NPS Photo - A common black and white morph of the California Kingsnake.

NPS Photo – A closeup of a brown and cream morph of the California Kingsnake.

Photo courtesy of Gary Nafis on Californiaherps.com – This oddly patterned (aberrant morph) kingsnake sports white longitudinal stripes that break up into dashes.

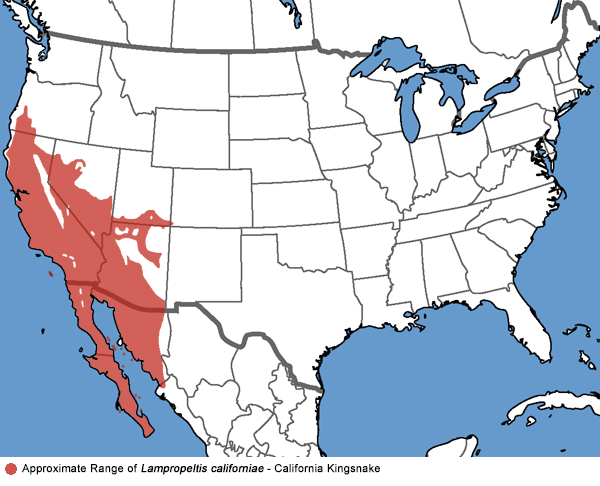

California Kingsnakes can be found in a large variety of habitats throughout most of California and much of the southwest, including Baja California, Mexico. One of the reasons for this wide distribution is their ability to eat a variety of prey – these powerful constrictors dine upon small mammals, lizards, amphibians (frogs and salamanders), birds, and even large invertebrates, such as insects. Their most remarkable type of prey, however, is other snakes! California Kingsnakes are “kings” because they hunt and devour various snake species, including other kingsnakes and even rattlesnakes – they are immune to rattlesnake venom!

Map courtesy of California Herps – An approximate range map for the California Kingsnake.

NPS Photo/McKenna Pace - Our Resident California Kingsnake, Boros, positioning himself to devour a rat whole.

Photo courtesy of Jerry Schudda on focusingonwildlife.com – A kingsnake eating the back end of a Diamond-back Rattlesnake. Eventually the entire rattlesnake will be swallowed whole.

Every Thursday afternoon our Science Education Department brings out one of our four resident snakes for a snake “meet and greet”: two of these snakes are California Kingsnakes. A frequent question from visitors is if rattlesnake antivenom was developed by studying California Kingsnakes. The short answer is no – antivenom is traditionally created by milking (harvesting) venom from a spider, snake, or insect. A small amount of the gathered toxin is then injected into domestic animals such as horses, goats, or cattle. This non-lethal amount of venom triggers an autoimmune response from the mammal, releasing antibodies which are then harvested, purified, and made into an antivenom serum.

NPS Photo/Nicole Ornelas – Volunteer Isabella features Summer, one of our resident California Kingsnakes, during a snake meet-and-greet.

Though California Kingsnakes are not directly involved in the synthesis of antivenom, they are a subject of research for venom immunity in general – this species has helped scientists understand how venom works, which is invaluable for the treatment of rattlesnake bites. So, if you’re lucky enough to spot a California Kingsnake, be sure to thank him (or her) for eating all the pests that destroy your yard, for keeping dangerous snakes at bay, and for furthering our understanding of venomous snake bites!

References

Herptiles at Cabrillo National Monument:

https://www.nps.gov/cabr/learn/nature/reptiles-and-amphibians.htm

More About California Kingsnakes:

http://www.californiaherps.com/snakes/pages/l.californiae.html

More About Kingsnakes in General:

https://www.livescience.com/53890-kingsnake.html

More About Venom and Antivenom:

https://www.nps.gov/cabr/blogs/venomous-versus-poisonous-same-thing-right-wrong.htm

https://www.si.edu/spotlight/antibody-initiative/antivenom