Research Report

Connecting the Past, Present, and Future at Sitka National Historical Park(1)

by Kristen Griffin

Located in coastal southeast Alaska, Sitka National Historical Park preserves a variety of cultural resources, including the site of the landmark 1804 Battle of Sitka between the Kiks.ádi Tlingit and Russian fur traders intent on expanding their colonization of the North Pacific. The outcome of the battle influenced Tlingit, Russian, and Alaska history, and the battle site remains ethnographically significant for the Tlingit people today. In 2005, the park established a partnership with the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center (MWAC) to conduct a four-year archeological inventory project.(2) The primary goal of the project is to provide information about the full range of sites and periods in the park's history, including locations associated with the 1804 Battle of Sitka.

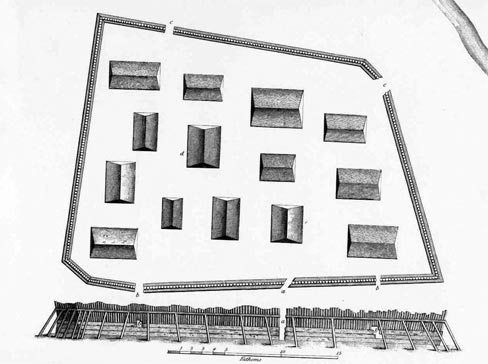

Of particular interest is the site of the Kiks.ádi clan's unique palisaded fort known as Shish'k'i Noow (Sappling Fort). Unlike typical Tlingit forts built on hilltops, Shish'k'i Noow was built on the flat peninsula at the mouth of the Indian River, where shallow tidelands kept Russian ships offshore. The use of flexible saplings in the fort's palisade resulted in walls capable of deflecting cannon fire.(3) It was from this fort that the Tlingit, led by warrior K'alyaan, prepared for an attack by Russian ships under the command of Alexander Baranov, chief manager of the Russian American Company.(Figure 1)

So far, an experienced team of MWAC archeologists skilled in remote sensing and battlefield archeology has successfully completed two field seasons at the site, including the recovery of cannon balls, a musket ball, and grape shot that appear to confirm the location of Shish'k'i Noow.(Figure 2) With the project at the halfway point, it seems appropriate to look at some of the ways the contemporary Tlingit community has influenced Sitka's archeological project, and what this involvement has meant for a park attempting to conduct a high profile archeological inventory of a complex, highly sensitive cultural landscape.

|

Figure 2. Metal detecting crew members Chris Adams and Charles Haecker survey the clearing known as the Shish'k'i Noow (Sappling Fort) site. (Courtesy of Bill Hunt.) |

Understanding Tlingit History and Culture

Located at the northern end of the Northwest Coast culture area, the Tlingit are known for their way of life closely attuned to the land and resources of the North Pacific. Their cultural foundation is a complex social system based on two parallel lineages, Raven and Eagle-Wolf. When the Russians established their first settlement near Sitka in the late 18th century, they encountered Tlingit people with a strong connection to the land. This connection is still apparent throughout the contemporary community in lively efforts to perpetuate Tlingit language, ceremonies, traditional knowledge, art, dancing, and reliance on htraditional foods.

Although all Native Alaskan cultural groups fought Russian colonization, the Tlingit are most often recognized as the people the Russians never subdued. The 1804 Battle of Sitka was a watershed event in Tlingit history. The loss of life makes the fort and battle site an extremely sensitive cultural landscape. For years, the story of the battle had been told within the narrow historical context of colonial settlement, in which the Russians defeated the Tlingit and went on to establish their colony at Sitka. Recently, that story has been expanded to include Tlingit oral history of the battle's aftermath and the withdrawal of the surviving Tlingit from the fort to a distant village, known today as the Survival March.

Shaping the Archeological Survey

Like all archeological projects, Sitka's archeological inventory draws on existing work, including an important excavation by Frederick Hadleigh West in 1958, a number of historical and collections research projects, a remote sensing survey, a geomorphological survey, an ethnographic study of Tlingit traditional use of the park, and the gathering of Tlingit traditional knowledge shared by elders.(4) An analysis of these sources helped determine the survey objectives and guided the MWAC archeologists in formulating the project research design.

In the same way, the project also draws on the insights gained from a series of community events in the recent past that enhanced public understanding of Tlingit history and important Tlingit cultural values. Three examples are the raising of a traditional totem pole, the repatriation of two highly significant cultural objects, and a ceremonial feast, or potlatch.

The totem pole raising took place in 1999 when, after years of planning, the Kiks.ádi clan commissioned a traditional totem pole for the approximate site of the former Tlingit fort.(Figure 3) The pole's design honors K'alyaan, the legendary warrior who led Tlingit forces in the 1804 battle. Prominent at the bottom of the pole is the distinctive Raven war helmet worn by K'alyaan. Although modern research and interpretation broadened the story of the Battle of Sitka, there was still very little to mark the Tlingit history physically in the park. As the pole was pulled into place, its presence restored balance by acknowledging the story of K'alyaan and all those impacted by the battle.

|

Figure 3. The Sitka community gathered to help the Kiks.ádi clan raise the K'alyaan pole at Sitka National Historical Park in 1999. (Courtesy of Sitka National Historical Park.) |

The second example involves two cultural objects tied to Russian-Tlingit conflict and repatriated to Sitka clans through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA): an iron Russian blacksmith's hammerhead and a distinctive brass ceremonial hat. Historical accounts indicate that the hammer, known to the Tlingit as K'alyaan aayi tákl', was captured by the Kiks.ádi in 1802 during their attack on the first Russian fort at Old Sitka and later used by K'alyaan at the 1804 battle. The hammer was repatriated to the clan in 2003 from the Sitka National Historical Park collection.

The brass hat, known as the Peace Hat, was forged by the Russians in the shape of a traditional woven crest hat. Museum records leave room for different interpretations of the hat's age, but indicated that the hat was commissioned by Baranov and presented to a Kiks.ádi leader sometime after the battle to foster peace between the Tlingit and Russians. The hat was repatriated to the clan from the American Museum of Natural History in 2004.

Both the Peace Hat and K'alyaan's hammer are clan at.óow, meaning they are important clan property that embody clan history and identity. Since their repatriation, the clan has entrusted them to the care of the park. Today, the Peace Hat and hammer occasionally join other at.óow in important ceremonies. Their presence serves as an unwritten but powerful reminder of the Tlingit history of the battle and subsequent peacemaking.(Figure 4)

The third example of an event that influenced the archeological inventory took place in October 2004 as the Kiks.ádi clan invited other Tlingit clans to gather at Sitka for a two-day ceremony to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Battle of 1804. The first day of the ceremony acknowledged those who had suffered loss as a result of the battle and provided the means to release their grief. The grief ceremony was followed by a koo.éex, or potlatch, devoted to the spirit of peace and reconciliation.(5)

In the interest of balance and respect, the clan felt it was necessary to invite someone to represent the Russian side of the conflict. With the assistance of historians from the Library of Congress, the clan was able to invite a direct descendant of Alexander Baranov, a central figure in the battle and Russian colonization of Alaska. Irina Afrosina, who traces her family through Baranov's second wife, a Native woman from Kodiak, accepted the clan's invitation. One of the most powerful moments in the program came as the modern day descendants of both K'alyaan and Baranov respectfully greeted each other and acknowledged their shared history in the company of K'alyaan's famous Raven helmet and hammer and the brass ceremonial hat that Baranov once offered to the Kiks.ádi in peace.

For park managers, these very different events in the years leading up to the archeological inventory shaped decision making about the project in a number of ways. Perhaps most importantly, they successfully conveyed the strong cultural connections that the Kiks.ádi and other Tlingit clans have to the park, and the depth of emotion that still surrounds the battle. They also offered a way to deepen the understanding of a complex history, including the human costs of the battle, and the changes that colonization brought to the Tlingit people.

In another sense, they offered subtle opportunities to learn about Tlingit cultural values by observing the care people took to be respectful, honor tradition, and maintain balance. These related perfectly to the Tlingit concept of Haa Shagoon, which acknowledges the ways that cultural traditions, passed down from ancestor to descendant, connect the past, present, and future.

Fostering Communication and Partnerships

On a practical level, these observations translated into a strong commitment by the park and project managers to maintain good communication with the public, the Tlingit community, and especially the Kiks.ádi clan. In the project's early phases, formal meetings with both the tribal government and the Kiks.ádi clan focused on basic information about the project, its objectives, and the practice of archeology. Recognizing that there was more than one tribal perspective on the project, the project managers invited the Sitka Tribe of Alaska (the local federally recognized tribal entity) and the Kiks.ádi clan (the clan with the strongest tie to the land within the park and the battle story) to appoint a liaison to the project. These individuals helped ensure that there was always a direct and open line of communication for voicing concerns, offering perspectives, or correcting misinformation. The liaisons were especially helpful since the practical season for fieldwork overlaps the time of year when many people in Sitka are fishing or involved in other subsistence activities away from home.

The archeologists from MWAC have been key participants in this communication partnership, welcoming public contact and working with the park to support public interest. So far, these efforts have included on-site visits, public meetings, and radio and newspaper interviews. MWAC also has up-to-date information about the project on its website, which has proven to be an excellent way for the public to keep up with the project. The MWAC staff also worked to learn about the Sitka community and maintained contact with tribal and clan representatives. MWAC also made a commitment to invite participation by Tlingit clan members in the fieldwork. So far five Tlingit individuals, all young people, have worked on the project.

The park designated a staff person to handle project communications, respond to media and information requests, and share information with other park staff. Park interpretive rangers have been able to carry the project's messages of cultural sensitivity and resource protection directly to visitors. Regular press releases, public meetings, and newsletters have helped keep the public informed. The park has developed a popular archeology education program for students and teachers that showcases some archeological techniques in the classroom, followed by field trips to the park to view archeological collections, tour the survey area, and meet the archeologists.

Cultural events hosted by Sitka's active Tlingit community conveyed important cultural values and concerns to park and project managers. Park staff learned the importance of "hearing," or perhaps more accurately "feeling," community views that could impact a cultural resource project. With two field seasons remaining, the Midwest Archeological Center's archeological inventory of Sitka National Historical Park has already generated important new information about the park and its history. Also important are the ways the project is helping build a partnership grounded in communication and a mutual respect for Tlingit cultural values.

About the Author

Kristen Griffin is an archeologist and park historian at Sitka National Historical Park in Sitka, Alaska.

Notes

1. The author wishes to say gunalcheesh (thank you) to Gene Griffin, Lisa Matlock, and Greg Dudgeon at Sitka National Historical Park; Steve Johnson Jr., archeology project cultural liaison for the Sitka Tribe of Alaska; and Wayne Howell at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve for offering comments on this report.

2. The project was funded by the National Park Service's Systemwide Archeological Inventory Program (SAIP) and the Cultural Resources Preservation Program (CRPP).

3. For more information on the battle, see Richard Dauenhauer and Lydia Black, eds., Anooshi Lingit Aani Kaa/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804 (Seattle: University of Washington Press and Sealaska Heritage Institute, 2007). This forthcoming book will include an essay describing the research history of the fort site.

4. The MWAC webpage features information and photographs about the project at http://www.nps.gov/mwac/.

5. This ceremony was unique in that a traditional koo.éex would not be divided into two separate ceremonies.