Landscape of CultureCongaree National Park, like the Congaree River, is named for the Congaree people who once lived in this region. Unfortunately, not much is known about the Congaree as a significant number of their population is thought to have died in the 17th and 18th centuries, likely due to warfare and disease brought on by European colonization. Over time remaining Congaree would have been absorbed into neighboring tribes.Congaree National Park not only protects the nation's largest remaining tract of southern old-growth bottomland forest in the United States, it also preserves a landscape shaped by the many people who have lived in and used the floodplain for thousands of years. Whether residents or visitors, positive or negative, humans have left their mark on this land and helped to make it what it is today. As we pass by some of those massive trees in floodplain, we have to wonder, what have they seen during the span of their lives?

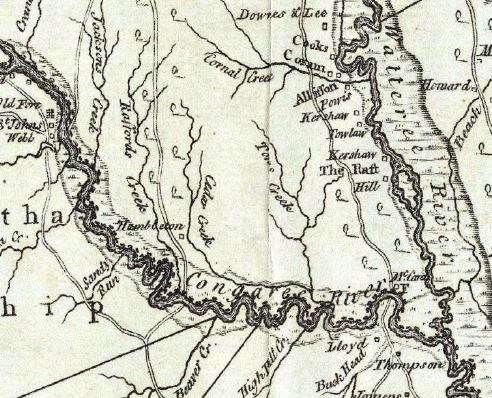

Earliest ResidentsArchaeological evidence suggests humans have inhabited this area for at least 10,000 years. These earliest people were nomads, living in temporary camps while following the large mammals they relied upon for food and gathering whatever else they needed. Over time these nomadic groups formed small tribes, built more permanent villages, and experimented with crops and pottery. The introduction of corn, beans, and squash led to the eventual unification of these many small tribes into large chiefdoms with large territories. It was these people that met the Spanish led by Hernando de Soto in April of 1541. Wilderness ExplorersThe Spanish stay was short, but it had lasting impacts. European diseases devastated native populations, and hogs brought as food remain even today. The English colonists who established Charles Towne in 1670 intended to stay, and slowly moved inland as more colonists arrived. In 1701, English surveyor John Lawson traveled up the Santee to the confluence of the Wateree and Congaree rivers. There he encountered the inhabitants who lived there, the remnants of the once great chiefdoms who met de Soto:

Colonization of the LandBy the mid 1700's, news of rich farm land brought more settlers seeking wealth to the "Congarees," the land found between the Congaree and Wateree rivers. Much of the Congaree floodplain was granted to or claimed by planters whose intent was to plant cash crops such as rice and indigo and make their fortune. These settlers brought more changes to this landscape. Plantations were built, new roads soon crossed the area, and ferries like McCord's Ferry (later renamed Bates Ferry) transported goods across the Congaree River to the coast. Land was cleared and dikes were built in the floodplain to try and control the regular flooding. But while many tried, few had any success in truly taming this wilderness.

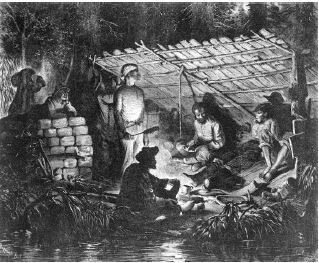

A Refuge from SlaveryFor enslaved people seeking freedom from the oppressive plantation economy, this jungle-like wilderness served as a refuge. While a few made the long journey north, many instead ran to the woods to find freedom while remaining near family and supplies. Called maroons, these men and women made the decision to live a rough life, sometimes for years, in the wilderness rather than be subject to the cruelty of slavery. Facing threats from both slave catchers and the unpredictability of nature, they chose to resist their enslavers and live as free people in the wilderness, determining their own future rather than having it determined for them.

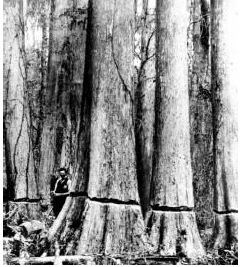

Champions Begin to FallThe rapid industrialization of the United States after the Civil War required resources to fuel and build a swiftly expanding nation. The need for lumber was no exception. Francis Beidler of Chicago purchased 15,000 acres of the Congaree floodplain to harvest the stands of immense old-growth cypress trees. Over almost 20 years, loggers cut many of these massive trees, floating them downstream to his lumber mill to become shingles, pilings, or house siding. However, getting these trees out was difficult and costly, and by 1917, logging operations had ceased, offering this landscape a reprieve. But the danger that more giants might fall to the axe was far from over.

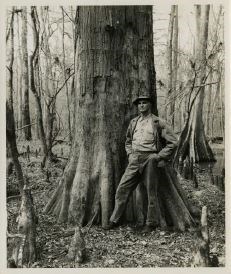

The Last of Its KindThough no longer logging the land, the Beidlers held onto it with the hopes that one day they could again log it. In the meantime, they leased sections of land out to local hunt clubs to use for recreation. A member of one of those hunt clubs, local newspaper editor Harry Hampton spent his time exploring the Congaree floodplain. He came to the realization that this was a unique place, the last of its kind and size, and worthy of saving. Through his newspaper columns he advocated for the preservation of the Congaree so that future generations could enjoy it as he did. He talked to whoever would listen and worked tirelessly to help save the forest he loved from disappearing forever.

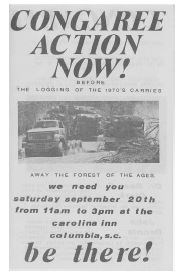

Congaree Action NowBy the end of the 1960's, logging once more threatened to topple the giants of Congaree. Though Harry Hampton had tried, his efforts to preserve this forest of champions had been frustrated. But the 1970's saw a new generation of advocates rise up. Calling for "Congaree Action Now," activists from South Carolina and from across the country lobbied Congress to make Congaree a national park. Through their tireless efforts, they convinced the landowners to sell the land and Congress to establish Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976. This promised to preserve the land for future generations to experience and enjoy in its natural condition. Congaree TodayRedesignated as a national park in 2003, Congaree today encompasses over 26,000 acres of bottomland and upland forest in the Midlands of South Carolina. As a federally designated Wilderness Area, Important Bird Area, International Biosphere Reserve, and a RAMSAR Wetland of International Importance, Congaree not only plays an important ecological role, but it serves as a reminder of what our nation used to look like prior to the arrival of Europeans explorers and colonists. As a national park people will forever be a part of Congaree, remaining a significant part of this dynamic landscape. |

Last updated: January 7, 2026