Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Bayard Rustin.

Previous: Learning from Bayard Rustin

Article

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/97518848/

The content for this article was researched and written by Dr. Katherine Crawford-Lackey.

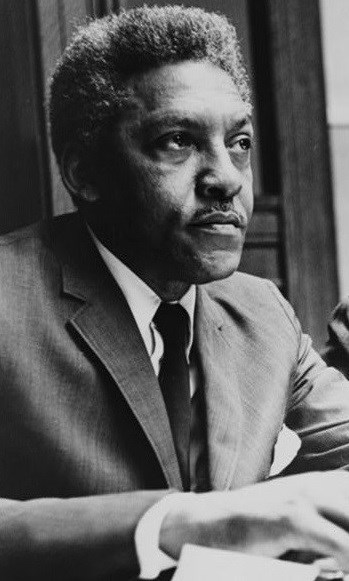

The struggle for Black civil rights is often associated with figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks. But Bayard Rustin organized some of the movement’s most iconic protests, including the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963).

Born in Pennsylvania in 1912, Rustin was raised by his maternal grandparents. His grandmother’s Quaker faith – rooted in peace, community, and equality – influenced his decision to become an activist. Even as a young man, Rustin fought for many causes, including racial equality and workers’ rights. Later in his life he also advocated for gay rights.

One of Rustin’s most notable contributions to the African American Civil Rights Movement was his planning of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Now popularly associated with Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, this march helped pave the way for the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Rustin also introduced the concept of nonviolence to the movement (influenced by the moral leadership of Mahatma Gandhi). King later adopted this strategy of nonviolence, making it the foundation of the movement.

Despite his leadership, Rustin was sidelined from the movement due to his sexual orientation. As a gay man, Rustin was largely kept out of the public eye. But without Rustin’s contributions, the Civil Rights Movement may not have been as successful.

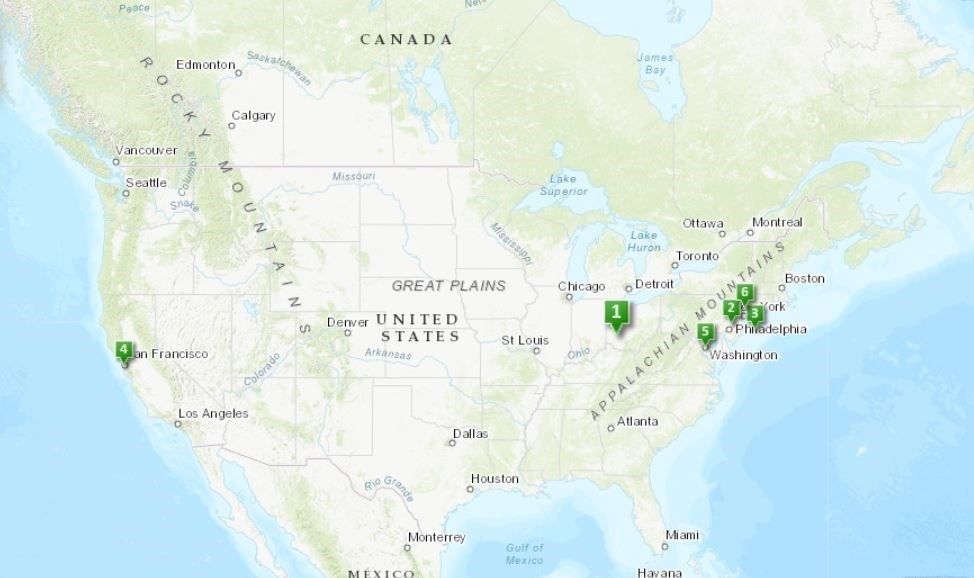

Discover the places where Rustin lived, worked, and studied and gain a better understanding of how he shaped social change in 20th century America.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/95507830/

In high school, Rustin was a popular student, excelling at track and football. He was also dedicated to social causes, including fighting against segregation. Attending the movies as a teen, he refused to sit in the segregated section of the cinema.

Rustin continued his activism in college at Wilberforce University in Ohio. Founded in 1856, the school was originally established to educate free and formerly enslaved African Americans. The university temporarily closed at the start of the Civil War. It was re-opened in 1863 when the African Methodist Episcopal Church purchased the property. Since then, Wilberforce University has operated as the nation's oldest, private Historically Black University.

Since its founding, Wilberforce has welcomed a number of famous figures. W.E.B. Du Bois and Charles Young both taught at the school. Du Bois was an early civil rights leader and one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Young also had a distinguished career. A notable military leader, he was one of the first African Americans to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Rustin attended the university in the fall of 1932 on a music scholarship (he was a talented singer). Wilberforce was the only college to have an African American Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). The university required all male students to participate in ROTC during their first two years, but Rustin felt that participating in ROTC went against his Quaker belief in pacifism.

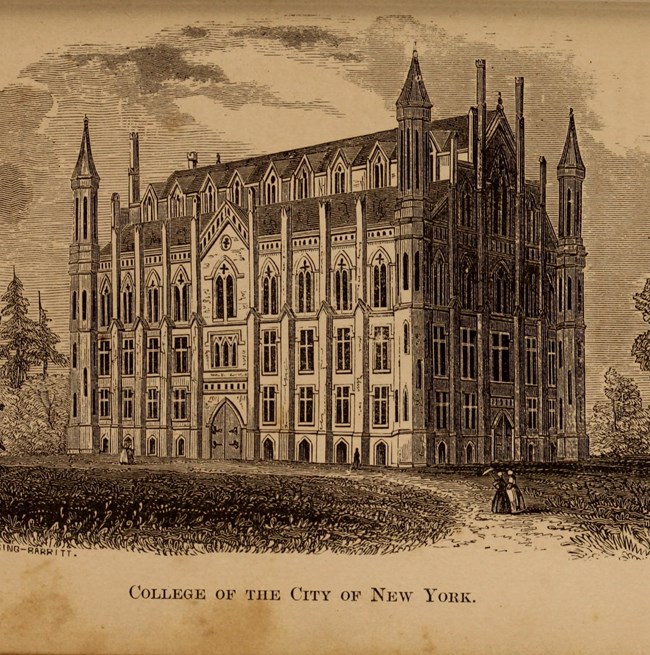

Rustin eventually lost his scholarship and left the university. The departure may have stemmed from Rustin’s dislike of his forced participation in ROTC. When interviewed towards the end of his life, Rustin explained that he was expelled for organizing a strike to protest the poor quality of food served by the cafeteria. Rustin continued his college education at Cheyney State Teachers College in Pennsylvania and eventually City College in New York City.

Wilberforce University is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1937, Rustin moved to the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. He enrolled at City College of New York where he became active in the Young Communists League because of its opposition to racial injustice. At the time, the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) was dedicated to advancing the rights of African Americans. When World War II broke out in 1939, the CPUSA abandoned its efforts to support Black Americans. Frustrated, Rustin left the party and began working with noted civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph. The two began planning a march on Washington in 1941 to protest racial segregation in the armed forces. Wanting to avoid such a public demonstration during wartime, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued the Fair Employment Act outlawing discrimination in defense industries. In return, Randolph and Rustin cancelled the march. But their work was far from over. Over two decades later, Rustin and Randolph would organize one of the most famous demonstrations in American history: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963).

City College’s North Campus Quadrangle where Rustin attended school is listed on in the National Register of Historic Places.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/gottlieb.08801/.

A few years after Rustin moved to New York, he was hired as a member of the chorus for a Broadway musical. While the musical itself was not well received by critics, Rustin had secured his reputation as a talented singer and actor. He joined a band, Josh White and the Carolinians, and recorded an album with Columbia Records. The band also frequently performed at Café Society in Greenwich Village.

While many places in New York City were segregated, Café Society welcomed a diverse group of performers and patrons. At this time, Greenwich Village was gaining a reputation as a progressive, artistic area of town. The neighborhood became a hub for writers and musicians including Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and Allen Ginsburg. Rustin met many like-minded people and was able to be more open about his sexuality.

Greenwich Village Historic District is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Photo by Dorothea Lange , U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17318582.

The Japanese YWCA in San Francisco was built by the Japanese American community. During World War II, Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens were forcibly incarcerated in camps across the country. When Japanese communities were forced to abandon their homes during the war, African Americans moved into these neighborhoods. San Francisco was no exception.

In the 1940s, public facilities were segregated. In many cities, white residents would not allow African Americans to use the same bathrooms, gyms, movie theatres, and more. The Japanese YWCA on Sutter Street was rented to the United Service Organization which used the building as a segregated recreational facility for African American troops.

In 1943, a chapter of the Committee on Racial Equality (CORE) was formed and based at the former YWCA building. To educate young people about racial discrimination, CORE invited Bayard Rustin to teach an intensive study course. The seven-week course was well attended by African American children from the community as well as white and Black soldiers based in the area.

The Japanese YWCA is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

CC0

Since its dedication in 1922, the Lincoln Memorial has been the site of many protests and demonstrations. In 1939, for example, singer Marian Anderson gave a concert on the steps of the memorial after being barred from Constitution Hall because of her race. It was also the focus of the August 28, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963).

In late 1961, Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph began planning a march on Washington. They wanted to bring attention to the economic inequalities and civil rights abuses against African Americans, Latinos, and other disenfranchised groups. Organizing a two-day protest that included a massive march, Rustin and Randolph hoped to end racial discrimination in the workplace.

As they organized the march, Randolph and Rustin approached other civil rights leaders for help. They contacted the heads of organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Dorothy Height, President of the National Council of Negro Women pointed out that African American women should also be involved in the planning process. She worked with Randolph, Rustin, and others to make sure women’s interests were represented.

Many influential figures spoke at the march, including John Lewis and Roy Wilkins. Martin Luther King, Jr., head of the SCLC, also gave a speech. On that hot August afternoon, he stood on the steps of the memorial and delivered what is now remembered as the “I Have A Dream” speech.

While the march is now largely associated with King, Rustin, Randolph were the key organizers. The march resulted in the passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964). This law banned segregation in public places and outlawed employment discrimination. Not only did this law protect people on the basis of race, it also banned discrimination on the basis of religion, sex and national origin.

The Lincoln Memorial is part of the National Mall and Memorial Parks, a unit of the National Park Service.

Photo by Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14542528

In 1962, Rustin purchased Apt. 9J of the newly built Penn South Complex in the West Chelsea section of Manhattan. The apartment had a living room, kitchen, bathroom, and two bedrooms. Rustin later installed a wall in the kitchen area to create a dining room.

At the time, Rustin was in the process of planning the upcoming Marching on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963). Even though the march was one of the highlights of Rustin’s career, he knew there was more work to be done. While he traveled all over the U.S. advocating for equal rights, he also spent time in his apartment planning and organizing protests and demonstrations.

In 1977, Rustin was walking the streets of New York City when he met Walter Naegle. The two felt an instant connection and quickly began dating. Naegle eventually moved into Rustin’s apartment where they lived together until 1987.

During the summer of 1987, Rustin and Naegle went to Haiti on a humanitarian mission. Shortly after returning to New York, Rustin fell ill with a perforated appendix. Doctors operated, but Rustin went into cardiac arrest shortly after. He passed away on August 24, 1987. After Rustin’s death, Naegle continued to reside in the apartment, preserving it almost exactly as it was while Rustin was alive.

Rustin resided at Apt. 9J at the Penn South Complex from 1962-1987, his longest place of residence. The apartment (and building) is significant for its association with his life and activism.

The Penn South Complex is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Learn more about the Bayard Rustin Residence.

Bibliography:

Brimner, Larry Dane. We are One: The Story of Bayard Rustin. Calkins Creek, 2007.

D'Emilio, John. Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. New York: Free Press, 2003.

“Bayard Rustin: Bibliography.” Stanford,The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/rustin-bayard

National Register nominations (available at the National Archives).

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Bayard Rustin.

Previous: Learning from Bayard Rustin

Last updated: February 19, 2025