NPS Photo – the iconic flat hat that completes the National Park Service Ranger uniform.

NPS Photo – the iconic flat hat that completes the National Park Service Ranger uniform.It all starts with an area of natural hot springs in central Arkansas. Recognizing their natural beauty and recreational importance to both locals and tourists alike, Congress established the area as Hot Springs Reservation in 1832. This designation outlawed activities such as bathing in the pools or mining the minerals around them. Though the National Park Service had not been established yet (that wouldn’t come until 1916), this was the first time the federal government set aside an area of land for preservation purposes – the first unofficial national park, if you will. However, the government made these rules without hiring anyone to actually enforce them. People could probably still get away with bathing in the pools.

NPS Photo/Hot Springs National Park – the Thermal Pools of Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas.

NPS Photo/Hot Springs National Park – the Thermal Pools of Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas.A similar story unfolded in the Yosemite Valley and Yellowstone. In an effort championed by naturalist John Muir, the Yosemite Valley was set aside by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864 and given as a public trust to the state of California. Again, there was no formal body to enforce the rules – no taking, no hunting, no uncontrolled fires, etc. It wasn’t until Congress designated Yellowstone as the nation’s first official National Park in 1872 that the government finally realized that they needed someone to oversee the park. The job of protecting Yellowstone National Park was given to a man named Nathaniel Langford, the National Park Service’s first Superintendent. This one man’s task was to patrol the entire area of Yellowstone National Park – a job he was given no money or other resources to complete.

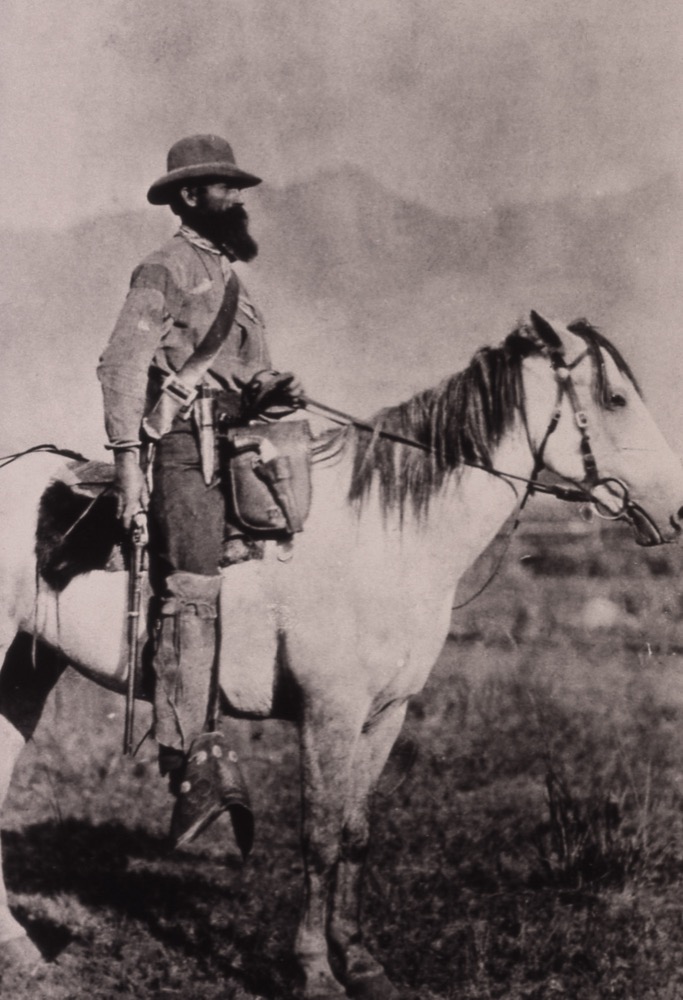

NPS Photo/Yellowstone National Park – the first park Superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, on horseback in Yellowstone National Park, 1872.

NPS Photo/Yellowstone National Park – the first park Superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, on horseback in Yellowstone National Park, 1872.As America continued to expand west, the need to protect the nation’s beautifully rich cultural and natural resources grew. More and more areas, including what is now Sequoia, King’s Canyon, and Glacier National Parks, were being protected by acts of Congress. As a consequence, the need for park employees also grew. During the 1880s, control of the National Parks was given to the United States Army; they were cheap, took orders well, and had at least a little bit of training. In fact, today’s Park Ranger uniform, complete with the flat hat, is derived from these early military uniforms. However, the Army didn’t have any real legal authority to write tickets or arrest anyone who broke the law. Plus, they couldn’t satisfy the visitors who were there to gain knowledge. Still, the Army was better than nothing.

NPS Photo/Yosemite National Park - About forty members of U.S. 6th Cavalry, Troop F, shown mounted on, or standing beside their horses, and lined up atop and beside the Fallen Monarch tree in the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, Yosemite National Park, 1899.

NPS Photo/Yosemite National Park - About forty members of U.S. 6th Cavalry, Troop F, shown mounted on, or standing beside their horses, and lined up atop and beside the Fallen Monarch tree in the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, Yosemite National Park, 1899.Finally, with the passage of the Organic Act by Woodrow Wilson in 1916, we have the creation of the National Park Service, a federal bureau under the Department of Interior tasked with managing the nation’s public lands. At the time, there were 14 Parks and 21 Monuments (including Cabrillo) spread across the country. Fast forward to the passage of the New Deal in 1933, which brought with it a massive expansion of National Park Service land and employees. The number of NPS sites doubled, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) program gave jobs to thousands of men and women to build roads, construct trails, and greet visitors at National Parks across the country. The National Park Service saw another massive expansion during the Mission 66 era, when, funded by Congress, visitor’s centers, signs, facilities, and more were constructed in parks across the country with the hopes of drawing in more visitors.

NPS Photo/Grand Teton National Park – men lined up to salute the flag after a day’s work at Jenny Lake CCC Camp in Grand Teton National Park, 1936.

The need for law enforcement at National Park units has clearly always existed. The National Park Service’s mission is “to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations,” but therein lies an inherent contradiction – how do we preserve these resources while still allowing the public to use and enjoy them?

This contradictory idea really came to light during the summer of 1970. Yosemite Valley had become a place for people far and wide to congregate, often in massive numbers, and this was a time fueled by narcotics and “free-spirit” ideals. The Rangers at Yosemite didn’t know how to handle it, so they increased camping fees and issued warnings and citations, but the crowds didn’t leave. The issue soon became political. Besides, the park exists for the people, right? While it is still a little unclear how the day unfolded, July 4, 1970 became a day now known as the Stoneman Meadow Riots. This event changed the way the National Park Service manages people and resources and gave birth to the modern era of park law enforcement we are familiar with today.

NPS Photo/Alex Warneke – Law Enforcement Rangers play an integral role in preserving and protecting the resources at Cabrillo National Monument, and keeping the public safe, too.

NPS Photo/Alex Warneke – Law Enforcement Rangers play an integral role in preserving and protecting the resources at Cabrillo National Monument, and keeping the public safe, too.Today, under the General Authorities Act of 1976, Law Enforcement Rangers are given the authority to issue citations and arrest those who break the law within National Park Service boundaries. Unlike the Army days of the 1800s, consequences for criminals go beyond simple banishment from the park. Like all other types of Rangers and other employees of our nation’s National Parks, however, their ultimate goal is to promote stewardship among visitors. After all, these parks are not only for the people of today, but for our children of tomorrow, as well.

So, who are these Law Enforcement people? Are they Rangers? Are they cops? Bonnie Phillips likes to say, “we’re something more than both of those.”

NPS Photo/Nicole Ornelas – Ranger Bonnie Phillips speaks to Naturally Speaking attendees on November 17.

NPS Photo/Nicole Ornelas – Ranger Bonnie Phillips speaks to Naturally Speaking attendees on November 17.*A special thank-you to Ranger Bonnie Phillips for her captivating lecture on November 17. Future Naturally Speaking lectures will be open exclusively for Cabrillo Volunteers and Foundation members. If you would like to become a Foundation member and attend future members-only events, visit the CNMF website at: https://cnmf.org/shop/membership/

**Our next Naturally Speaking lecture, entitled How to Spot a Whale: Gray Whales and Other Marine Mammals of Point Loma, features Dr. Thomas Jefferson. This lecture will specifically highlight Gray Whales and how we can spot them as they migrate south from Alaska to Baja California, Mexico this winter. The event will be held January 17 at 6 pm in the Cabrillo National Monument Auditorium. RSVP to this CNMF members-only event here: https://cnmf.org/event/how-to-spot-a-whale-gray-whales-and-other-marine-mammals-of-point-loma/