (Arthur Groom Collection, National Library of Australia. PIC PIC 5879/57 LOC Album 1008/2.) |

|

Figure 5. Norma Burns, "Churchill's Head, Stuart Highway," November 1945. (Norma Burns Collection, Northern Territory Library. PH0832/0010.) |

By mid-1942, the road had already begun to disintegrate under the burden of constant heavy military convoys and, in August, it was decided to mobilize state authorities again to rebuild and seal the road. That meant the army convoys had to use detours while construction took place on the main road. These detours were often horror stretches with tree roots and stumps tearing tires; and black soil plains that became heavy slimy clay in the wet or loose bulldust in the dry.(49) Govett described the difficulties of the wet season on the stretch to Larrimah:

On one occasion along this sector very heavy rain fell and the road was washed out for some considerable distance causing long delays. It was necessary to cut mulga trees and lay them across the bitumen and then cover them with wire mesh to form a basis upon which the trucks could crawl along. The road was very badly cut up.(50) |

Bitumen sealing of the North-South Road between Larrimah and Alice Springs was completed in December 1943, and this section of the road was named the Stuart Highway in April 1944 (Figure 6).(51) The southern section of the road between Port Augusta and Alice Springs was less heavily utilized during the war years and so this section was not improved until much later, but by 1968 the southern section was also named the "Stuart Highway." However it was not until the mid-1970s that major upgrading, bituminizing, and some realignment of the route took place. The entire length of the Stuart Highway from Port Augusta to Darwin became part of the National Highway system, introduced in 1974, under which the Federal Government assumed responsibility for funding of major national roads. While the northern section from Alice Springs to Darwin remained relatively close to its original alignment, the southern section between Port Augusta and Alice was rerouted several kilometers to the west of the original line and this new "Stuart Highway" was officially opened in 1987.(52)

|

Figure 6. "Stuart Highway," November 1944, photographer unknown. (Tilson Collection, Northern Territory Library. PH0779/0028.) |

Almost as soon as the northern section of the road was completed during World War II, folklore developed surrounding the Stuart Highway. Nicknamed "The Track," "The Road," "The Bitumen," or, to long distance transport drivers, "the Bitch-O'Mine,"(53) it soon developed legendary status beyond anything its planners or builders could have envisaged. As the sole land transport link between Alice Springs and Darwin, for Territorians the 40-foot strip of bitumen was their life blood, supplying mining districts, pastoral stations; transporting cattle and goods in road trains, sometimes over 100-feet long; and facilitating the tourism boom that began in the post-war era—an essential route for any round and through-Australia "lap." Yet, more than this, as travel writer Kathleen Woodburn wrote in 1947, "The Bitumen is more than just a road. It is an identity, and has a life and influence of its own such as few other highways possess."(54) As has been shown, the Stuart Highway's identity has evolved through a process of interactions between its physical environment traversing the Australian outback, the "dead heart" and tropical north; and the stories associated with the route, particularly that of John McDouall Stuart, the Overland Telegraph, early transcontinental travelers and the World War II construction era. Just as Stuart's successful expedition and the subsequent building of the Overland Telegraph Line were stories of triumph over the harsh environment, so the subsequent building of the highway also represented the further taming of the frontier, the laying of another "path of civilization" through the desert, which resonates with stories of pioneering heroism that have been so fundamental to Australian national foundation myths. Later generations of Australian travelers have sought to engage with those earlier stories, to recapture the romance of a past era, and cast themselves in the role of pioneers as they travel the route, connecting with history, memory, and myth. For example, Douglas Lockwood, who has travelled extensively up and down the Stuart Highway from the mid-20th century, commented that he always stops at Attack Creek, where Stuart abandoned his first journey due to hostile Aborigines, to "drink a silent toast to one of the greatest of all Australian explorers, a man who proved that his heart was made of Highland rock."(55) In 1972, retiree Huldah Turner recorded in her diary of a round-Australia road trip that "Travelling along the Stuart Highway is travelling over Stuart's journey and the trail of the Overland Telegraph."(56)

As the highway's nickname, "The Bitumen" indicates, however, the very nature of the road has changed so that it has become difficult for modern travelers' to identify closely with the hardships of earlier journeys, when contrasted to the relative ease of driving the route since its improvement. For long stretches, especially in the North, it is straight as a gun barrel, running through flat featureless country (Figure 7). Lockwood describes it as "a seemingly endless highway, stretching out between tall mulga into a contracted pencil-line on the horizon, bending gently only once or twice on the first leg to Aileron." He claims that "it becomes a mental struggle to keep the front wheels on the straight-and-narrow."(57) In contrast to the 1927 road guide, the 1994 edition of the Visitor's Guide to Outback South Australia begins its description of the Stuart Highway as follows: "The Stuart Highway from Port Augusta to Darwin lost its reputation as the roughest stretch of road in South Australia when sealing and re-routing was completed in 1987."(58) For some, the lack of adventure on the new road was a disappointment, yet the long, straight stretches of bitumen that now characterize the highway also contribute to its aura and status as one of Australia's iconic road trips, in a similar way to the East-West crossing on the Eyre Highway across the Nullarbor. Sean Condon, while travelling the Stuart Highway in the mid-1990s, experienced a combination of fascination, mind-numbing boredom, and even horror:

I had mistakenly thought all the horror driving was behind us. What a chump. In the Outback (about seven-eighths of the entire country) that sort of driving is never behind you. Australia is too big….Midday. Driving north on the Stuart Highway. Off again into the horror.(59) |

Over time, new journeys overlay new stories onto the road. Australia's vast, isolated interior has long evoked a sense of mystery and menace and these sentiments have been associated with outback roads, including the Stuart Highway, which has witnessed several murders and strange disappearances. The most recent was the bizarre case of the attack on British backpackers, Joanne Lees and Peter Falconio in July 2001 on a stretch of the highway, just over 100 miles north of Alice Springs. Falconio was murdered by another traveler on the road, but a pool of blood beside the road, near where the couple's Kombi van was stopped by the killer, is the only trace of the Englishman ever to be found.(60) This and other outback road trip-turned-nightmare stories have inspired several books and recent Australian horror road genre films such as Wolf Creek, Murder in the Outback, and Road Train.(61) Such representations in popular culture inform subsequent experiences and imaginings of roads like the Stuart Highway.

|

Figure 7. "The Bitumen"—Arrow-straight for much of its length. (Michael Terry, “The Bitumen,” Walkabout 7:1 (1960): 36.) |

With its multiple layers of history, memory, folklore, and myth, built up over time like the dirt, gravel, and bitumen of its physical fabric, being continually reinvented and overlaid by new journeys, how is the Stuart Highway preserved and interpreted? The highway is not listed on any federal or state heritage register. The northern section of the highway, between Alice Springs and Darwin is managed by the Northern Territory Government and Department of Infrastructure and Planning, and from 2007, historic engineering markers were being erected at various locations along the route. According to the Institution of Engineers, Australia, examples of each era of the road's construction remain in use.(62) In 1992 the old North-South road was reopened as a detour from the Stuart Highway and this allowed travelers to experience something of the wartime highway, including the much-photographed and commented-upon natural feature—"Churchill's Head." In 1995, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Victory in the Pacific, a convoy re-enactment "Back to the Track" took place along the old road, and the many veterans who participated re-took photos they had taken and posed for during the war at this landmark.(63)

The 1990s saw the beginning of greater efforts at interpretation to promote the Stuart Highway as part of the Northern Territory's tourism strategy. The Northern Territory Tourism Commission promoted the Stuart as the "Explorer Highway Tourist Drive" with the aim of encouraging travelers to stop at various points along the road. The emphasis was on historic places and stories, with "Info stands" at service stations providing regional maps and historical information.(64) Today, web-based interactive maps provide more detailed and easily accessible interpretation by highlighting particular sections of the route, with brief pop-up windows on towns or sites.(65)

The Northern Territory Tourist Commission's publication, A Wartime Journey: Stuart Highway Heritage Guide,(66) released in 2006, is one of the more innovative and impressive examples of interpretation for cultural tourism. It provides a historical overview of the route as well as section maps with numbered sites and a written description detailing the history of each, together with historic and current photographs. The heritage sites included focus on those associated with Stuart's expedition such as the Attack Creek Memorial,(67) the Overland Telegraph Line, including former telegraph stations and memorials; as well as remnants of the pastoral and mining era. However, the wartime era is most generously represented. The book is accompanied by two audio CDs, with voices, music, and archival sound grabs, telling the wartime story of the highway in the recordings of soldiers, airmen, nurses, and construction workers who describe the wartime sites.(68) Some of the wartime heritage sites include: remains of construction and staging camps, wells, bores, maintenance depots, and old sections of the highway, including Churchill's Head. This goes some way to enhancing travellers' experience of the highway, engaging more fully with history through the use of multi-media.

Yet, there is scope for much more meaningful, integrated, and inclusive interpretive strategies. It is disappointing that the few stories relating to Aboriginal heritage that are interpreted along the route usually focus on sites of conflict with Europeans, such as Attack Creek and the Barrow Creek Telegraph Station. A welcome recent exception to this is the "Stuart Highway Fence" in Alice Springs. The fence, which borders the commercial center of the town, provides a protective screen for the railway yards and incorporates an abstract map of the highway from Port Augusta to Darwin and indigenous art of the region, representing "a cultural mapping of country." Designed to be viewed while moving—either walking, cycling, or driving—the fence is described as "an abstract representation of travel and movement, reflecting the function of the Stuart Highway."(69) Greater use could be made of increasingly sophisticated digital technology that would allow for the telling of multiple stories related to particular sites, and for graphic virtual—including spatial, audio and visual—representations of what it was like to travel the route at different times. Perhaps modern travelers could share their own stories and meanings of traveling the highway at various interpretation centers along the route, thereby adding to the layering of meanings that make up a complex cultural landscape.

The Stuart Highway is a rich cultural resource, but by focusing only on its material attributes or selected stories from specific phases of its development, heritage interpretation strategies miss opportunities for a deeper, richer engagement with the multiple meanings imbued within this enormously significant cultural route. Raymond Williams and Lawrence Levine have defined "culture" as a process: dynamic, not static;(70) "the product of constant interaction between past and present."(71) So "the road" can be seen as a cultural phenomenon, a physical and imagined space reflecting a process of complex interactions between physicality, history, memory, and myth; between the road and its makers, promoters and travelers, being continually overlaid by new journeys and invested with multiple layers of meaning. Such an approach, I believe, can lead to a richer understanding of roads as an integral part of our cultural fabric as well as the culture that produced them.

About the Author

Rosemary Kerr is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Sydney, Australia. She may be contacted at rosemary.kerr@sydney.edu.au.

Notes

1. Keith Willey, "Way of the Never Never," Walkabout 39:11 (1973): 44.

2. The US National Scenic Byways Program, which recognizes roads that are outstanding examples of historic, scenic, recreational, cultural, archeological and/or natural qualities, was established with the first designations of 'All American Roads' and 'National Scenic Byways' in 1996. A biennial conference, Preserving the Historic Road, was founded in America in 1998, bringing together experts from around the world to discuss the latest issues and methodologies in historic road preservation. The conference's co-founder, Paul Daniel Marriott, has also published on the subject—see Paul Daniel Marriott, Saving Historic Roads: Design and Policy Guidelines (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1998), and From Milestones to Mile-Markers: Understanding Historic Roads (Duluth, MN: America's Byways Resource Center, 2004).

3. The concept of "cultural routes" or "cultural itineraries" was refined by UNESCO's World Heritage Committee in 1994 and by the ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) International Scientific Committee on Cultural Routes (CIIC), established in 1998. A cultural route or itinerary represents spatial links between societies based on population movements, encounters, exchange, and dialogue across countries or regions, where the meaning of the whole route is greater than the sum of its parts, a prime example being the Silk Road. CIIC website online at: http://www.icomos-ciic.org/index_ingl.htm

4. Australia ICOMOS has organized two major conferences on the subject of cultural routes ("Making Tracks: From Point to Pathway: the Heritage of Routes and Journeys," Alice Springs, May 2001) and historic roads ("Corrugations: The Romance and Reality of Historic Roads," Melbourne, November 2005). Select papers from both conferences have been published in special issues of Historic Environment 16:2 (2002) and 20:1 (2007). However, apart from the listing of the convict-era Great North Road on the World Heritage List and the recent nomination of the Great Ocean Road to the National Heritage List, relatively little work has been done on the identification, assessment, and management of historic roads and routes at the state and national level in Australia.

5. As well as the works cited, several other studies have explored "the road" as a cultural phenomenon and its place in American consciousness, for example: Ronald Primeau, Romance of the Road: The Literature of the American Highway (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1996); Kris Lackey, Road Frames: The American Highway Narrative (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1997); Phil Patton, Open Road: A Celebration of the American Highway (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1986); Thomas Schlereth, Reading the Road: U.S. 40 and the American Landscape (Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Historical Society, 1997); and John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, Motoring: The Highway Experience in America (Athens, GA & London, UK: University of Georgia Press, 2008).

6. Karl Raitz, ed., The National Road (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), xi, 44, 103, 119, 121.

7. Reverend Frank G. Brainard, preaching in Salt Lake City, Utah on October 19, 1913, cited in Drake Hokanson, The Lincoln Highway, Main Street Across America (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1988), 14.

8. Marguerite S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880–1940 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute Press, 2001), 136-137.

9. Hokanson, The Lincoln Highway, xv.

10. Peter B. Dedek, Hip to the Trip: A Cultural History of Route 66 (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2007), 2-8.

11. Described as the longest highway in the world within the one national boundary, Australia's Highway 1, was an amalgam of existing roads, joined together and improved as part of a national roads system begun in the mid-1950s and formalized in the 1970s.

12. George Farwell, Around Australia on Highway 1 (Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, Adelaide, AU: Rigby Limited, 1978).

13. Val Donovan and Colleen Wall, eds., Making Connections: A Journey along Central Australian Aboriginal Trading Routes (Brisbane, AU: Arts Queensland, 2004), 41.

14. T. G. H. Strehlow, "Culture, Social Structure, and Environment in Aboriginal Central Australia," in Aboriginal Man in Australia, ed. Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H. Berndt (Sydney, AU: Angus & Robertson, 1965), 134-135.

15. Donovan and Wall, Making Connections, 40.

16. Colin Harris, "Culture and Geography: South Australia's Mound Springs as Trade and Communication Routes," Historic Environment 16:2 (2002): 8.

17. Donovan and Wall, Making Connections, 54.

18. While Burke and Wills had reached the Gulf of Carpentaria from Melbourne in February 1861, they perished on the return journey. Stuart first made an attempt to cross Australia from south to north in 1860 but was forced to turn back after reaching a point just beyond Tennant Creek due to lack of water and provisions, illness, and threatened attacks by Aborigines. J. L. Betheras, "The Story of John MacDouall Stuart," Walkabout 23:12 (1957): 29.

19. Other explorers such as Charles Sturt, Benjamin Babbage, and Peter Warburton had also made attempts to reach the center of the continent.

20. William Hardman, ed., The Journals of John McDouall Stuart during the Years 1858, 1859, 1860, 1861 & 1862, When he Fixed the Centre of the Continent and Successfully Crossed it from Sea to Sea (Facsimile edition, Adelaide, AU: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1975) originally published London, UK: Saunders, Otley & Co., 1865, 343.

21. Harris, "Culture and Geography," 9.

22. Hardman, Journals of John McDouall Stuart, 406-407.

23. See Russel Ward, The Australian Legend (Oxford, Melbourne, AU: University Press, 1958) and J. B. Hirst, "The Pioneer Legend," Historical Studies 18:71 (1978): 316-337.

24. John Mack Faragher, Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner: "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" and Other Essays (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998).

25. Betheras, "The Story of John McDouall Stuart," 32-33.

26. Howard Pearce and Bob Alford, A Wartime Journey: Stuart Highway Heritage Guide (Darwin, AU: Northern Territory Tourist Commission, Dept. of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts, NT Archives Service, 2006), 90.

27. Frank Clune, Roaming Around Australia (Melbourne, AU: Hawthorn Press, 1947), 193.

28. Jerome J. Murif, From Ocean to Ocean, Across a Continent on a Bicycle, An Account of a Solitary Ride from Adelaide to Port Darwin (Melbourne, AU: George Robertson & Co., 1897), 12.

29. The Great Northern Railway was constructed between 1879 and 1891 from Port Augusta and Oodnadatta. Meanwhile, in 1886 construction began on the northern section of the line from Darwin to Pine Creek. Plans for rerouting and extending the railway between Adelaide and Darwin began in 1924 and, by 1929, the line reached Alice Springs. This section became the famous Ghan'Railway, named because of the Afghan cameleers who had plied the route carrying supplies and wares to pastoral and mining settlements along the route since the 1860s. Also in 1924 the northern section was extended as far as Birdum, about 320 miles south of Darwin, still leaving a gap of over 600 miles between Birdum and Alice Springs. The entire rail link was not completed until 2003. See Douglas Wells, From Wagon Tracks to Bitumen: The Evolution of the Stuart Highway (Hathorndene, SA, AU: Douglas Wells, 2005); and Basil Fuller, The Ghan: The Story of the Alice Springs Railway (Sydney, AU: New Holland Publishers Australia Pty. Ltd., 2003).

30. Murif, From Ocean to Ocean, 84-85.

31. The symbolic significance of a transcontinental crossing was often marked by bathing in the sea at the start and end points of the journey. Transcontinental motor tourists crossing the United States, usually from east to west, also ritually dipped their tires in the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific to mark the start and finish of their journeys, symbolizing their embrace of the nation. See Hokanson, The Lincoln Highway, xv; and H. C. Allen, Bush and Backwoods, A Comparison of the Frontier in Australia and the United States (Sydney, AU: Angus & Robertson, 1959), 122.

32. Murif, From Ocean to Ocean, 191.

33. Australian Motorist 1:1 (1908): 17. Dutton and Aunger initially attempted the crossing in 1907 but were forced to abandon their car, an eight horsepower Talbot, named "Angelina," due to mechanical failure. On this journey, they encountered intrepid Australian adventurer, Francis Birtles, cycling in the opposite direction from Darwin to Adelaide.

34. H. Murray Aunger's account of the journeys in Fred Blakeley, Hard Liberty, A Record of Experience (London, UK: George G. Harrap & Company Ltd., 1938), 161, 162.

35. Australian Motorist 1:1, (1908): 17.

36. Australian Motorist 1:1, (1908): 19.

37. Bell and her daughter traveled around the perimeter of Australia from Perth to Darwin, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and returned to Perth in 1925-1925; Sandford and Christie's route was Sydney – Adelaide – Perth – Adelaide – Darwin – Adelaide – Sydney in 1927; Robertson and Howell also completed the Adelaide to Darwin route among many other long-distance motor trips in the late 1920s.

38. See Margriet Bonnin, "A Study of Australian Descriptive Travel Writing, 1929-1945" (Ph.D. diss., University of Queensland [Australia], 1980); Timothy John Fetherstonhaugh, "The Journal, Walkabout and Outback Australia 1930s-1950s: A Romantic Rapprochement with the Landscape in the Face of Modernity," (Ph.D. diss., Murdoch University [Australia], 2002); Richard Waterhouse, The Vision Splendid, A Social and Cultural History of Rural Australia (Fremantle, AU: Curtin University Books, 2005).

39. Georgine Clarsen, Eat My Dust: Early Women Motorists (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 120-139.

40. The Tourists' Road Guide for South Australia (Adelaide, AU: W. K. Thomas & Co., 1927), 2.

41. The Tourists' Road Guide, 96.

42. Michael Terry, "The New Road Link with Darwin," The Australasian Engineer 41:297 (1941): 13.

43. Alex Tanner, The Long Road North (Richmond SA, AU: Alex Tanner, 1995), 1-2, 15; D. L. Bernstein, "Building 'the Bitumen,'" Walkabout 32: 9 (1966): 28-31, 28.

44. Terry, "New Road Link," 13.

45. Terry, "New Road Link," 13.

46. Pearce and Alford, A Wartime Journey, 33.

47. Clement N. Govett, "Along the Track—The Stuart Highway, Northern Territory," (Manuscript compiled at Brisbane, Qld, May 1974) in Clement N. Govett–Further Papers Concerning the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces, [MLMSS 2515/1: Microfilm Reel CY 775, frames 84-151.]: 117.

48. Govett, "Along the Track," 122.

49. Pearce and Alford, A Wartime Journey, 33.

50. Govett, "Along the Track," 122.

51. Tanner, The Long Road North, 153-154, 204.

52. Wells, From Wagon Tracks to Bitumen, 140-141.

53. Douglas Lockwood, Up the Track (Adelaide, AU: Rigby Limited, 1964), 13.

54. M. Kathleen Woodburn, "The Bitumen," Walkabout 13:5 (1947): 16-20, 16.

55. Douglas Lockwood, "The Years Since Stuart," Walkabout 26:4 (1960): 17.

56. Hulda M. Turner, "A Round-Australia Journal 30 weeks and 25,000 miles in 1972," in Hulda Turner Papers, 1940-2003, [MLMSS 7520]: 98.

57. Lockwood, Up the Track, 54-55.

58. Visitor's guide to Outback South Australia Featuring the Stuart Highway, Oodnadatta Track, Strzelecki Track, Birdsville Track, Desert parks and More (Adelaide, AU: Outback Tourism South Australia, 1993-94), 5.

59. Sean Condon, Sean & David's Long Drive (Melbourne, AU: Lonely Planet Publications, 1996), 94-95.

60. Lees and Falconio were traveling around Australia as part of a world backpacking adventure. Driving north on the Stuart Highway at night, heading from Alice Springs to Darwin, their Kombi van was stopped by the driver of a white four-wheel drive utility vehicle, which had been following the couple for some time. The driver told Peter Falconio that he could see smoke coming from the Kombi's exhaust. When Falconio went with the man to investigate, Lees heard a gun shot. The gunman then assaulted her, bound her hands, and threw her into the back of his vehicle. She somehow managed to escape, hiding among the mulga and spinifex scrub for hours while the gunman and his dog searched for her, amazingly, without success. When the killer gave up his search, Lees flagged down a passing road train, whose drivers took her to Barrow Creek, about 280 kilometers north of Alice Springs, where they raised the alarm with police. So began one of the most bizarre criminal investigations in Australia's history. Doubts over Joanne Lees' improbable story, failure to find any trace of the alleged gunman, his four-wheel drive, or Falconio's body, dragged on for years before Bradley John Murdoch, a mechanic then living in Broome, Western Australia, was finally convicted of the assault and murder in December 2005.

61. Greg McLean, Wolf Creek (2005) (this film also draws on the 1990s backpacker serial murders on the Hume Highway in south-eastern Australia); Tony Tilse, Murder in the Outback (2007) is a dramatized telemovie based on the Joanne Lees story; Dean Francis, Road Train (2010).

62. Historic Engineering marker, Stuart Highway North, Institution of Engineers, Australia & Department of Planning and Infrastructure, 2007. Engineers Australia website, online at: www.engineersaustralia.org.au/, accessed in June 2010.

63. Pearce and Alford, A Wartime Journey, 55; Annie Bonney, "Victory in the Pacific: Fiftieth Anniversary Commemorations in the Northern Territory," Research Paper (Darwin, AU: Northern Territory Library, 1995).

64. David Carment, A Past Displayed: Public History, Public Memory and Cultural Resource Management in Australia's Northern Territory (Darwin, AU: Northern Territory University, 2001), 91.

65. For example: Tourism Information Distributors Australia website, online at: http://www.exploringaustralia.com.au/stuart.php

66. Published in association with the Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts and the Northern Territory Archives Service.

67. Attack Creek was the site at which Stuart abandoned his first attempt at a complete south-north crossing of the continent in 1860 due to the presence of hostile Aborigines. Disappointingly, the few stories relating to Aboriginal heritage that are interpreted along the route usually focus on sites of conflict with Europeans.

68. Pearce and Alford, A Wartime Journey, Introduction.

69. "Stuart Highway Fence" by Susan Dugdale & Associates, online at: http://www.architecture.com.au/awards_search?option=showaward&entryno=2009001756

70. Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London, UK: Croom Helm, 1984), 90, cited in Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788 (South Melbourne, AU: Longman Australia, 1995), ix.

71. Lawrence Levine, Highbrow, Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 33.