Research Report

The Freedmen's Bureau Records Project at the National Archives

by Cynthia Fox and Budge Weidman

An unparalleled source of information on black life in the late 1860s and 1870s, the Freedmen's Bureau records at the National Archives in Washington, DC, document the Federal Government's treatment of emancipated slaves in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. For all their value, deterioration due to age and the lack of microfilm copies and a name index had rendered the records difficult to use. To remedy this problem, Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau Records Preservation Act of 2000, authorizing the Archivist of the United States to preserve the records for future generations and to establish partnerships with Howard University and other institutions for the purposes of indexing them and making them more accessible to the public.(1)

The National Archives' Freedmen's Bureau Preservation and Access Project team, established in 2001, included archivists, editors, conservators, microfilm specialists, and Civil War Conservation Corps (CWCC) volunteers.(2) Over five years, the team has preserved and microfilmed 1.2 million pages of Freedman's Bureau records, including city, county, and state field records of the District of Columbia and the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.(3)

Bureau assistant commissioners in these former Confederate states, border states, and the District corresponded extensively with the Washington bureau headquarters and subordinate officers in the cities and counties over the bureau's brief history. This bureaucracy generated thousands of reports, correspondence, and supporting materials. The assistant commissioners received many letters from freedmen, local white citizens, state officials, and other federal agencies on topics ranging from complaints to employment applications.

History of the Freedmen's Bureau

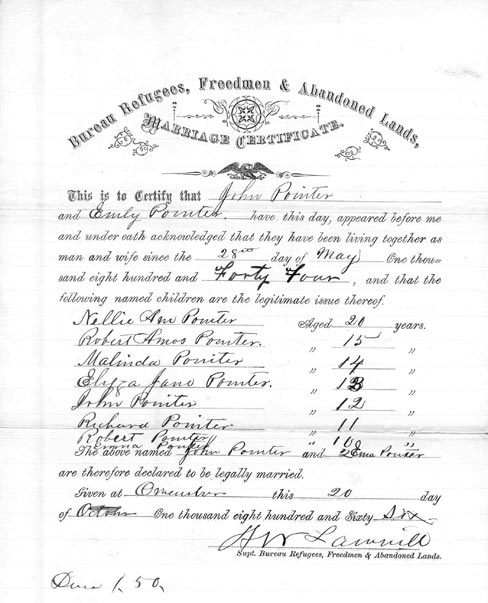

Congress established the Freedmen's Bureau within the War Department on March 3, 1865.(4) In May of that year, President Andrew Johnson appointed Major General Oliver Otis Howard as bureau commissioner, a position Howard held until the bureau's termination. Although the bureau's early activities involved the supervision of abandoned and confiscated property, helping former slaves transition into "normal" society was its primary mission. Bureau officials issued rations and clothing, operated hospitals and refugee camps, and supervised labor contracts. They handled apprenticeship disputes and complaints, assisted benevolent societies in the establishment of schools, helped freedmen legalize marriages entered into during slavery, and provided transportation for refugees and freedmen attempting to reunite with family or relocate to other parts of the country.(5)(Figure 1)They also helped black soldiers and sailors of the United States Colored Troops and their heirs collect bounty claims, pensions, and back pay. The great social experiment virtually ended in July 1868 when Congress ordered the suspension of most bureau operations.(6)

For the next year and a half, the bureau continued to pursue its education work and process claims. In the summer of 1870, it withdrew its superintendents of education from the states and greatly reduced its headquarters staff. From that time until its dissolution on June 30, 1872, the bureau focused almost exclusively on the disposition of claims.(7) Its records and remaining functions were transferred to the Freedmen's Branch in the office of the Adjutant General. The records of this branch are among the bureau's files.

The Documents and Their Stories

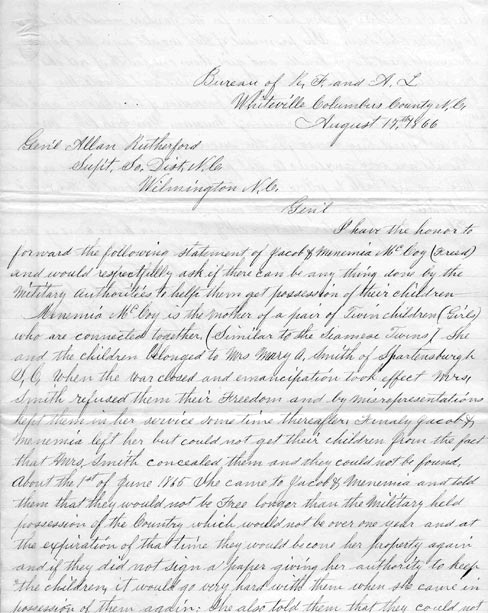

The Freedmen's Bureau was an unusual social experiment for the Federal Government, and the stories preserved in the bureau's records are unique and personal. Jacob and Menemia McCoy, former slaves, approached the Wilmington, North Carolina, bureau office in 1866 for help regaining custody of their conjoined twin daughters.(Figure 2) Prior to emancipation, Menemia McCoy and the children were the property of Mary A. Smith of Spartansburg, South Carolina. The Bureau officer wrote—

When the war closed and emancipation took effect Mrs. Smith refused them their Freedom and by misrepresentations kept them in her service sometime thereafter. Finally Jacob and Menemia left her but could not get their children from the fact that Mrs. Smith concealed them and they could not be found. About the 1st of June 1865 she came to Jacob and Menemia and told them that they would not be free longer than the military held possession of the country which would not be one year and at the expiration of the that time they would become her property again and if they did not sign a paper giving her authority to keep the children it would go very hard with them when she came in possession of them again.(8) |

The Freedmen's Bureau records shed new light on the story told in the so-called official autobiography of the twins, known as Millie-Christine. Born into slavery in North Carolina in 1851, Millie and Christine had been exhibited by Mary Smith's husband, J.P. Smith, prior to the Civil War. Smith died in 1862 and, according to the story, the 14-year-old girls chose to stay with Smith's widow after the war. The twins enjoyed a long and successful career as "The Two-Headed Nightingale," touring with P.T. Barnum's show and ultimately saving enough money to buy the plantation where they had been born. Millie and Christine retired from show business and lived with their parents until 1912, when they died of tuberculosis, 17 hours apart.

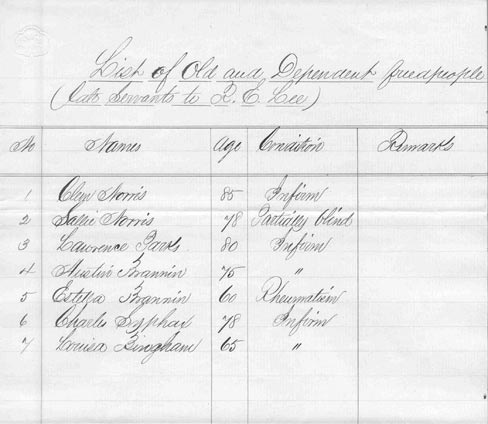

Another story preserved in the Freedmen's Bureau records involves former servants of Robert E. Lee. In August 1868, seven freed people were found destitute and living on land allotted them from the Lee estate. Bureau agent J.C. Abeel provided the assistant commissioner in Washington with a list of their names, ages, and conditions.(9)(Figure 3) Their connection to Robert E. Lee resulted in a high level discussion of their fate that included the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. They were allowed to continue to live near Freedmen's Village in northern Virginia and given fuel and rations by order of Secretary Stanton.

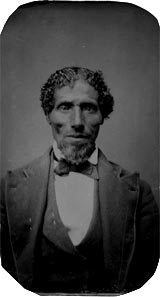

An interesting claim for an enlistment bounty, or bonus, appears in the records of the Freedmen's Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, the last remnant of the Freedmen's Bureau. Shortly after Charles Tarleton Jr. entered the 68th U.S. Colored Troops in 1864, he contracted measles and pneumonia and subsequently died. Nearly 12 years later his father, Charles Sr., a former slave, came forward to claim the enlistment bounty owed to his son.(10) The elder Charles showed up at the office of a lawyer near Hannibal, Missouri, with the son of his former owner, Edward Leister, who verified Charles Sr.'s identity. Tarlton presented a tintype photograph of himself as proof.(11) After paying the lawyer's fee, the father collected his son's enlistment bounty. That tintype photo survives, along with the written documentation, in the Freedmen's Bureau records.(Figure 4)

|

Figure 4. Charles Tarleton submitted this tintype in 1875 to prove that he was the father of a young soldier who had died at Benton Barracks, Missouri, on May 30, 1864. (Courtesy of the National Archives.) |

Next Steps

The task of indexing the documents is now underway. The National Archives has received a grant from the Peck Stacpoole Foundation in New York City to support Howard University's pilot project publishing the Freedmen's Bureau records online. The website has been launched and continues to grow as more images are added. A new partnership between Howard University and the Genealogical Society of Utah will create digital images from the microfilm and begin creating a name index to the records. The National Archives supports this goal and will continue to assist when possible in the creation of a digital publication.

About the Authors

Cynthia Fox is the chief of the Old Military and Civil Records unit at the National Archives in Washington, DC. Budge Weidman is the manager of the Civil War Conservation Corps and a volunteer at the National Archives. The website for the Howard University digital access pilot project is http://hufast.howard.edu/FreedmenKnowledgeClient/index.aspx.

Notes

1. Freedmen's Bureau Records Preservation Act of 2000, U.S. Code, vol. 44, sec. 2910 (2000).

2. The CWCC volunteers helped accomplish the massive tasks of arranging and copying nearly 1,000 cubic feet of records onto 1,131 reels of microfilm. Over the past 14 years, the CWCC has donated thousands of hours towards helping the National Archives preserve Civil War records.

3. The records of the Florida field offices were processed first under an existing partnership with Jim Cusick of the Department of Special Collections at the Smathers Library of the University of Florida.

4. Freedmen's Bureau Act of 1865, U.S. Statutes at Large 13 (1866): 507-9. Congress established the Freedmen's Bank at the same time, although the bureau and the bank existed and operated separately. See Freedman's Savings and Trust Company Act of 1865, U.S. Statutes at Large 13 (1866): 510.

5. Education was at the center of the bureau's efforts to integrate freed people into the economy. A circular issued by Commissioner Howard in July 1865 instructed the assistant commissioners to designate one officer in each state to serve as "general Superintendents of Schools." Whereas the Freedmen's Bureau helped build the schools, it fell to the parents and benevolent societies to pay the teachers.

6. Congress ordered that the commissioner of the bureau "shall, on the first day of January next, cause the said bureau to be withdrawn from the several States within which said bureau has acted and its operation shall be discontinued." U.S. Statutes at Large 15 (1868): 193.

7. U.S. Statutes at Large 17 (1872): 366.

8. Field Records for the State of North Carolina, Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (BRFAL), Entry 2879, Record Group (RG) 105, National Archives and Records Administration (National Archives), Washington, DC.

9. These same names appear on a document filed in Fairfax County, Virginia, court records. On December 29, 1862, Robert E. Lee, as the executor of his father-in-law George Custis's will, freed all the family slaves. Field Records for the State of Virginia, BRFAL Entry 3967, RG 105, National Archives.

10. The circumstances surrounding this delay are not fully explained in the records, but it may be that he had attempted to make a claim earlier but was not able to prove his relationship to the young soldier.

11. The notary public attached a note to the photograph that said, "On this 25th day of May 1875, personally came before me a notary public for Marin County, Missouri, Edward Leister who being sworn says that the above and within tintype is the precise likeness of Charles Tarleton, the father of Charles Tarlton, who was a slave and belonged to his father." Field Records for the State of Missouri, BRFAL Entry 4404, RG 105, National Archives.