Exhibit Review

The Style of Power: Building a New Nation

The University of Virginia, Small Special Collections Library, Mary and David Harrison Institute for American History, Literature, and Culture, Charlottesville, VA; Project Coordinators and curators: Mercy Quintos and Martha Hill

Temporary

The Style of Power frames the earliest cultural, social, and architectural achievements of the United States within a modestly sized but rich assemblage of cultural artifacts and documents from several institutions and collections. Cultural resource professionals will quickly notice that the exhibit curators have struck that rare balance between a vital cache of objects and a compelling narrative, each of which charts America's rapid development from a pre-Revolutionary backwater to an ambitious and industrious nation. The act of "building," as the title of the exhibit suggests, is presented as both an architectural enterprise and a kind of cultural praxis.

All architecture is willful, but there is a difference between willful expression and a sense of purpose to justify that expression. A majority of The Style of Power is dedicated to documenting how that sense of purpose was established, first through the scholarly pursuits of a new American elite that were heirs to the European aristocracy only in intellectual acumen, not in entitlement. The exhibit opens with the "Education of a Gentleman," "A Classical Education," and the "Age of Reason," that outline the Enlightenment's influence on a generation of talented minds and innovative aesthetes. Among the items in this section are early reprints of the 17th-century British philosopher John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, his contemporary Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan, and a first edition of the 18th-century Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations. Thus, the rhetoric of Reason became the rhetoric of the new Republic, but not without considerable debt to 18th- and early 19th-century women writers Judith Sargent Murray, Mercy Otis Warren, and Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved African, whose poems and tomes are identified as a more literary, but no less empirical, contribution to the intellectual production of the new nation.

The second phase of building in the exhibit, which gives The Style of Power its name, outlines how the "evanescence of social status" and matters of "good taste" were achieved through specifically British appropriations and other antiquarian pursuits. The importation of luxury goods as a means of relocating "taste" into the homes of the American social elite is cleverly juxtaposed with a first edition of Alexander Pope's Of False Taste, in which context—not associationism—is identified as the road to "good taste." However, the jewels of the exhibit are several large folios that were influential in deploying Palladian ideals among the American cognoscenti. Included are a reprint of Daniele Barbaro's 1567 M. Vitruvii Pollionis De Architectura Libri decem, the 1715 edition of Giacomo Leoni's The Architecture of A. Palladio, the 1759 edition of William Chambers's A Treatise on Civil Architecture, Johann Joachim Winckelmann's 1764 Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums, and Antoine Babuty Desgodetz's 1779 Les édifices antiques de Rome. These texts, of course, have individual histories and a much broader reach than the United States, but to see them together under the aegis of a specifically American pursuit of classicism underscores just how high the new nation was willing to aim and how deeply in European history it was willing to dig to activate its lofty intentions. If Enlightenment values were the impetus for nation building as the cultural and social "style of power," then the inclusion of these folios in the exhibit speaks volumes about the means of nation-building and the power of architectural style.

|

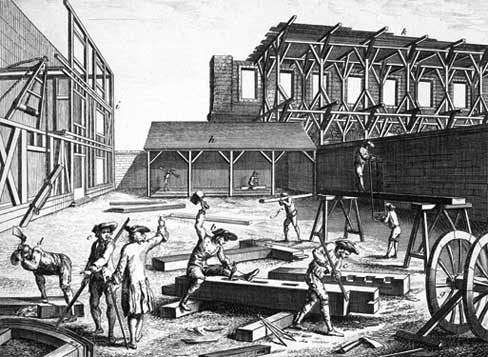

The illustration, "Charpente," appearing in the Frenchman Denis Diderot’s 1763 Encyclopédie, shows the many jobs involved in framing a building. (Courtesy of the University of Virginia.) |

|

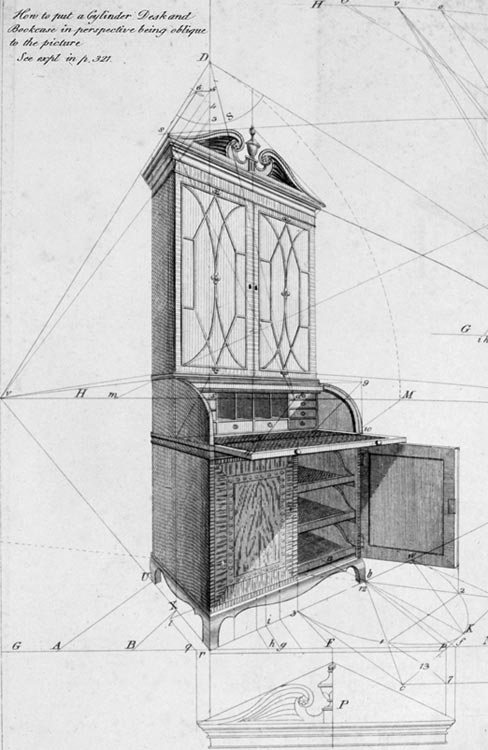

This design for a desk (right) by Thomas Sheraton accompanied a Sheraton-style desk in the exhibit. (Courtesy of the University of Virginia.) |

The final third of the exhibition is about the translation of ideas on paper into physical edifices. The exigencies of building in the early years of the United States belied any notion of a universal method, as regional vernaculars continued to flourish and the acumen of local craftsmen and builders varied from one location to the next. However, the "Civic Order" and "Civil Architecture" of the period had to be unified. After 1783, Washington, DC, and newly minted states needed capitol buildings that could intelligently interpret contemporary European architecture and, more importantly, bespeak an American integrità civica. Of course, Thomas Jefferson, the architect Charles Bulfinch, and Frenchman Charles-Louis Clérisseau figure prominently in this proposition, but The Style of Power smartly relays how the contemporary economic conditions allowed these civic buildings to take shape. The "grain-fed prosperity of the 1790s" was a function of both the exportation of goods to Europe and a steady influx of economic refugees. The inexorable equation of the 1790s, then, became money plus talent equals an architectural production rivaled only by intellectual production. Underscoring this equation is the 1800 edition of Benjamin Franklin's The Way to Wealth that, in this particular context, is a pocket-sized treasure that speaks volumes about the industriousness and ingenuity that would come to define the next century.

Even if this "style of power" worked on the scale of civic architecture and national ideologies, this exhibit thoroughly documents how it worked on the domestic scale. In viewing the folios on display we cannot help but be drawn into the fluorescence of their renderings, but we understand them as objects that speak about quiet study, perhaps at a Sheraton-style secretary. In seeing an Adamesque dining chair, we understand the ubiquity and cross-Atlantic popularity of Robert and James Adams' 1773 Works, but know it to be something for daily use in the home. In seeing a page of Jefferson's 1786 notes from his tour of English county seats, we see how they translate into civic ideals for a new nation, but we also understand them to be intimate notations so well preserved that they could have been written yesterday. Nation-building must be imbued with a strong architectural program, the right economic conditions, and a talented workforce. But, as The Style of Power attests, nation-building begins with an individual commitment to the idea of a nation as much as the reality of one.

William Richards

University of Virginia