Article

Improving Archeological Predictive Modeling for the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area

by J. Brett Hill, Mathew Devitt, and Marina Drigo(1)

Predictive models are among the most attractive and useful strategies for cultural resource managers attempting to estimate unknown archeological site locations. Using inferences from known archeological sites and their environmental context to predict unknown site locations and to model archeological sensitivity has become increasingly practical, and technical refinements in model development now make it relatively easy to produce such models.(2) Yet, several methodological and theoretical dilemmas have inhibited the full realization of predictive modeling potential in the management context. We propose an approach that offers both improved model efficiency and more effective use of data to address contemporary challenges. These improvements are both technical and conceptual, and focus on the ways existing archeological and geographic data sets can be more clearly related to our questions.

At the technical level, identifying and deriving variables that structured human land use are some of the most important and problematic aspects of predictive models.(3) We know that many environmental attributes such as water availability and terrain were critical, and abundant digital data on these are readily available. Many scholars have made valuable progress on techniques for deriving useful indices from these data.(4) However, significant differences between current and past conditions, as well as scalar discrepancies between current mapping standards and past land use, hinder model development.

At the conceptual level, archeologists commonly acknowledge the importance of predictive modeling for CRM,(5) but most of the method and theory behind modeling is dominated by an academic goal of explaining past human behavior. Relatively little attention has been given to ways of integrating such research goals with other non-academic interests in the archeological record. Furthermore, while some acknowledge the differences between CRM and academic research goals, relatively few pay attention to variability within the CRM context.

We found ourselves at odds with some attitudes toward predictive modeling that affected our goals and methodological choices in ways we think merit greater discussion. Our goals in this paper are twofold, to: 1) illustrate a simple but useful technique for modeling the importance of water in an arid environment, and 2) address some of the theoretical and practical implications of the varying goals of predictive modeling.(6)

Archeological Sensitivity in the National Heritage Area

In recent years, the government of Pima County, Arizona, and other organizations have developed the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan (SDCP), including a Geographic Information System (GIS) for use in planning development in the context of rapidly increasing local population. Among the many components of this system is an archeological sensitivity map of the eastern part of the county, where most development is occurring. This map was produced through a collaboration between archeologists and planners. First, a team of knowledgeable local archeologists manually drew maps of areas they knew to have high concentrations of archeological sites. Planners then integrated this information with other information in the GIS to enable the county government to evaluate spatial relationships among cultural resources and other aspects of the environment affecting policy and planning.

A recent initiative to establish a National Heritage Area (NHA) in the Santa Cruz Valley prompted a renewed interest in the SDCP archeological sensitivity map and a desire to produce something comparable for Santa Cruz County. Eastern Pima County comprises the lower (northern) portion of the Santa Cruz Valley as conceived for the NHA, and Santa Cruz County comprises the upper (southern) portion of the valley. Unlike Pima County, Santa Cruz County did not have an archeological sensitivity map. The NHA feasibility study, however, required thematic maps of the entire area as a single management entity. Given budgetary and time constraints, we were required to use existing data and available tools to produce such a map. Based on information acquired from public sources including the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the Arizona State Land Department (ASLD), and the AZSITE (Arizona's archaeological sites database,) and using ArcGIS, and SYSTAT software, we developed a predictive model of archeological sensitivity.

An important aspect of this project was the need to produce maps of resources relevant to the specific goals of developing the NHA. Furthermore, these maps needed to provide a sense of the resources as they were integrated into a set of ten interpretive themes focusing on the natural and cultural history of the area. Of these ten, Native American Lifeways (11,000 BC to Present) and Desert Farming (2000 BC to Present) are directly related to our modeling and are focused on settlement and land use prior to European contact. Most of the themes also emphasize various aspects of life along the river oases that are so prominent in this desert environment and provide the unifying principle for the NHA. A key focus of our analysis was demonstrating in a clear and concise way the archeological aspects of this relationship between land use and the Santa Cruz River system.

The larger goal of the NHA designation is to develop heritage and nature tourism in the area. Estimated impacts of increased tourism resulting from the NHA designation are approximately $1.8 billion and 40,000 new jobs over the first ten years. Given that this development is focused in large part on the cultural resources of the area, it is necessary to both illustrate where those resources are located and how they will be affected by increased activity. Achievement of this goal is limited by the still unknown elements of the archeological record.

A good deal is currently known about cultural resources in the area but more remains to be discovered and incorporated into our understanding of the region's past. For example, the importance of this area in the early development of agriculture and sedentary life in North America remained unknown until recent highway salvage work revealed deeply buried deposits in the river floodplain dating earlier than 4000 B.P.(7) Thus we desired a model, reflecting potential for archeological materials and their relationship to the environmental factors structuring other heritage tourism themes, which would illustrate the unique and significant contribution of the Santa Cruz Valley to American heritage.

The Santa Cruz Valley in Santa Cruz County

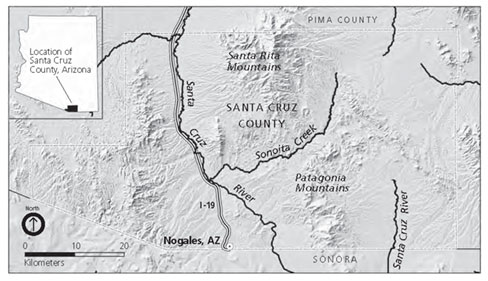

Santa Cruz County is located in southeastern Arizona adjacent to the United States-Mexico border. (Figure 1) It comprises an area of approximately 3200 km2 of Basin and Range topography with elevation ranging from 900 to 2880 meters above mean sea level. The dominant geographic feature in the region is the Santa Cruz River, which begins in Arizona, flows into Sonora, Mexico, and then curves west and north to re-enter Arizona and flow toward its confluence with the Gila River in south-central Arizona. The Santa Rita and Patagonia Mountains flank the river valley and contribute a large portion of its flow. The region is dominated by Sonoran and Chihuahuan Desert vegetation, except in the mountain elevations where Madrean evergreen woodland contains relict Pleistocene flora and fauna typical of cooler and wetter climates.(8) Annual precipitation in the area ranges from 300 mm in the low desert to 900 mm in the higher elevations.

|

Figure 1. Location of Santa Cruz County in southeastern Arizona. |

Culturally the area has been the location of human habitation since the early stages of New World occupation over 12,000 years ago, and several Paleo-Indian sites are recorded here. It is also the location of Archaic and Early Agricultural Period sites, and an ideal riverine setting for the introduction of domesticates to the region approximately 3,500 to 4,000 years ago.(9) During the last centuries before European contact, what is now Santa Cruz County was on the border between the Hohokam and Trincheras culture areas. When the first European explorers arrived, O'odham groups, whose descendents still live here, occupied the area. Overall there is good evidence that some parts of the area were occupied fairly consistently for several thousand years, and many areas of occupation in earlier times are still the primary loci of occupation today.

Practical and Theoretical Implications of Prediction

Essential questions in predictive modeling concern both what is being predicted and the purpose of the prediction. Modelers typically emphasize the ability of archeologists to accurately predict and ultimately explain patterns in the archeological record.(10) Such a view undervalues the role of predictive modeling in understanding the relationship between past and future land use, which is a vital objective in many CRM contexts. In these situations, prediction takes on a more dynamic role. In our project in Santa Cruz County we found that shifting our perspective had significant implications for the way we developed our model.

A central debate in different approaches to predictive modeling concerns the role of explanation. Most argue that explanation is the primary goal of prediction and that efforts toward predictive models without explanation are misplaced.(11) Simple prediction is perceived as a vacuous mathematical exercise in the absence of a higher purpose that justifies the expense of public funds. As Timothy Kohler and Sandra Parker note, "Sites are not worthwhile ends in themselves, but the understanding of human behavior and development that can be extracted from them is."(12)

Current historic preservation laws and regulations emphasize the importance of information potential and most CRM work is developed with an explanatory research design. The importance of information potential in CRM is supported in concept and by its prevalent use as the criterion for designating sites eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in the United States.(13) This emphasis on information and understanding is evident in most academic and CRM work and constitutes a valid goal. However, the determination of significance based on information potential has recently received more careful scrutiny(14) and there is increasing awareness that traditional scientific notions of information to be gained from excavation do not adequately encompass the range of values inherent in archeological landscapes.

There are multiple valid interests in the archeological record. William Lipe proposed that cultural resources have four different kinds of value including informational (research), economic (market value), aesthetic (contemporary appeal), and associative (sentimental or familiar).(15) He notes that management of resources will involve competition among interest groups emphasizing different values.

Martin Carver argued that ultimately all other values of the archeological record are derived from research informing us about what is important or relevant.(16) Following a more diverse appreciation of importance and relevance, we argue that this perspective is too narrowly shaped by a perspective that fails to accommodate the wide variety of reasons people have valued remains of the past for millennia.(17)

This problem is not simply one of contemporary multiculturalism but has historical salience within a Western tradition as well.(18) Carver acknowledged that even within a research context the importance of the archeological record is a fluid matter, dependent on current conditions and "in a state of continual redefinition."(19) This flux results from social and theoretical concerns that are constantly changing, emphasizing the still unknown aspects of the archeological record, and the ever-changing interface between that record and equally unknown future research values. We agree, but emphasize that the interface with the past is not limited to future research values.

Many people have a strong interest in the archeological record that may diverge substantially from the goal of scientific explanation, and their primary reason for wanting to protect ancient sites is not necessarily to save them for future information gathering.(20) While such conflicts of interest are often perceived to stem from fundamentally different worldviews, similar divergences occur within the Euro-American historic preservation community. To take a simple example from our region, saving the last Hohokam ballcourt from destruction might be of debatable scientific value, yet few archeologists would dispute the merit of such a plan. A full discussion of the diverging interests and understandings of the past is beyond our scope but is the subject of considerable recent publication.(21)

The concept of heritage is a central issue, both in the practice of CRM and in our project to support the development of a National Heritage Area. The term heritage refers to inheritance or tradition, and suggests both the process of passing on meaning through time and of negotiating present meaning.(22) The various parties cooperating to promote the heritage of the Santa Cruz Valley represent a broad range of interpretation about its meaning. Certainly the scientific meaning of archeological materials in the region is valid, but so are the multitude of meanings for diverse communities tracing their ancestry through this region, and the diverse communities living with the rapid environmental and economic changes present and forecast. Perhaps sites are not worthwhile ends in themselves, but to the degree that they are meaningful in the heritage process of diverse groups, their value must transcend the understanding of human behavior and development that scientists can extract from them. Consideration of alternative ends emphasizes the value of alternative approaches to methodological issues.(23)

A growing sense of the economic, landscape, and political values of the archeological record alters the role of prediction in a number of important ways.(24) Modeling in this context requires maps focusing on landscapes and deposits instead of sites, attention to formation processes that affect the future of resources, and the potential for rapid, large-scale iterative model development using readily available tools and data. In addition, modeling for alternative needs may affect issues such as sample selection and quantitative approaches. These requirements are not irrelevant to academic research, but the CRM context makes their practical solution a more urgent concern and may alter the cost/benefit of striving for a tenuous and problematic explanation whose value is likely temporary. Improved predictive success can be achieved through strategies that do not necessarily improve our scientific understanding of past cultures. In fact, such understanding may be tangential to primary goals of preservation and conservation.

As part of a broader effort, the model described here must clearly convey the richness of our record of the past and a sense of how that record is integrated with other resources. These messages would not be well served by a treatise on the subtleties of site function or the complex processes involved in decision making by ancient peoples. Rather, the desired product is one with which archeologists are able to accurately illustrate our current understanding of places of importance in the region's human history. This product will then be integrated with complementary efforts by ethnographers and historians, natural scientists representing ecological interests, and current land and business owners in the area. This combination of views is necessary to fill out our understanding of the landscape and its value. We must then communicate our results effectively to a wide audience, including policy makers and the public.

To effectively accomplish these goals we must be applied anthropologists, fully engaged with the community and mindful of our work in a larger context.(25) One of our major challenges in this type of work is to identify sensitive locations, or those parts of the archeological record facing imminent threat of conflict with other dynamic elements in the community. Furthermore, the model we develop must be recognized as a single step in an evolving process for which many future models will be required to address the constantly changing nature of the present as articulation of past and future.

Ancient Data and Future Probability

Archeologists describe several techniques to develop models using GIS and statistical software. The dominant form of model is one that assesses the correlation among archeological site locations and qualities of the natural environment. One popular and robust statistical technique is logistic regression,(26) which has proven to be a powerful and easily interpreted method when appropriate data are available.(27) Correlation statistics such as these require known archeological and geographic input in order to estimate unknown matters of interest such as the likelihood of an activity impacting the archeological record.

Environmental Data

Obtaining and developing useful environmental data can be the most time consuming and costly aspect of a predictive modeling project. While some projects are able to include collection of environmental data in conjunction with archeological survey, our project constraints did not allow for such an integrated approach. Rather, we used available data that was typically collected for quite different purposes and recorded at a scale that may be inappropriate for use in modeling some aspects of prehistoric land use.(28) However, we needed to derive meaningful attributes from these data and still discriminate useful variation among geographic attributes. Because our study is at a regional scale, we believe that broad environmental characteristics such as soil, climate, and vegetation structured settlement choices.

The primary sources of digital environmental data for this region are the Arizona Land Resource Information System (ALRIS), and the United States Geological Survey (USGS), both of which provide free data for use in non-commercial applications. Slope and flow accumulation data were derived in ArcGIS from the digital elevation model (DEM) using the Spatial Analysis extension and the ArcHydro data model.(29)

One especially important consideration in site location that is difficult to address with standard hydrography data is the availability of water. In the desert southwest, this has always been an important consideration for settlers, and it is a particularly troublesome thing to identify with current data in a way that reflects actual availability over thousands of years. Standard hydrography data available from sources such as the USGS do not adequately indicate the subtle variation in water availability in the desert and do not address differences between current conditions and those in the past. Simple distinctions between perennial and ephemeral streams, or methods of identifying stream order do little to indicate the actual quantity and timing of water availability that are critical to human uses. Furthermore, a great deal of change in surface water availability has occurred over time, particularly in the last century as modern uses have affected flow characteristics and the water table.

In the present analysis, for example, only two small segments of the many streams in the area were identified as perennial, the rest considered ephemeral. The historical literature documents a much more extensive perennial flow in the larger streams of this region.(30) In addition, the mean distance to any stream from sites used in these analyses was 294 m, compared to 303 m for non-site locations. This three percent difference in distance to ephemeral water sources hardly reflects its importance in this desert region and is minimally useful in discriminating among likely settlement locations. To best identify hydrologically useful locations would require a laborious paleoenvironmental study emphasizing geomorphological evidence of past fluvial conditions. In the absence of such detailed study, we focused on hydrological modeling as the best way to understand the relative availability of water to ancient settlers.

Hydrological modeling characterizes the direction and accumulation of water flow based on terrain. The size of watershed is one of the most important qualities affecting the amount of water that flows in a given drainage. It is possible to calculate the accumulated surface flow available at any location based on slope and aspect values provided by digital terrain data. We used a neighborhood sum(31) to indicate the total area of watershed contributing to hydrologic flow within 1 km of a site location. This measure characterizes the amount of flow available in close proximity to a settlement and reflects variable availability as the distance from sites to drainages increases. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of locations at stream confluences that have been noted as persistent places.(32) Stream confluences both increase the area of high flow potential within such a radius and reflect the importance of tributaries in raising water table levels and creating more regular flow.(33) Calculation of the neighborhood statistic resulted in a mean flow accumulation in the vicinity of sites that is more than 127 times greater than the mean for non-site locations, and appears far more indicative of the variable availability of water in the desert. Development of this variable offers both a substantial gain in the efficiency of our model and a clear reflection of the importance of water in this environment.

Archeological Data

Arizona State Museum (ASM) and AZSITE provided information on site locations and survey projects in Santa Cruz County. We focused on pre-European contact period sites because a separate effort was under way to identify historic properties and it was unnecessary and probably inadvisable to model their locations.(34) We narrowed our scope to habitation sites because these are likely to represent the broadest range of activities relevant to the stated interpretive themes, and they freed us from the difficulty of identifying tenuous site functions. We identified a set of 160 pre-contact, habitation sites deemed to be most representative of past land use and of cultural resources needing protection.

The use of these archeological survey data in a statistical model poses problems of analysis because they are biased and do not represent a random sample. Because this problem is common for researchers attempting to use existing data, archeologists have explored ways to compensate for such bias.(35) A random sample is important to provide a representative set of locations for statistical analysis. For many purposes it would be desirable to have a sample of locations representative of the full range of past land use. The use of unrepresentative data in model development risks missing important and unknown aspects of behavior.(36) Jeffrey H. Altschul argued that it is precisely these unknown elements that are most important because they provide the most new information.(37)

It is helpful, however, to consider more closely the questions of bias and representativeness. The importance of a representative sample rests on an assumption that it is representative of something we want to explain. In a scientific context, past settlement and land use are typically what we want to explain. If, however, our goal is to model the articulation of past land use with current and future land use, the existing sample bias may be viewed as a useful measure of the interface between the archeological record and recent land use. While not a random sample, it is very representative of recent and contemporary interest in the landscape from a development point of view. That is, the region's distribution of known sites and modern archeological surveys is a good reflection of the range of land use it has received over the last several decades. The variable scrutiny received by different areas is an indication of how much activity has occurred and is likely to occur in the near future.

The goal of producing a sensitivity map suggests a desire to identify cultural resources that are subject to imminent effect by development, and modeling sensitivity requires consideration of both the resources and development trends. Bias inherent in much existing archeological data produced by CRM may essentially be considered a weighting factor for threat level. Rather than apply techniques to correct for this bias, we chose to use it strategically, emphasizing those areas most likely to be impacted by developments in the near future.

Results and Discussion

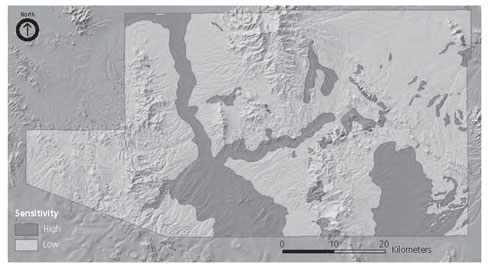

A combination of variables including: flow accumulation, elevation, distance to springs, soils, and vegetation produced the best results. Our model produced mean probability estimates for site locations of .97 and for non-site locations of .03, indicating strong discrimination between location types. Figure 2 depicts a resulting archeological sensitivity map reflecting a 76 percent gain in efficiency by focusing attention on only 21.4 percent of the total area for likely impacts.(38)

|

Figure 2. Archeological sensitivity map resulting from more efficient process. |

The model accurately characterizes the importance of the Santa Cruz River Valley where most land use, both ancient and modern, seems to be concentrated. For example, the emphasis apparent particularly in the upper reaches of the Santa Cruz Valley corresponds well with findings of other researchers documenting biodiversity and other indices of natural resource wealth.(39) This emphasis in the model is driven by recent focus on this area and illustrates the connections between current interest and archeological sensitivity.

Despite our current need to settle on a particular model illustrating this articulation, it is essential to consider modeling as an ongoing, iterative process. Ultimately, more detailed management plans may require more elaborate modeling efforts and consideration of new variables as we strive to clarify our understanding of more particular problems and relationships. In addition, our understanding of the archeology of this region is certain to improve dramatically as more research is conducted in coming years. Development is certain to expand greatly in the area, changing the articulation of past and present interests. The present model cannot be considered a final word on archeological sensitivity in Santa Cruz County. Rather we hope that our efforts and the lessons learned will serve as a productive foundation for continued work. We are encouraged that this initial project has offered a useful model and numerous valuable insights into the modeling process.

Finding the Fit Between Questions and Data

Predictive modeling has long held promise as a powerful tool to help archeologists understand patterns of land use. Technological improvements in methodology, computing power, and data access now make useful modeling a practical goal for many in our field. In the project described here we were able to use readily available data and technology to produce a model offering significant insight into the ways in which the landscape of southeastern Arizona articulates past and contemporary land use. We are able to produce a map depicting those areas in Santa Cruz County most susceptible to the conflicting goals of preserving and highlighting our unique past, and future economic development. Our map explicitly focuses on areas of archeological value that are likely to be both a significant factor shaping development efforts and significantly affected by those efforts.

For this we are indebted to a generation of archeologists who have developed techniques and raised important questions about predictive modeling. At the same time, we encountered new challenges and solutions to problems many in our field may find useful. We hope the present discussion offers some value in two areas of predictive modeling in archeology.

First, the matter of water availability is a critical factor in many parts of the world and tools for hydrological modeling in GIS offer valuable methods for more accurately assessing the variable availability of water across a landscape. We successfully used a fairly simple approach quantifying accumulated flow with good success. This approach can be improved in the future with more complex modeling of variable precipitation and geology in different drainages that also affect the amount of available surface water.

Second, the matter of archeological data for model development is problematic particularly for small projects with limiting financial and schedule constraints. In many areas, abundant archeological data may be available that has been perceived as unsuitably biased for modeling purposes. While others offer useful suggestions for addressing bias in archeological data, we argue that in some CRM contexts this bias may be turned to advantage as a weighting factor emphasizing contemporary threats to cultural resources. The bias in existing data thus offers a useful measure of threat sensitivity that is important in managing and preserving these resources. This bias focuses our attention on the future of the archeological record as much as its past.

In preservation archeology, the goal of predictive modeling is no longer simply explaining past behavior but how that behavior influences the present and takes on contemporary economic, political, and ideological values. Substantial amounts of money and effort are currently devoted to the preservation and recognition of cultural resources in the United States and many other countries. If this trend is any indication of value as perceived by society, then diverse approaches to predictive modeling that offer efficient and timely maps of past land use become important elements in our view of the historical landscape. The current project was initiated as part of a larger heritage tourism and preservation effort and requires a focus on the ways that past land use are integrated with current land use, and to an increasing degree will structure future land use. It is, in fact, the express purpose of this effort to create a model of the landscape as a product of the past to structure the future. This is not a model of the past to simply inform us, but an active effort to shape the future in a particular way.

Archeologists are not simply in the business of explaining why people did what they did in the past, and we do not here pretend to offer new knowledge on this subject. Instead we argue that part of our job as archeologists is to inform a public interested in balancing preservation and development about where these goals interact and conflict with one another. To answer "What are we learning that we didn't already know?" we do not simply need to explain the past better, but rather to explain where the past will impact, and be impacted by, a future we predict will still care.

About the Authors

J. Brett Hill is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology/Anthropology, Hendrix College, Conway, AR 72032. He may be contacted at hillb@hendrix.edu. Phone: (501) 450-3828 Fax: (501) 450-1400.

Mathew Devitt is a Preservation Archaeologist with the Center for Desert Archaeology, 300 North Ash Alley, Tucson, AZ 85701. He may be contacted at mdevitt@cdarc.org.

Marina Drigo is a Research Modeler with the PERTAN Group, 44 East Main Street, Suite 403, Champaign, IL 61820. She may be contacted at marina.drigo@pertan.com.

Notes

1. We would like to thank the Center for Desert Archaeology and William H. Doelle for the support necessary to conduct this research, and to pursue the establishment of the Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area. We also thank the following people for their thoughtful comments on the ideas presented in this paper: Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Jeffery J. Clark, Patrick D. Lyons, Anna A. Neuzil, and Linda J. Pierce. Miller McPherson also provided advice on statistics and Barbara Little provided editorial advice. ArcGIS and the Spatial Analysis extension were provided through a grant from the ESRI Conservation Program. Any errors of fact or interpretation remain entirely the authors' responsibility.

2. See for example chapters in Konnie L. Westcott and R. Joe Brandon, eds., Practical Applications of GIS for Archaeologists: A Predictive Modeling Toolkit (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2000).

3. James I. Ebert, "The State of the Art in 'Inductive' Predictive Modeling: Seven Big Mistakes (and Lots of Smaller Ones)," in Practical Applications of GIS for Archaeologists: A Predictive Modeling Toolkit, ed. Konnie L. Westcott and R. Joe Brandon (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2000), 129-134.

4. Kenneth L. Kvamme, "Determining Empirical Relationships Between the Natural Environment and Prehistoric Site Locations: A Hunter Gatherer Example," in For Concordance in Archaeological Analysis: Bridging Structure, Quantitative Technique and Theory, ed. Christopher Carr (Prospect Heights,IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 1985), 208-238. Robert E. Warren, "Predictive Modelling in Archaeology: A Primer," in Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology, ed. Kathleen M. S. Allen, Stanton W. Green, and Ezra B. W. Zubrow (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1990), 90-111. Richard B. Duncan and Kristen A. Beckman, "The Application of GIS Predictive Site Location Models Within Pennsylvania and West Virginia," in Practical Applications of GIS for Archaeologists: A Predictive Modeling Toolkit, ed. Konnie L. Westcott and R. Joe Brandon (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2000), 33-58.

5. Lynne Sebastian and W. James Judge, eds., Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1988).

6. J.Brett Hill, Mathew Devitt, and Marina Sergeyeva, "Predictive Modeling and Cultural Resource Preservation in Santa Cruz County, Arizona," Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area Research, (Tucson, AZ: Center for Desert Archaeology Projects, 2005). An expanded discussion is available online at http://www.cdarc.org/pdf/scnha_pred_mod.pdf

7. David A. Gregory, ed., Excavations in the Santa Cruz River Floodplain: The Early Agricultural Period Component at Los Pozos, Anthropological Papers No. 21 (Tucson, AZ: Center for Desert Archaeology, 2001). J.B. Mabry, ed., Archaeological Investigations of Early Village Sites in the Middle Santa Cruz Valley: Analyses and Synthesis, Anthropological Papers No. 19 (Tucson, AZ: Center for Desert Archaeology, 1998).

8. David E. Brown, ed., Biotic Communities: Southwestern United States and Northwest Mexico (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1994). William L. Deaver and Carla R. Van West, eds., El Macayo: A Prehistoric Settlement in the Upper Santa Cruz River Valley, Technical Series 74 (Tucson, AZ: Statistical Research, Inc., 2001).

9. Arthur C. MacWilliams, "The San Rafael de la Zanja Land Grant River Corridor Survey, Volume 1," Report Submitted to Arizona State Parks, 2001.

10. James I. Ebert and Timothy A. Kohler, "The Theoretical Basis of Archaeological Predictive Modeling and a Consideration of Appropriate Data-Collection Methods," in Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling, ed. W. James Judge and Lynne Sebastian (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1998), 97-172.

11. Vince Gaffney and P. Martijn van Leusen, "Postscript – GIS, Environmental Determinism and Archaeology: A Parallel Text," in Archaeology and Geographical Information Systems: A European Perspective, ed. Gary Locke and Zoran Stancic (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1995), 27-41. Timothy A. Kohler and S.C. Parker, "Predictive Models for Archaeological Resource Location," in Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 9, ed. Michael B. Schiffer (New York, NY: Academic Press, 1986), 397-452.

12. Kohler and Parker, 42.

13. Lynne Sebastian and W. James Judge, "Predicting the Past: Correlation, Explanation, and the Use of Archaeological Models," in Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling, ed. W. James Judge and Lynne Sebastian (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1988), 1-18.

14. Jeffrey H. Altschul, "Significance in American Cultural Resource Management: Lost in the Past," in Heritage of Value, Archaeology of Renown, ed. Clay Mathers, Timothy Darvill, and Barbara J. Little (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2005), 192-210.

15. William D. Lipe, "Value and Meaning in Cultural Resources," in Approaches to the Archaeological Heritage: A Comparative Study of World Cultural Resource Management Systems, ed. Henry Cleere (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 1-11. See also John Carman, "Where the Value Lies: The Importance of Materiality to the Immaterial Aspects of Heritage," in Taking Archaeology Out of Heritage, ed. Emma Waterton and Laurajane Smith (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 192-208.

16. P. Martijn van Leusen, "GIS and Archaeological Resource Management: A European Agenda," in Archaeology and Geographical Information Systems: A European Perspective, ed. Gary Locke and Zoran Stancic (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1995), 27-41. Martin Carver, "On Archaeological Value," Antiquity 70 (1996): 45-56.

17. Laurajane Smith, Archaeological Theory and the Politics of Cultural Heritage (New York: Routledge, 2004). Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (New York, NY: Routledge, 2006).

18. Alain Schnapp, The Discovery of the Past (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997).

19. Martin Carver, "On Archaeological Value," Antiquity 70 (1996): 45-56. See also Clay Mathers, John Shelberg, and Ronald Kneebone "'Drawing Distinctions': Toward a Scalar Model of Value and Significance," in Heritage of Value, Archaeology of Renown, ed. Clay Mathers, Timothy Darvill, and Barbara J. Little (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2005), 159-191.

20. Laurajane Smith, Archaeological Theory and the Politics of Cultural Heritage (New York, NY: Routledge, 2004). Nina Swidler, Kurt Dongoske, Roger Anyon, and Alan S. Downer, eds., Native Americans and Archaeologists: Stepping Stones to Common Ground (Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 1997).

21. Clay Mathers, Timothy Darvill, and Barbara J. Little, eds., Heritage of Value, Archaeology of Renown: Reshaping Archaeological Assessment and Significance (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2005). Emma Waterton and Laurajane Smith, eds., Taking Archaeology Out of Heritage (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009).

22. Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (New York, NY: Routledge, 2006).

23. Vince Gaffney and P. Martijn van Leusen, "Postscript – GIS, Environmental Determinism and Archaeology: A Parallel Text," in Archaeology and Geographical Information Systems: A European Perspective, ed. Gary Locke and Zoran Stancic (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1995), 27-41.

24. P. Martijn van Leusen, "GIS and Archaeological Resource Management: A European Agenda," in Archaeology and Geographical Information Systems: A European Perspective, ed. Gary Locke and Zoran Stancic (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1995), 27-41. Christopher D. Dore and LuAnn Wandsnider, "Modeling for Management in a Compliance World," in GIS and Archaeological Predictive Modeling: Large-scale Approaches to Establish a Baseline for Site Location Models, ed. Mark Meher and Konnie L. Wescott (Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2005), in press.

25. K. Anne Pyburn and Richard R. Wilk, "Responsible Archaeology is Applied Anthropology," in Ethics in Archaeology: Challenges for the 90's, ed. Mark J. Lynott and Alison Wylie (Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology, 1995), 71-76. Jonathan Marks, Why I Am Not A Scientist: Anthropology and Modern Knowledge (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009).

26. Kenneth L. Kvamme, "Computer Processing Techniques for Regional Modeling of Archaeological Site Locations," Advances in Computer Archaeology (1983): 1:26-52. Sandra Parker, "Predictive Modeling of Site Settlement Systems Using Multivariate Logistics," in For Concordance in Archaeological Analysis: Bridging Structure, Quantitative Technique and Theory, ed. Christopher Carr (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 1985), 173-207. Robert E. Warren, "Predictive Modelling of Archaeological Site Location: A Case Study in the Midwest," in Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology, ed. Kathleen M. S. Allen, Stanton W. Green, and Ezra B. W. Zubrow (London, UK: Taylor and Francis, Ltd., 1990), 201-215.

27. For example see Kenneth L. Kvamme, "Determining Empirical Relationships Between the Natural Environment and Prehistoric Site Locations: A Hunter Gatherer Example," in For Concordance in Archaeological Analysis: Bridging Structure, Quantitative Technique and Theory, ed. Christopher Carr (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 1985), 208-238. D.L. Carmichael, "GIS Predictive Modelling of Prehistoric Site Distributions in Central Montana," in Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology, ed. Kathleen M. S. Allen, Stanton W. Green, and Ezra B. W. Zubrow (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1990), 216-225. Richard B. Duncan and Kristen A. Beckman, "The Application of GIS Predictive Site Location Models Within Pennsylvania and West Virginia," in Practical Applications of GIS for Archaeologists: A Predictive Modeling Toolkit, ed. Konnie L. Westcott and R. Joe Brandon (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2000), 33-58. R.E. Warren and D.L. Asch, "A Predictive Model of Archaeological Site Location in the Eastern Prairie Peninsula," in Practical Applications of GIS for Archaeologists: A Predictive Modeling Toolkit, ed. K. L. Westcott and R. J. Brandon (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2000), 5-32.

28. Carole L. Crumley and William H. Marquardt, "Landscape: A Unifying Concept in Regional Analysis," in Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology, ed. Kathleen M. S. Allen, Stanton W. Green, and Ezra B. W. Zubrow (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1990), 73-79. Kathleen M.S. Allen, "Considerations of Scale in Modeling Settlement Patterns Using GIS: An Iroquois Example," in Practical Applications of GIS for Archaeologists: A Predictive Modeling Toolkit, ed. Konnie L. Westcott and R. Joe Brandon (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2000), 101-112.

29. ArcHydro.

30. Edward F. Castetter and W.H. Bell, Pima and Papago Indian Agriculture, Inter-Americana Studies I (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1942). Henry F. Dobyns, From Fire to Flood: Historic Destruction of Sonoran Desert Riverine Oases (Socorro, NM: Ballena Press, 1981).

31. A quantity reflecting the total accumulated flow within a given radius rather than precisely at a given location.

32. Sarah H. Schlanger, "Recognizing Persistent Places in Anasazi Settlement Systems," in Space, Time, and Archaeological Landscapes, ed. Jaqueline Rossignol and LuAnn Wandsnider (New York, NY: Plenum Press, 1992), 91-112.

33. Fred L. Nials, David A. Gregory, and J. Brett Hill, "The Stream Reach Concept and the Macro-Scale Study of Riverine Agriculture in Arid and Semi-Arid Environments," Geoarchaeology (2011).

34. Kenneth L. Kvamme, "Development and Testing of Quantitative Models," in Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling, ed. W. James Judge and Lynne Sebastian (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1988), 325-428.

35. Kenneth L. Kvamme, "Using Existing Archaeological Survey Data for Model Building," in Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling, ed. W. James Judge and Lynne Sebastian (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1988), 301-323. Federica Massagrande, "Using GIS with Non-Systematic Survey Data: The Mediterranean Evidence," in Archaeology and Geographical Information Systems: A European Perspective, ed. Gary Locke and Zoran Stancic (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1995), 55-65.

36. Mathers and colleagues (2005) noted the frequently unrepresentative nature of sites currently listed on the National Register, and implications for heritage management and relations among diverse communities of interest.

37. Jeffrey H. Altschul, "Models and the Modeling Process," in Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling, ed. W. James Judge and Lynne Sebastian (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1988), 61-96. "Red Flag Models: The Use of Modelling in Management Contexts," in Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology, ed. Kathleen M. S. Allen, Stanton W. Green, and Ezra B. W. Zubrow (London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd., 1990), 226-238.

38. Kenneth L. Kvamme, "Development and Testing of Quantitative Models," in Quantifying the Present and Predicting the Past: Theory, Method, and Application of Archaeological Predictive Modeling, ed. W. James Judge and Lynne Sebastian (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, 1988a), 325-428.

39. Center for Desert Archaeology, "Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area Feasibility Study," Draft Feasibility Study for submission to United States Congress. Available online at: http://www.cdarc.org/what-we-do/national-heritage-area-initiatives/the-santa-cruz-valley-national-heritage-area/feasibility-study-for-the-santa-cruz-valley-heritage-area/