Repeat photography, in which a historic photo is compared to a modern retake, is a tool that can help us understand ecological changes and what may have caused them, especially when used alongside other types of data, such as the study of tree ring patterns (dendrochronology), grains of dust and pollen (palynology) and artifacts and writings on the history of human use.

Although change is part of nature, here on the Pajarito Plateau at the edge of the Jemez Mountains, we have seen major changes to our environment due to human influence during the past 100-150 years. In the early 1990s, Craig Allen and John Hogan, ecologists and scholars of this landscape, had the idea that a direct visual comparison of our landscape now and long ago by repeat photography might prove insightful. They began a search that took them to numerous libraries, universities, and even the National Photographic Archives near Washington D.C. for the earliest photos they could find of Bandelier National Monument and the Jemez Mountains.

Their search yielded over 300 historic photos that looked repeatable. Most of these early photos were focused on archeological finds, geology, railroad surveys, and advertising – certainly not on long-term landscape changes! However, this proved advantageous in that the original photographers were not biased. That is, they did not seek out locations they thought might change in the future; they were simply snapping photographs of stone walls or steep canyons laced with history.

In 1995, Allen and Hogan began to retake these historic photos, often pinpointing their locations with the help of local expertise. They meticulously lined up their camera to the historic photos and recorded a GPS point, azimuth, and other conditions for each photo. To date, they have retaken close to 100 photos. The earliest photos found so far are from the year 1880 when Adolph Bandelier, for whom the monument is named, came exploring in Frijoles Canyon.

Each pair of photos was analyzed for landscape changes, keeping in mind that natural events coupled with human disturbances can impart unexpected and swift consequences for ecosystems. Here are a few examples of photo pairs that held interesting clues to the past.

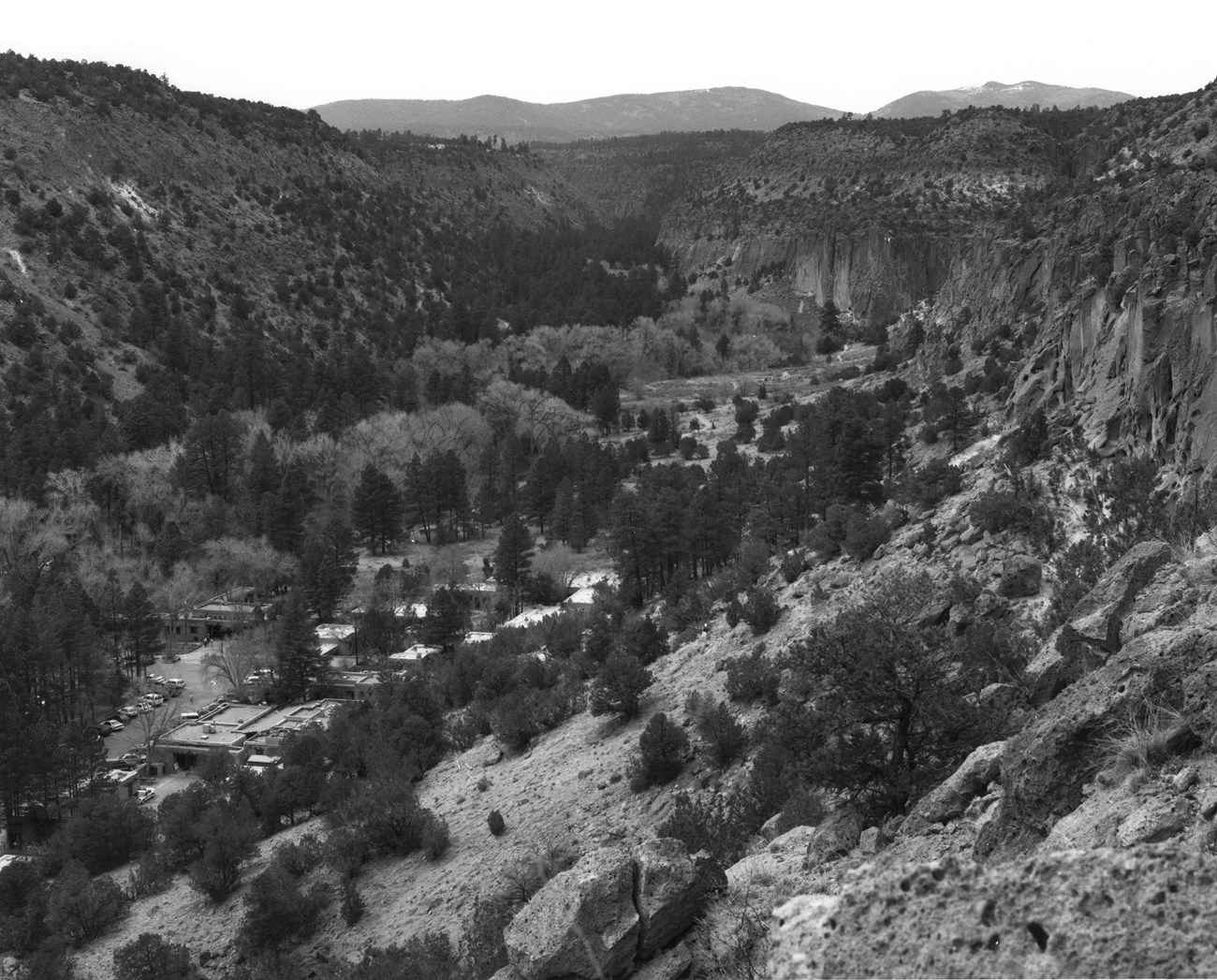

Frijoles Canyon

This pair of photographs showcases the main visitor use area of Bandelier National Monument - Frijoles Canyon. Perhaps the most striking difference in Frijoles Canyon between 1920 and 1999 is the floodplain. Where riparian vegetation thrives today, agricultural fields covered the canyon bottom in the monument's early days. There were orchards, barns, fences, irrigation ditches, and crops used by those who inhabited the canyon at that time. A marked increase in the density and height of riparian trees in the last century suggests that many trees were harvested for wood as well. Today, the evidences of these historical uses are but subtle remnants in the form of old ditch scars and a few scraggly fruit trees.

Now it's time to grab your magnifying glass! A very careful examination of the two photos reveal hard to see, yet drastic changes on the mesas. The piñon-juniper woodland, a dominant vegetation type in the Pajarito Plateau, covers the mesa sides and tops in the modern photo. However, ponderosa pine forests, characteristic of higher elevations than piñon-juniper woodlands, dominate the mesa tops and occur on the sides in the 1920 photo (most visible on the leftmost mesa top). The rapid upslope migration of ponderosa forest and subsequent colonization by piñon-juniper woodland over the last century has been a widespread phenomenon in the Jemez Mountains.

What caused this shift? Prior to the late 1800s, continuous ground cover carried low-intensity, frequent fires through the landscape. Beginning in the 1880s, large numbers of grazing livestock were introduced and ate the fire-carrying groundcover. Simultaneously, a century of active fire suppression had begun. Thus, the ponderosa and piñon-juniper habitats became fire-starved, growing denser and denser with woody growth and creating conditions for the easy spread of disease and hot fire through the trees. A severe drought during the 1950s stressed the ponderosa pines, paving the way for a bark beetle attack that killed them back and pushed the ecotone upslope by as much as 2 kilometers across the Jemez Mountains. And this retreat of ponderosa forests was not a one-time occurrence. Rather, this trend continues in the area due to long-term changes in climate toward warmer and potentially drier conditions.

Image by unknown photographer 1920

Image by unknown photographer 1920 Image by Steve Tharnstrom 1999

Image by Steve Tharnstrom 1999The Rio Grande

Looking north up the Rio Grande River from the mesa top near the mouth of Frijoles Canyon, some features like the scree slopes appear to have remained quite stable since 1920, while other areas have seen big changes. Since 1920, dams, levees, and diversion channels have been built, changing the flow of the river. Specifically, in the 1980s, flooding of unusually large proportions occurred in the floodpool of the Cochiti Reservoir. This killed most of the riparian plants, including rare species, on the banks of the river and buried natural springs in sediment. This barren area was then colonized by weedy plants such as cocklebur and saltcedar. Today, native cottonwoods and willows are trying their best to regain control in the riparian area. Still visible in the modern photo is the "bathtub ring" above the river made by the absence of riparian vegetation and a build-up of sediment as a reminder of the floods.

We have only begun to investigate the numerous collection of photo pairs, and already we have seen clearly illustrated evidence of large-scale ecological changes. Past management decisions have had noteworthy impacts on the forests and meadows of the Jemez Mountains. Today, better-informed management strategies will continue to be the key to ameliorating these impacts and ensuring the health and resilience of this landscape into the future. The gathering of important place-specific ecological data, including snapping plenty of 3x5s, will provide us with direct and powerful knowledge about how to better manage the Jemez Mountain landscape.

Image by unknown photographer 1920

Image by unknown photographer 1920 Image by Steve Tharnstrom 1997

Image by Steve Tharnstrom 1997Want to learn more?

Here is a link to the full report "The use of repeat photography for historical ecology research in the landscape of Bandelier National Monument and the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico" submitted by Craig Allen and John Hogan in 2000 to the Southwest Parks and Monuments Association.