Article

Gazetting and Historic Preservation in Kenya

by Thomas G. Hart

Kenya Yesterday and Today

On a fine sunny day in Nairobi in October 1927, Governor Sir Edward Grigg put pen to paper in his mock-Tudor official mansion, setting in motion historic preservation in Kenya Colony with the signature of "An Ordinance to Provide for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments and Objects of Archeological, Historical, or Artistic Interest."(1)(Figure 1)

|

Figure 1. Sir Edward Grigg signed the first Kenyan ancient monuments act into law in 1927. (Courtesy of Kenya National Archives.) |

Why adopt such legislation in Kenya in 1927? A memorandum to the law explained that the government "followed the scheme of the Indian Act," which was "the late Marquess Curzon's especial care."(2) Curzon, former Viceroy of India, was a statesman of the British Empire who died in 1925; it is likely that Kenyan colonial administrators, many from India, meant to honor him.(Figure 2) Grigg himself had been born in Madras and must have known Curzon well during his own colonial career. While Great Britain began protecting its own heritage with ancient monuments acts in 1882 and 1913,(3) the Indian crown jewel of empire produced a very different version of such legislation in 1904. The legal framework of Indian colonialism afforded a convenient model for the new (1895) British protectorate of Kenya, and this authoritarian model would mark Kenyan preservation policy.

|

Figure 2. Viceroy of India George Nathaniel Curzon and Lady Curzon, shown here about 1899, played a central role in establishing the Indian ancient monuments act that, in turn, inspired the Kenyan monuments act. (Courtesy of the British Library.) |

Kenya today is a nation of over 30 million people, about the size of Oregon and located on the east coast of Africa at the equator. It gained independence from British colonial rule in 1963. The nation enjoys a diverse and rich physical heritage consisting of paleontological sites of world importance to human origins; the sites and artifacts of the many indigenous African ethnic groups; the legacy of the unique Swahili culture born of African and Arab sources on the Indian Ocean coast; and the British colonial imprint.

Protected places and buildings in Kenya are termed "monuments"—part of the nomenclature put in place in 1927. Their registration is called "gazetting" from the practice of publishing legal notice of protected sites in the official Gazette. Kenya's system is centralized and national, run by conservation professionals, and dependent on criminal penalties to protect heritage sites. The prime keeper of Kenyan heritage is the National Museums of Kenya, with over 1,000 employees at 19 sites around the country.(Figure 3) Its stewardship responsibilities range from the epochal skulls of early man, to a 1498 pillar erected by Vasco da Gama, to the home of Baroness Karen Blixen, author of Out of Africa.(Figures 4-5) The Sites and Monuments Department within the National Museums is responsible for gazetting and other preservation functions.

|

Figure 3. Headquartered in this building in Nairobi, the National Museums of Kenya is responsible for Kenyan heritage under the Antiquities and Monuments Act. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 4. The National Museums of Kenya preserves the 1498 Vasco Da Gama Pillar at Malindi. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 5. The National Museums of Kenya manages the Karen Blixen Museum in Nairobi, the former home of the late baroness author of Out of Africa. (Courtesy of the author.) |

The system is comprehensive in the African context and has done an excellent job with archeological sites and objects despite a lack of resources, lack of public awareness, weak involvement of local communities, and the absence of economic incentives. In the last decade, however, Kenya has encountered a number of obstacles to protecting buildings still in use, particularly privately owned properties, under the gazetting system. In fact, some 19 property owners have objected to and challenged gazettement in recent years. The following critical review of Kenyan preservation policy and practice highlights some of the issues that differentiate centralized penalty-based historic preservation systems from decentralized incentive-based alternatives. It ends with some suggestions for how Kenya might adapt its historic preservation program to new challenges and changing circumstances in the 21st century.

Kenya's 1927 Ancient Monuments Act and Its Successors

The 1927 Ancient Monuments Act was the first of five successive pieces of Kenyan preservation legislation. The acts of 1934, 1962, 1983, and 2005 each repealed and replaced its predecessor, but also built on it to create a system with as much continuity as change.

The draconian and highly centralized tenets of the Indian law that were the basis for the 1927 act would not have been accepted by the British parliament or the public.(4) They seemed to suit, however, the fundamentally undemocratic nature of Kenya's colonial rule. In some ways, it resembles the utopian work of a preservationist philosopher-king, unfettered by public opinion, politics, or property owners. A comparison of the text of the 1927 act with the Indian Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904 reveals that it was adopted practically verbatim. Many sections from turn-of-the-century India remain ossified in the current statute.(5) The Indian act established a model of central government control over historic sites that endures in spirit—and often to the letter—today.

The most fundamental of the major powers of this act still in force is the power to declare protection of historic sites by announcement in the Gazette, a document akin to the Federal Register in the United States. The government is also empowered to direct control of protected sites and objects through a variety of means, including compulsory acquisition by right of eminent domain, agreements with owners, or assumption of guardianship of any unowned site or object.

The power to fine and imprison gave (and gives) the law teeth: "Anyone who destroys, removes, injures, alters, defaces or imperils a protected monument or antiquity" was guilty of a crime. The maximum fine of 100 pounds in 1927 compared to an average British salary of about 5 pounds per week, and to that of Africans of a few shillings per day. The maximum prison sentence was six months. Heritage conservation was placed squarely within the police power of government.

In 1934, the legislation was expanded to 25 sections, of which 17 were practically identical to the 1927 law.(6) The change came in response to the work of the great pioneer of human paleontology, Louis Leakey. By 1932, Leakey's Kenyan sites had established East Africa as the cradle of humankind, shattering the previous academic consensus that hominid origins lay in Asia.(7) The new sections largely addressed the needs of paleontological discoveries such as research and export permits, ownership and treatment of objects, and control of excavations at protected sites. All of the government powers were retained and, if anything, made more specific. In 1962, the winds of change presaged an end to colonial rule, and the 1934 legislation was hastily converted to the forms of the new nation, almost verbatim.(8)

Two decades after independence, Kenya had become one of Africa's success stories. Coastal tourism brought thousands of European sun-seekers to Indian Ocean beaches, where they eagerly bought (and were eagerly sold) the many relics and artifacts of the Swahili culture, created centuries ago from the cultural intermarriage of indigenous coastal Africans and Arab traders. This African Islamic culture developed the Kiswahili lingua franca of East Africa as well as a unique architecture and related arts.

The most notable Swahili sites in Kenya are the narrow old town mazes of Mombasa and Lamu, an island with no motor vehicles and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.(Figure 6) Numerous ruins of Swahili settlements dating back to the 9th century dot the coast, notably at Gedi, Takwa, Shanga, Manda, and Pate. By 1980, the elaborately carved doors and windows of the old coral houses, beds and other furniture, jewelry, and porcelain were disappearing at an alarming rate. In response, a new Antiquities and Monuments Act took effect in 1983, the work of curator-turned-politician Omar Bwana and the dynamic Museums director, Richard Leakey, son of Louis. Once again, 24 old sections were substantially recycled.

|

Figure 6. The well preserved Swahili town of Lamu on the Indian Ocean was the first gazetted historic district in Kenya and the first town to pass a local preservation ordinance. (Courtesy of the author.) |

One of the most significant changes in 1983 was the automatic protection of many sites and objects without having to gazette them individually. Under these provisions, any man-made object or structure dating from before 1895 and any Swahili door carved before 1946 are automatically protected. Only historic objects or places dating after 1895 have required gazetting. The 1983 law modified a prior emphasis on paleontology with clear mandates to protect more recent places, structures, and objects.(9)

The most recent and current legislation, the National Museums and Heritage Act (2006), was drafted to address staff restructuring and physical infrastructure for the National Museums of Kenya. For the first time, as the name implies, protection of heritage and the basic text governing the museums are combined. Most changes concern the museums.

The sections that deal with historic preservation are substantially similar to previous texts. The fundamental approach empowering the national government to protect automatically or to gazette sites and objects for protection, to administer agreements with owners, to compel lease or purchase, to issue all permits and licenses, and to fine and imprison violators remains. There is also an effort by the professionals "to limit the powers of the politicians" and avoid some of the abuses of gazettement.(10) Perhaps the most important change is "spot gazetting"—emergency protection for "any heritage…in imminent danger of serious damage or destruction."(11) The penalties for violation of the law have also been increased to one million shillings (about $13,700 in a nation with a gross national income per capita of $530 in 2005) and 12 months in prison.(12)

Kenya's Two Historic Districts

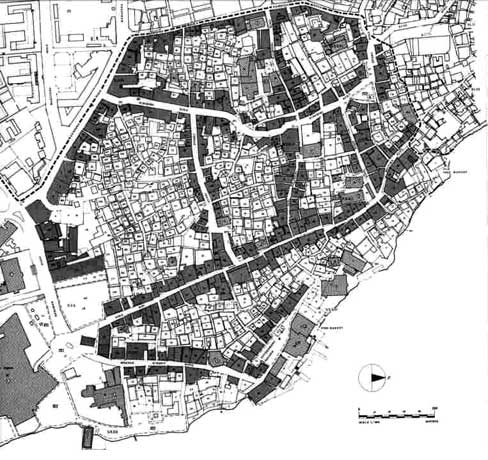

Kenya has two historic districts with local bylaws in the old town areas of Lamu and Mombasa. Lamu came to international research attention starting in the 1970s, and the entire old town was gazetted for protection in 1986, with local bylaws adopted in 1991.(13) The relatively brief bylaws—three pages in the Gazette—adopted the foreign experts' definitions and map of an inner "conservation area" and an outer "protection area."

Lamu's local planning commission consists of three local and eight central government officials. The commission is charged with reviewing all applications to alter buildings or change use or user, making recommendations on building permits, coordinating plans for public areas, and providing technical advice on approved construction. The demolition of coral buildings or any feature in the conservation areas is prohibited. Any alteration is subject to prior approval by the commission, as are any signs or advertisements.

In many ways, the Lamu Planning Commission has been a success. A European Union grant to restore 10 houses launched it to much local appreciation. Citizens are accustomed to having building and other projects reviewed.(14) On the other hand, certain violations (unsuitable signs, encroachment on the waterfront) by influential local businesses have been allowed to stand. Locally authorized fines and imprisonment have never been imposed.

Preservation bylaws based on the Lamu model were decreed for Mombasa in 1996.(15)(Figure 7) Oddly, the conservation commission was not appointed and did not meet for the first decade of the Mombasa bylaws.(16) Rather, the Mombasa Old Town Conservation Office (MOTCO), an office of the National Museums with a staff of three, took charge. Since then, MOTCO has succeeded in getting the property tax rate on homes in the conservation area halved, thwarting a casino project in the old port of Mombasa; preserving public seafront, and blocking the construction of large diesel oil tanks at the old port.(17) MOTCO can also point to restored balcony houses, improvements fronting Fort Jesus, and newly paved roads and alleys. The Mombasa Conservation Commission has finally been appointed and met recently.

|

Figure 7. Mombasa Old Town was the second gazetted historic district in Kenya. (From Joseph King and Donatella Procesi, Conservation Plan for the Old Town of Mombasa, Kenya [1990].) |

Unlike historic districts in other countries, the Lamu and Mombasa historic districts do not have historic building plaque programs, detailed building and rehabilitation guidelines, or integrated "main street" development programs. There are currently no mechanisms in place for proposing local landmarks or new districts, or for holding public meetings for architectural review.

Gazetting Procedures and Trends

How does a place become a protected monument? Briefly, the National Museums of Kenya makes a recommendation to the minister of culture and heritage. The Minister then signs the notice and sends it to the attorney general for publication in the Kenya Gazette.

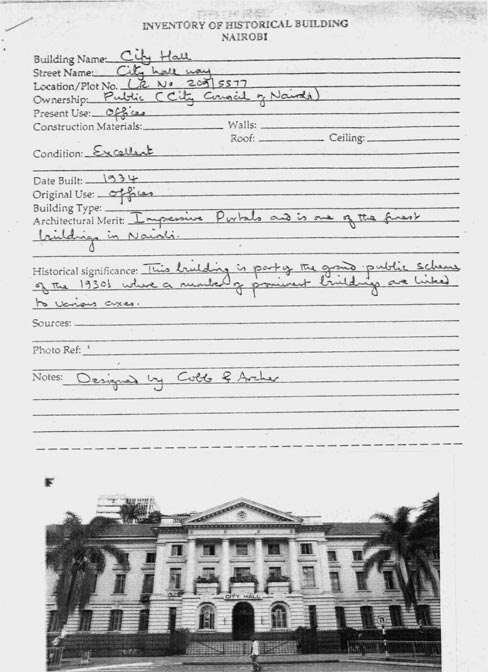

Today, the gazetting process begins as five researchers of the National Museums of Kenya's Sites and Monuments Department compile regional catalogues of sites worthy of protection.(18)(Figure 8) The resulting eight loose-leaf "inventories," one for each province in Kenya, consist of two-page inventory forms for each building.(Figure 9) The criteria of the inventory forms appear to have their roots in those used by the American-educated Italian scholar Francesco Siravo in his survey of old town Mombasa in the late 1980s.(19) Thus, the Kenyan use of architectural merit, historical period, association to significant events, the 50-year rule, and condition—all also criteria for the National Register of Historic Places in the United States—form one of the few parallels between the Kenyan and American models.

|

Figure 8. Documentation of historic sites and proposals for gazetting begins at the Sites and Monuments Department research section at the National Museums of Kenya. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 9. The National Museums of Kenya produces and maintains inventory forms for historic buildings. (Courtesy of the National Museums of Kenya.)

|

Posted and published notice is required to ensure that owners have an opportunity to object to the gazettement, which they may do within one month, but otherwise there is generally no other public input or consultation in the gazetting process. Individual citizens and local governments may not submit gazettement proposals directly to the ministry. The Sites and Monuments Department must first make a determination, which results in less public input but greater curatorial and professional control over the process.

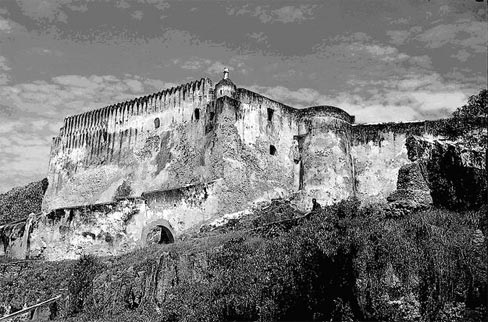

The first list of officially gazetted antiquities and monuments was published on March 19, 1929.(20) Of the 18 listings, 15 were Portuguese or Swahili (often referred to as "Arab") ruins on the Indian Ocean coast, 2 were tribal sacred sites, and 1 was prehistoric. All of the 1929 listings remain gazetted today.(Figure 10) By 1935, the list had grown to 23, with Louis Leakey's activities reflected in the addition of the Kanam-Kanjera fossil beds near Lake Victoria. In the 1950s, the coastal antiquities warden for the Kenyan National Park Service, James Kirkman, began serious research on the lost cities of the Swahili civilization, contributing 40 gazettings of monuments on the coast between 1954 and 1959.(21)

|

Figure 10. Built by the Portuguese between 1593 and 1597, Fort Jesus at Mombasa was one of the first gazetted monuments. (Courtesy of the National Museums of Kenya.) |

The arrival of Martin Pickford at the National Museums of Kenya in 1978, where he established and headed the Department of Sites and Monuments, marked a watershed. By Pickford's own account, Museums director Richard Leakey was also instrumental in directing attention to many coastal ruins and prehistoric sites during this period.(22) A comprehensive list dating from about 1983, apparently the work of Pickford, listed 79 inland and coastal monuments by that date.(23) In addition to the ever-growing lists of coastal ruins and prehistoric remains, something new appeared on that list: two historic buildings of relatively recent date, still standing and in use. The Italian Church at Kijabe, an architectural gem built by talented Italian prisoners in World War II, was gazetted in 1981, and the house of Jomo Kenyatta, father of independent Kenya, in 1977.

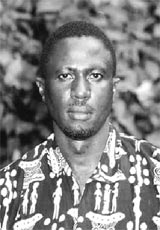

With the departure of Pickford and the adoption of blanket protections in 1983, gazetting fell into a lull for nearly a decade. The appointment of George Abungu as head of coastal archeology in 1990, later to be director of regional museums from 1996 to 1999 and general director of the National Museums of Kenya from 1999 to 2002, marked renewed gazetting activity and emphasized further areas of interest such as cultural landscapes, landmarks of the independence struggle, and buildings of the colonial era.(24)(Figure 11)

|

Figure 11. George Abungu was responsible for the new directions in Kenyan heritage protection in the last decade. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Thus an increase, as well as a change of direction, in protected properties has occurred since 1990. This group includes a large number of indigenous Kenyan cultural sites, notably the Mukurwe-wa-Nyagathanga shrine, the Bedida and Mrima sacred groves, and 34 kayas, the sacred vales of the Miji Kenda people. Landmarks of the independence struggle have been protected recently as well, including Dedan Kimathi's trench and three other Mau Mau sites. Most notably similar to the American experience, conventional urban buildings over 50 years old are now included in significant numbers. The gazetting of the Old District Officer's building in Malindi in 1991 broke the ice for what now comprises a group of over 70 colonial-era structures, including government offices, churches, schools, clubs, and commercial buildings.

What caused the new directions in Kenyan preservation? One must first note that the introduction of blanket protections in 1983 reduced the urgency of individually protecting the prehistoric sites and Swahili ruins that formed the majority of the gazetted list up to then. The growing number of educated indigenous Kenyans in museum service by the 1990s no doubt contributed to interest in tribal sacred sites as well as Mau Mau landmarks. As for the buildings of the colonial period, the opening of the University of Nairobi's architecture school in 1975 led to the study and appreciation of urban buildings (evidenced by the number of master's theses on the topic) by budding Kenyan architects, several of whom joined the Museums' staff.(25) Further, the work of international researchers on historic Lamu Town made local staff aware of the importance of protecting inhabited buildings and urban areas. Many of the current leaders of preservation in Kenya began as understudies to the expatriates directing the Lamu research.(26)

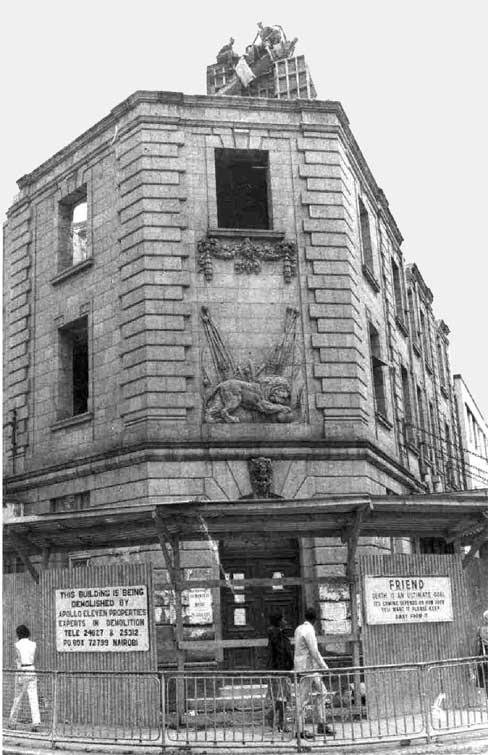

Mzalendo Kibunjia, the present director of sites and monuments, also notes that before the building boom of the seventies and eighties, older buildings were simply not in danger. Such cases as the 1982 razing of Nairobi House, the former headquarters of the Imperial British East Africa Company, caused considerable controversy.(27)(Figure 12)

|

Figure 12. The 1982 demolition of Nairobi House called public attention to the loss of historic buildings in Kenya. (Courtesy of The Nation [Nairobi], 1982.) |

Degazettement

In certain cases, protected status has been removed from a site by a new Gazette notice, thereby revoking the previous declaration as a monument. The Mama Ngina Drive area of Mombasa, a public waterfront park containing archeological remnants of the city's foundation, was degazetted in 1993.(28) Politically influential individuals had planned to degazette the oceanfront property, get it allocated to them by the lands office, and resell it at enormous profit to commercial developers. They encountered unexpected opposition from local groups, including the Friends of Fort Jesus and the Muslim Human Rights League (MUHURI), and had to abandon their plans.

Gazetted in 1997, the Railway Staff Quarters are a group of stone bungalows built in the 1920s for junior European railway staff in Nairobi. A well-connected entrepreneur had the commercially desirable eastern end of the property, on a busy intersection, reallocated in order to resell it to an Asian entrepreneur. Degazettement of the prime plot ensued, and the houses on the eastern side have been razed.(29) Similar cases of degazettment of declared monuments include Nairobi City Park, Lord Edgerton's stone country house, and Westminster House, a 1928 neoclassical office building in the central business district. Yet, the Kenyan preservation system is hardly a paper tiger, and several success stories exist.

The staff of the National Museums in Mombasa awoke one morning in 1997 to find their own parking lot adjacent to the Old Law Courts being excavated for a new bank. Although publicly owned and within the boundaries of the gazetted Old Town Mombasa area, title to the plot passed into the hands of foreign banking interests. The Museums succeeded in halting construction.(30)

In 1999, the Museums succeeded in halting unauthorized work at 17th-century Portuguese Fort St. Joseph in Mombasa, one of the first sites gazetted in 1929. Developers had acquired the land through a questionable title reallocation and started work on a hotel, posting spear-wielding Maasai guards who refused entry even to the judge hearing the Museums' case.(31) Another relatively successful case stopped the destruction of the historic tomb of Bwana Zahidi Ngumi in the gazetted Old Town Lamu district in 1999.(32) In the early 1990s, a New York antiques dealer was caught with "a lorry load" of Lamu antiquities. He was taken to court, found guilty, and fined.(33) These successes not withstanding, with a single lawyer in the legal department of the National Museums of Kenya, initiating legal action is constrained not only by the desire to avoid antagonizing the public, but also by workload factors. As in so many other countries, there is a mismatch between a protection system based on direct legal sanctions and the personnel available to enforce it.

The government's right to acquire historic places from private owners by compulsory purchase has been carried out only twice. The first instance was for the Lamu Museum in 1975.(Figure 13) The property was owned by the Busaidi family, formerly the liwalis (traditional rulers) of Lamu, whose house had been expropriated by the British district commissioner at the turn of the century. The family wanted it back after independence but was forced to sell to the Museums.(34) The second use of compulsory purchase was the acquisition of what is now the Old German Post Office Museum in Lamu in 1988.(35)

|

Figure 13. The government acquired the Lamu Museum, formerly the residence of Lamu's traditional rulers (liwalis) and colonial district officers, by compulsory purchase in 1975. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Objections to Gazettement and Concerns about Alterations

As Kenya has turned to the recognition of a broad range of monumental and utilitarian buildings, owner objections are a growing concern. The 19 objections since 1997 reveal not only a misunderstanding of the law and a need for a nationwide public education strategy, but also the paradox of central government protection in a climate universally suspicious of government motives. In most cases, owners have objected because they believed that gazettement meant their property would be taken by the state, or that no further alterations to their properties could be undertaken, or that it would interfere with their accustomed use of the property. The Presbyterian Church, for example, wrote to ask "what it means…in terms of ownership" for two gazetted churches.(36) The lawyer for the owners of Imperial Chambers cited several examples of old buildings "demolished and allocated to politically correct individuals," writing that their clients "are apprehensive whether this is prelude to similar exercise."(37) The owners of the so-called Karen Blixen House in Naivasha confided that they "did not know what" the government was "up to."(38) The University of Nairobi was reassured over ownership of the Chiromo House by the Museums' legal officer, and the director of sites and monuments personally handled a worried call from the head of Nairobi School, who assumed the government was taking over.(39)

Five of the objections cited constraints on altering or enlarging their properties as the main concern. Old Mutual's written complaint noted "major refurbishment of this property" and objected to gazettement "because it is so unclear what you can do and can't do under the historic building scenario."(40)(Figure 14) Standard Chartered Bank's objection included "the restriction on making alterations under section 23 of the Act," as did the owners of Imperial Chambers, who had drawn up a remarkably sympathetic expansion to six stories, maintaining the historic stone façade.(41)(Figure 15) Similar concerns were voiced by the Bull Café, "being reconstructed into a modern building."(42) St. Peter's Anglican Church in Nyeri was concerned about the "need to renovate and reconstruct."(43)

|

Figure 14. The owner of the Old Mutual building in Nairobi is concerned that gazettement will impede redevelopment and lower property values. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 15. The owners of the Standard Chartered Bank in Nairobi object to restrictions on alterations and dispute the building's historic character. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Although Section 23 of the Act establishes penalties for anyone who "destroys, removes, injures, alters or defaces" a monument, the actual policy is much more flexible.(44) The Sites and Monuments Department, while retaining the right to be consulted on alterations, is "mainly interested in the exterior façade" of historic buildings and will accept sympathetic changes, as in the cases of Grindlay's Bank and the Royal Casino in Mombasa.(45)

Some property owners objected to gazettement on the grounds that their properties did not meet the "historic interest" qualification. Such was the case with Standard Chartered Bank.(46) In the case of Bohra Mosque, the congregation pointed out that the mosque itself was pulled down and rebuilt in 1980, and only the ornate old gateway was original.(47) [They have since agreed to gazette the gate.] Imperial Chambers, the Blixen House in Naivasha, and Grindlay's Bank made similar arguments.(Figure 16)

|

Figure 16. The Blixen House in Naivasha, shown here in 2001, is under consideration for gazettement. (Courtesy of Tove Hussein.) |

Owners of three properties (the Nairobi School, Bohra Mosque, and the Surat District Association) expressed concerns about gazettement interfering with use, assuming the public would henceforth have access.(Figure 17) In fact, they had nothing to fear, since under the heritage law public access does not apply to privately owned property. "The public shall have right of access" only to "a monument which is for the time being owned by the National Museums Board or by another authority."(48) In addition to this protection, the Bohra and Surat buildings—the legacy of groups of railway laborers imported from British India—are protected under the Act's special status for religious structures, in language dating from the 1904 Indian law: "When any monument…is used periodically for religious observances, the authority shall make due provision for the protection of the monument from pollution or desecration…by prohibiting entry therein, except in accordance with by-laws made with the concurrence of the persons in religious charge of the monument."(49) The contentious tangle of Indian religions under the Raj created a text now relevant to two such groups a century later on another continent.

|

Figure 17. The members of the Surat District Association in Nairobi are concerned that gazettement will mean public access to their private religious ceremonies. (Courtesy of the author.) |

A barrage of letters of objection in late March and early April 2001 took the Museums by surprise. Officials met with or talked to several objectors, and the Museums also took the step of publishing a "Monuments Declaration" in the newspapers "in view of the anxiety caused to some of the owners."(50) In concise bullet points the notice clarified the policy on ownership, public access, alterations, and other issues, and promoted the benefits of gazettement, such as "recognition of the uniqueness of the property" and "potential assistance" from donors.(51) More significantly, the Ministry now requires the Sites and Monuments Department to consult with owners and present evidence of their agreement when sending a draft gazette notice to the Ministry.(52)

Conclusion

The confusion over the owners' ability to alter their properties points to the need for community supported and administered local preservation ordinances with detailed guidelines for alterations. Currently, the national Act requires no such standards for ordinances or guidelines, and even the existing Lamu and Mombasa ordinances are vague.

When fully informed of the benefits of being listed in the National Register of Historic Places, owners of property in the United States and its territories are more likely to support registration because such recognition now opens the door to a variety of national, state, and local financial incentives.(53) The historian Robert Stipe has noted that—

The American system of preservation…accepts at the outset that the core of the problem of preserving old buildings and neighborhoods is simply a matter of economics. If preservation efforts are to succeed, respect for what is called the owner's bottom line is of paramount importance.(54) |

In contrast to this approach, the Kenyan gazetting system emanates exclusively from the academic conservation and research concerns of the National Museums of Kenya. The Kenyan approach sufficed in the colonial period, when the public had little say, and in the case of paleontological and archeological finds on public land, where the American system is not very different.(55) It worked reasonably well with coastal sites and ruins, although some clashes with local owners and inhabitants occurred. But more recently, when dealing with living communities like Lamu and Mombasa, or with colonial-era buildings still in use, Museums officers responsible for conservation recognize the role economic incentives can play in their preservation efforts.(56)

Kenya's highly centralized heritage preservation system has met with much success in a difficult African context. The efforts of conservation officers are often near heroic. But Kenya is a developing nation. It is difficult to imagine that major new government resources will be available to the Museums any time soon. For this reason off-budget, decentralized strategies such as tax and investment incentives may be particularly practical alternatives to seeking scarce funds from parliament. The National Museums have recognized the value of moving toward a mixed system that includes economic incentives for historic preservation. The Museums are currently working with the new Ministry of Culture and Heritage to draft a series of changes that will guide preservation in Kenya in the future.

About the Author

Thomas G. Hart is a historic inspector on the Old Executive Office Building modernization project in Washington, DC. He previously worked as a foreign service officer assigned to the United States Embassy in Nairobi, Kenya.

Notes

1. Government of the Crown Colony of Kenya, The Official Gazette (hereafter cited as Gazette) (1927), Ord. 17.

2. Gazette (1927), 687.

3. John Delafons, Politics and Preservation: A Policy History of the Built Heritage (London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall, 1997), 25, 30, 31.

4. In the 1913 British Ancient Monuments Act, for example, no penalties for damaging a monument may be levied on its owners; the Indian and Kenyan laws could (and can) fine or imprison owners for altering their own property. Further, punishments were less severe in Britain: a maximum of 5 pounds versus 100 in Kenya, and one month's maximum jail sentence versus six months.

5. Government of India, The Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of 1904, Indian Bare Acts, http://www.helplinelaw.com/bareact/index.php?dsp=anc-monu-pre, accessed November 2, 2006. Also confirmed by Martin Pickford, interview by author, Nairobi, Kenya, October 12, 2002.

6. Gazette (1934), 249.

7. Biography Resource Center, "Louis Leakey," http://www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC, accessed October 2, 2002 (subscription service).

8. The Preservation of Objects of Archaeological and Paleontological Interest Ordinance, Laws of Kenya (1962), Ch. 215.11.1.

9. The Antiquities and Monuments Act, Laws of Kenya (rev. 1984), Ch. 215.

10. George Abungu, interview by author, Nairobi, December 3, 2002.

11. The National Museums and Heritage Act of 2006, Kenya Gazette, Supplement No. 63 (Acts No. 6), 123.

12. World Bank, "GNI per capita 2005, Atlas method and PPP," http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf, accessed November 1, 2006.

13. Kenya Subsidiary Legislation, 1991, The Lamu County Council (Lamu Old Town Conservation) Bylaws (1991), Legal Notice No. 292.

14. Ahmed Yassin, interview by author, Nairobi, November 28, 2002.

15. Compare the text for Lamu: "the Lamu County Council makes the following By-Laws" to that for Mombasa: "the Minister for Local Government makes the following order."

16. Yassin, interview; Jimbi Katana, interview by author, Mombasa, Kenya, January 23, 2003.

17. Kalendar Khan, interview by author, Mombasa, Kenya, November 22, 2002.

18. The Monument and Sites Department is under the direction of Dr. Mzalendo Kibunjia, a Rutgers-educated archeologist.

19. Khan, interview.

20. Gazette (1929), 507.

21. Pickford, interview; Laws of Kenya (rev. 1962), Objects and Areas of Land Declared to be Monuments, Cap. 215, Subsidiary Legislation. Between 1948 and 1970 the Kenyan National Park Service played a role in coastal sites since it had expertise operating public areas. During this period Fort Jesus and Gedi, for example, were degazetted and operated as parks.

22. Pickford, interview.

23.National Museums of Kenya, Sites and Monuments Department, Inland and Coastal Monuments (unpublished typescript, n.d.).

24. The current list stands at 223. George Abungu currently serves as Kenya's representative to UNESCO.

25. Waziri Sudi, Kalendar Khan, and Wycliffe Oloo are among those individuals who studied architecture and then joined the Museums' staff.

26. Athman Lali Omar, Kalendar Khan, Jimbi Katana, and Waziri Sudi are among Kenya's preservation leaders today.

27. Daily Nation (Nairobi, Kenya), October 21, 1982.

28. Athman Lali Omar, interview by author, Mombasa, November 14, 2002.

29. Zachary Otieno, interview by author, Nairobi, November 8, 2002. The property was gazetted in 1997, then degazetted and regazetted on the same day with new boundaries in 1998.

30. The case is still in court. Katana, interview; National Museums of Kenya Board of Governors v. Commissioner of Lands, Municipal Council of Mombasa, AIKO investments, and Habib Bank AG Zurich, HCCC No. 357 (1997).

31. The judge granted the injunction. The case remains in court. Katana, interview; National Museums of Kenya v. Commissioner of Lands, Municipal Council of Mombasa, and Kamlesh & Hitech Lalitchandra Pandya, HCCC No. 244 (2000).

32. Francis K. Mugambi v. Lamu Planning Commission, SRMCC No. 48 (1999).

33. George Abungu, interview by author, Nairobi, November 4, 2002.

34. Ibid.

35. Khan, interview.

36. P.M. Rukenya, Nairobi, to P.S., Ministry of Home Affairs, Nairobi, April 4, 2001; P.M. Rukenya, interview by author, Nairobi, October 4, 2002.

37. Farouk Adam, Nairobi, to Minister of Home Affairs, Nairobi, April 9, 2001.

38. Tove Hussein, interview by author, Nairobi, November 11, 2002.

39. Jane Kyaka, Nairobi, to R. W. Ngondo, Nairobi, August 20, 2001; Mzalendo Kibunjia, interview by author, Nairobi, September 25, 2002.

40. Stewart Henderson, Nairobi, to Minister for Home Affairs, Nairobi, April 2, 2001; Stewart Henderson, interview by author, Nairobi, October 2, 2002.

41. Les Gibson, Nairobi, to Minister of Home Affairs, Nairobi, April 4, 2001; Lalit Kana, Nairobi, to Minister of Home Affairs, Nairobi, March 9, 2001.

42. Steve Wambugu, Nairobi, to Minister of Home Affairs, Nairobi, April 6, 2001.

43. S.N. Mukunya, Nyeri, to P.S., Ministry of Home Affairs, Nairobi, April 5, 2001.

44. The Antiquities and Monuments Act, V/23.

45. Kibunjia, interview.

46. Gibson, interview.

47. H.A. Hebatullah, Nairobi, to Director General, National Museums, Nairobi, March 29, 2001.

48. The Antiquities and Monuments Act, V/20/a, V/21/3/a.

49. The Antiquities and Monuments Act, V/21/4.

50. "Monuments Declaration (Gazettement)," East African Standard (Nairobi), September 3, 2001.

51. Ibid.

52. Mzalendo Kibunjia, interview by author, Nairobi, November 4, 2002.

53. The most successful such incentive in the American experience has been a federal income tax credit for a percentage of an investment that rehabilitates a historic building used for commercial purposes. The private sector's response to the introduction of these tax incentives in 1976 exceeded the expectations of the preservation community. Several U.S. states have implemented their own historic preservation tax incentive programs. John M. Fowler, "The Federal Government as Standard Bearer," in The American Mosaic: Preserving a Nation's Heritage, eds. Robert E. Stipe and Antoinette J. Lee (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1997), 66.

54. Robert E. Stipe, "Historic Preservation: The Process and the Actors," in The American Mosaic, 5.

55. The American Antiquities Act of 1906 established protections for sites of historic and scientific interest on federal lands. See David Harmon, Francis P. McManamon, and Dwight T. Picaithley, eds., The Antiquities Act: A Century of American Archaeology, Historic Preservation, and Nature Conservation (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2006); also Richard Waldbauer and Sherry Hutt, "The Antiquities Act of 1906 at Its Centennial," CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship 3 no. 1 (winter 2006): 36-48.

56. Currently, Kenya has only one example of a tax advantage for historic properties: the 50 percent reduction in local property tax rates for Old Town Mombasa. Easements with financial advantages exist in Kenyan environmental legislation, but they have not been put to preservation uses.