Last updated: May 16, 2023

Article

From Canterbury to Little Rock: The Struggle for Educational Equality for African Americans (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Photo by and courtesy of Tod Swiecichowski)

On the southwest corner of the main crossroads in the town of Canterbury, Connecticut, stands a gracious house. Although it resembles many other houses in the area in appearance, this house stands apart because of the unique role it played in promoting the educational opportunities of African Americans prior to the Civil War. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1991, the house is open to the public as the Prudence Crandall Museum. It has changed little since events here in the early 1830s focused national attention on abolition and the rights of African Americans to a quality education.

At the intersection of 14th and Park Streets in Little Rock, Arkansas, stands a large high school. Although it may resemble other large urban high schools built in the 1920s, Central High School captured the attention of the nation in 1957, when nine African-American students attempted to integrate Little Rock's schools. In 1998, the building, already a National Historic Landmark, was designated as Central High School National Historic Site, a unit of the National Park System.

Canterbury, Connecticut, and Little Rock, Arkansas, are links in a chain of events representing the long struggle for equal educational opportunities for African Americans. This lesson plan highlights two important historic places and the role each played in testing the prevailing assumptions of the time regarding racial integration of schools. It also tells the story of conflict between the rule of law and the rule of the mob, and the importance of a free press in exposing social injustice.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Historic Landmark files, "Prudence Crandall House" (with photographs) and "Little Rock High School" (with photographs), as well as other sources related to these two historic properties. It was written by Kathleen Hunter, Director of Interpretation and Education at the Old State House, Hartford, Connecticut. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in American History courses in units on 19th-century reform movements (abolitionism), the civil rights movement, or the history of education in America. The lesson also could be used to enhance the study of African American history or women's history.

Time periods: 1830s and 1950s

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

From Canterbury to Little Rock: The Struggle for Educational Equality for African Americans relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 4A- The student understands the abolitionist movement.

- Standard 4B- The student understands how Americans strived to reform society and create a distinct culture.

Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Standard 4A- The student understands the "Second Reconstruction" and its advancement of civil rights.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

From Canterbury to Little Rock: The Struggle for Educational Equality for African Americans relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard A - The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

- Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

- Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

- Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

- Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

- Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

- Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

- Standard F - The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

- Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

- Standard A - The student examines persistent issues involving the rights, roles, and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

- Standard B - The student describes the purpose of government and how its powers are acquired, used, and justified.

- Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

- Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues - recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

- Standard D - The student practices forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

- Standard E - The student explains and analyzes various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

Objectives for students

1) To examine how Prudence Crandall challenged the prevailing attitude toward educating African Americans in New England prior to the Civil War.

2) To understand the court actions and public reactions involved in desegregating schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1950s.

3) To compare and contrast the events relating to African-American education that occurred in Canterbury, Connecticut, in the 1830s and Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1950s.

4) To investigate the history of public education in their own community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The map and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) a map showing the locations of Canterbury, Connecticut, and Little Rock, Arkansas;

2) two readings about important events that occurred in Canterbury and Little Rock;

3) seven photos of the Prudence Crandall Museum and Little Rock Central High School.

Visiting the sites

The Prudence Crandall Museum is located at the intersection of Routes 169 and 14 in Canterbury, Connecticut. It is open to the public from early February to mid-December, Wednesday-Sunday, 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Free admission is offered to school groups by appointment. The museum includes three period rooms, changing exhibitions on a variety of themes, and special seasonal events. For more information, contact the Prudence Crandall Museum, P.O. Box 58, Canterbury, Connecticut 06331.

Little Rock Central High School, now a unit of the National Park System, is located at the intersection of 14th and Park Streets. Permission to enter the building should be obtained from the High School Administration Office. Their address is 1500 Park Street, Little Rock, Arkansas 72202. The Central High Museum and Visitor Center is located directly across the street from the school at 2125 West 14th Street, Little Rock, Arkansas 72202.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Setting the Stage

Prior to the Civil War, African Americans were not recognized as citizens. Slaves were considered property, which could be bought, sold, or transferred. Even former slaves and Free Blacks did not automatically enjoy the protections guaranteed to U.S. citizens. In New England, slavery ended gradually after the American Revolution. In Connecticut, slavery came to a complete end in 1848, although the majority of African Americans in the state were free by 1800. Many citizens of the New England states opposed slavery, but they did not necessarily approve of integrating African Americans into society as equals under the law. The colonizationist movement was strong in these states, proposing that African Americans would never be successfully integrated into white America, and that they should be returned to a homeland created for them in Africa.

Events in Canterbury, Connecticut, in the early 1830s brought race related issues to the forefront when a young teacher named Prudence Crandall admitted an African-American student to her boarding school and subsequently opened a school strictly for black females. The town's negative and ultimately violent reaction sparked heated debate, especially between colonizationists, who supported sending Free Blacks to colonies in Africa, and abolitionists. The events received national attention through newspapers such as The Liberator.

After the Civil War, African Americans continued to suffer economically, politically, and socially. Even with ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, which guaranteed rights of citizenship to "all persons born or naturalized in the United States," harsh discrimination continued. In 1896 the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson established the "separate but equal" doctrine, which provided a legal basis for segregated schools. Theoretically, African-American students were to receive a comparable education to white children, but this rarely was the case. The "separate but equal" policy continued until the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka determined that this policy violated the rights of African Americans to an equal education. Court-ordered desegregation affected school districts everywhere in the United States, but when nine African-American students attempted to integrate Arkansas' Little Rock Central High School amidst an angry mob in 1957, the eyes of the nation were upon them. The episode became the symbol and focus for the controversy over school segregation.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Eastern half of the United States.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Little Rock, Arkansas, and Canterbury, Connecticut (where Prudence Crandall operated her boarding school for young African-American women).

2. In what region of the country is Connecticut located? Was slavery permitted in Connecticut at one time? If so, when did it come to an end, before or after the Civil War?

3. In what region of the country is Arkansas located? Was Arkansas a slave state or free state prior to the Civil War?

4. The events that unite Canterbury and Little Rock occurred more than a century apart and in different regions of the country. What does this indicate about the struggle involved in securing civil rights for African Americans?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Prudence Crandall and the Canterbury Female Boarding School

In the fall of 1831, the residents of Canterbury, Connecticut, approached 27-year-old Prudence Crandall about opening a private school for young women in their community. Crandall accepted the invitation and paid $500 as a down payment to purchase the recently vacated Paine mansion located on the town's green. Having been educated at the Friends' Boarding School in Providence, Rhode Island, and having taught at local district schools, Crandall came to the position with a fine reputation as a teacher. The Crandall family, Quakers from Rhode Island, moved to south Canterbury when Prudence was young.

The Canterbury Female Boarding School enjoyed the complete support of the community and was soon a success. Subjects taught included reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, geography, history, chemistry, astronomy, and moral philosophy. Basic tuition and room and board cost $25 per quarter. Students paid extra fees for instruction in drawing, painting, music, and French. With student tuition, Crandall was able to pay off the $1500 mortgage within a year.

At the time Crandall opened her school in Connecticut, white and African-American children received a free elementary education at the district schools. No further public or private education was made available to black children. Crandall became aware of the injustices to African Americans in Connecticut and elsewhere through her housekeeper Marcia Davis, and Marcia's friend Sarah Harris, both African Americans. Sarah's father was the local distributor of the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. Marcia sometimes would leave copies of the newspaper where Crandall would find them.

In the fall of 1832, Sarah Harris asked Prudence Crandall to admit her to the Canterbury Boarding School. Originally from Norwich, Connecticut, a town traditionally having a larger population of African-American families, Harris hoped the education Crandall's academy offered could help her achieve her goal of returning to Norwich as a teacher. Crandall agreed to let Sarah attend the school as a day student. She immediately lost the support of the townspeople. A number of Canterbury's leading gentlemen, including the secretary of Crandall's Board of Visitors, supported the colonizationist movement, which feared the integration of the races and proposed sending all African Americans in America to Africa. This issue was being passionately debated at the time Crandall admitted Sarah Harris to her school.

Parents threatened to withdraw their daughters if Harris remained in the school. Crandall soon realized she must find some alternative to keep the school open. In the spring of 1833, she traveled to Boston to meet with William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator. They discussed the possibility of closing the academy to white students and reopening with an African-American student body. With Garrison's assistance she traveled throughout New England to meet with upper-middle class families who might be willing to send their daughters to the school. She soon realized this idea could be successful. Newspaper advertisements were placed announcing that as of April 1, 1833, the academy would reopen for the purpose of educating "young ladies and little misses of color." According to Crandall, "the sole object, at this school [was] to instruct the ignorant and prepare teachers for the people of color that they may be elevated and their intellectual and moral wants supplied."1 A delegation of town leaders urged her to abandon the project and led a general boycott of the school when Crandall refused.

Although the school opened with only three students, Crandall recruited others from Boston, Providence, and New York City. Enrollment soon rose to 24 students, most of whom were boarders. The curriculum was identical to that of Crandall's first Canterbury school. Both Crandall and her students endured harassment from angry townspeople. Shopkeepers refused to sell them food and townspeople pelted the building with stones and eggs. Under the shield of darkness, the school's opponents even attempted to set the building on fire in January 1834. Crandall's Quaker upbringing contributed to her moral convictions and her decision not to bend to public pressure. The Quakers strongly opposed slavery and promoted education for women and minorities. Crandall herself believed in the cause of immediate abolition.

So determined and influential were Crandall's opponents that, on May 24, 1833, the Connecticut General Assembly enacted a measure known as the Black Law. This act restricted African Americans from coming into Connecticut to get an education and prohibited anyone from opening a school to educate African Americans from outside the state without getting the town's permission. The law did not prevent African Americans that were residents of Connecticut from going to district schools. Convinced the Assembly's action was neither morally just nor constitutionally correct, Crandall ignored the law and continued to recruit and teach her students until her arrest on June 27, 1833.

Crandall spent one night in jail for violating the Black Law. At her trial on August 23, 1833, the jury failed to reach a verdict. The case went to a second trial in October 1833, where she was found guilty. Judge David Daggett told the jury, "It would be a perversion of terms, and the well-known rule of construction to say that slaves, free blacks or Indians, were citizens within the meaning of that term, as used in the Constitution. God forbid that I should add to the degradation of this race of men; but I am bound by my duty, to say they are not citizens." According to this argument, the Constitution did not entitle African Americans to the freedom of education. Crandall appealed the decision to Connecticut's Supreme Court. While she and her abolitionist supporters pursued their legal challenges to the Black Law, her school continued to operate. When supporters visited the school, Crandall's students performed a song for them, revealing their fear and sorrow:

Sometimes when we have walked the streets

Saluted we have been

By guns and drums and cow bells, too

And horns of polished tin.

With warnings, threats, and words severe

They visit us at times

And gladly would they send us off

To Africa's burning climes.2

The Black Law and Crandall's resistence to it sparked a year-long debate among New Englanders on the issues of abolition and colonization. The Liberator thundered against the injustice, and soon all of America knew of Canterbury and Prudence Crandall. The conflict allowed abolitionists to dramatize the evils of prejudice. Leaders in the movement helped Crandall recruit students for her school, gave her support, and provided for her financially.

On July 26, 1834, the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors dismissed the case against Crandall on a technical issue. The lower court decision that African Americans were not protected as citizens, however, remained standing. Although Crandall had won a technical legal victory and was free to return to her school, the townspeople of Canterbury would not accept the Supreme Court's decision. On the night of September 9, 1834, an angry mob broke in and ransacked the school building. With clubs and iron bars, the mob terrorized the students and broke more than 90 windows. What the Black Law and local ostracism had not been able to accomplish, this mob achieved. Fearing for the girls' safety, Crandall closed the school the following morning.

In 1834 Prudence Crandall married Calvin Philleo. They left their home in Canterbury shortly after the school closed. Her courage and persistence continued to win her national attention in abolitionist circles. She spoke and was entertained at banquets sponsored by abolitionists and African-American societies. In 1848 she moved to Illinois where she farmed land owned by her father and taught school. In 1877 she moved to Elk Falls, Kansas, where she started a school that served American Indians. In 1883, Mark Twain, a resident of Hartford, Connecticut, helped obtain a pension for Prudence Crandall from the Connecticut Assembly. He also offered to buy her former home in Canterbury for her retirement, but Crandall kindly declined the offer. She died in Elk Falls in 1890 at the age of 87.

Questions for Reading 1

1. How did Crandall come to understand the injustices against African Americans in the New England states? What was The Liberator? Who first showed it to her?

2. Why did Crandall close her school the first time? What did she do next? Why?

3. Why do you think the events at Canterbury captured such great attention at the time?

4. What was the Black Law? How did it affect Crandall's school legally? What was her reaction to the law?

5. What was the legal result of Crandall's trial?

6. What does the song that Crandall's students performed reveal about what they endured?

7. Why did Crandall close her school for good? What might you have done in her situation? How did she spend the rest of her life?

8. Based on this reading, how would you describe Prudence Crandall?

9. In 1984 Prudence Crandall became the official heroine of Connecticut. In what ways were Sarah Harris and her fellow African-American students heroines?

Reading 1 was adapted from Dr. Page Putnam Miller, "Prudence Crandall House" (Windham County, Connecticut) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1970; Marvis Olive Welch, Prudence Crandall: A Biography (Manchester, CT: Jason Publishers, 1983); and Randy Ross Ganguly, The Prudence Crandall Museum: A Teachers Resource Guide (Connecticut Historical Commission, State of Connecticut).

¹Randy Ross Ganguly, 67.

²Ibid., 68.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: All Eyes on Little Rock Central High

Built in 1927 at a cost of $1.5 million, Little Rock Senior High School, later to be renamed Little Rock Central High, was hailed as the most expensive, most beautiful, and largest high school in the nation. Its opening earned national publicity with nearly 20,000 people attending the dedication ceremony. The next two decades there were typical of those at most American high schools, but historic events in the 1950s changed education at Central High School and throughout the United States.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States made a historic ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka when it declared that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Thurgood Marshall, chief counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and future Supreme Court Justice, had successfully argued the case before the Supreme Court. As part of his argument to end segregation, he referenced the case Prudence Crandall's lawyers made against Connecticut's Black Law. As a result of the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, the "separate but equal" doctrine set forth in the Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson was no longer valid. In May 1955, after carefully considering how the ruling should be implemented, the Court stated that Federal District Courts would have jurisdiction over the desegregation plans of local school districts and that these plans should be formulated and put into effect "with all deliberate speed."

Arkansas was considered a moderate southern border state on the issue of race relations and civil rights. A few days after the Supreme Court's decision, the Little Rock School Board held a special meeting to discuss its impact on the city's schools. A unanimous resolution declared that the Board would comply and gradual desegregation would begin at the high school level in the 1957 school year. Central High was selected to be the first to desegregate with lower grades following over the next six years.

There was little open dissent among the city's white citizens in the three years of planning for the desegregation of Central High School. In January 1956, several African-American students attempted to enroll in Little Rock's schools. In response, lower courts judged the 1957 desegregation date to be in line with the Supreme Court's ruling and denied admittance to the students. The effort of African Americans to enroll in white schools flamed public interest in the desegregation plan. During the summer of 1957, a few months before Central High was to desegregate, opposition began to crystallize as the Capital Citizen's Council, the Little Rock version of a white citizen's council, and the Central High Mothers' League launched a media campaign against the School Board's plan and integration in general.

Amidst growing turmoil, the superintendent and staff interviewed African-American students who lived in the Central High district and expressed interest in participating in school integration. Out of the students selected, several later decided to stay at their all-black high school. The remaining students became known as the "Little Rock Nine." The co-editor of the Tiger, Little Rock Central High School's student newspaper, summarized the events surrounding the planned desegregation in the September 19, 1957, issue as follows:

Classes were scheduled to begin promptly at 8:45 a.m., September 3, at Little Rock Central High School when incidents began happening which caused the school to be the center of nationwide publicity. Photographs and articles have appeared in national magazines, and newspapers throughout the United States have told the story of how nine Negro students had been registered for admission to Central. To better understand the happenings of the past two weeks, here is a summary of the history of the school situation.

Supreme Court Rules

On May 17, 1954 the United States Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in the schools was unconstitutional. Just five days later the Little Rock School Board issued a policy statement that said it would comply with the Supreme Court decision when the Court outlined the method to be followed. In May, 1955 the School Board adopted a plan of gradual integration under which the high school grades would be integrated starting in September, 1957.

Injunction Proceedings

Pulaski Chancellor Murry O. Reed issued a temporary injunction against enrolling Negroes in Central High on August 29, after Mrs. Clyde Thomason, recording secretary of the Mother's League, had filed suit in Pulaski Chancery Court.

Federal District Judge Ronald N. Davies of North Dakota nullified the Pulaski Chancery Court injunction the next day and ordered the School Board to proceed with its gradual integration plan beginning with the opening of school on September 3.

Governor Calls Guard

Governor Orval Faubus called out the Arkansas National Guard and the State Police on the night of September 2 to surround the LRCHS campus with instructions to keep peace and order. About 270 Army and Air National Guard troops under the command of Colonel Marion Johnson formed lines for the two blocks along the front of the school. The first day of school drew a crowd of about 300 spectators; the troops had closed the streets around the school to all traffic.

There were groups of uniformed men posted at each entrance and all sides of the building with orders to admit only students, teachers, and school officials. Judge Davies again ordered integration to proceed at a hearing which lasted less than five minutes on the night of September 3.

Nine Negroes Arrive

Nine Negro students arrived to enroll at Central on the second day of school but were turned away by the National Guardsmen at the direction of Governor Faubus.

That afternoon Federal Judge Davies ordered an investigation by all offices of the Department of Justice to determine who was responsible for the interference of the court's order to proceed with integration. The National Guard remained on duty. A petition asking for a stay of the integration order was sought in the interest of education by the School Board on September 7, but it was denied by Judge Davies.

Gov. Accepts Summons

A week after school had opened, on September 10, Governor Faubus was served with a Federal Court summons. Federal Judge Davies ordered the Governor and the Arkansas National Guard made defendants in the case and scheduled a hearing for tomorrow, September 20. Later that day, the nine Negroes who had failed to enter LRCHS said they would not make another attempt until after the hearing. At a press conference after the summons had been accepted Governor Faubus said that the Guard Troops would remain at Central for the time being.

Historic Meeting Occurs

Last Saturday an unprecedented conference took place between President Eisenhower and Governor Faubus at Newport, Rhode Island, to discuss the school situation. Although many details have been written about this meeting, no definite statements have been made as to the possible outcome.

The October 3, 1957, issue of the Tiger continued the story:

Nine Negro students attended Little Rock Central High School last week for the first time in history. They arrived at the school Wednesday, September 25, accompanied by crack paratroopers of the U.S. Army's 101st Airborne Division. An Army station wagon carried the students to the front entrance of the building while an Army helicopter circled overhead and 350 armed paratroopers stood at parade rest around the building.Never before had Federal troops been used to enforce integration in a public school.

Third Attempt Made

This was the third attempt the Negro students had made to attend classes at Central. For three weeks the Arkansas National Guard had patrolled the school on orders of Governor Orval Faubus. Then on September 20 the troops were withdrawn by the Governor after the Federal Court had issued an injunction requiring him to withdraw the troops.

All was quiet over the week-end at CHS, but on Monday, September 23, eight of the Negro students enrolled at Central. Uncontrolled violence grew so swiftly in the area surrounding the school campus that city law enforcement officers decided it was wise to withdraw the Negro students shortly after noon on the same day.

Federal Troops Arrive

President Eisenhower took unprecedented action on September 24, when he called the Arkansas National Guard into active military service to deal with the Little Rock school integration crisis. President Eisenhower also authorized Secretary of Defense Wilson to use regular Army troops in addition to the National Guard Units.

Accordingly, about 1,000 paratroopers of the 101st Airborne division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, began arriving at the Little Rock Air Force Base on the evening of September 24. They immediately took up positions around the school.

General Advises Students

The Department of the Army designated Major General Edwin A. Walker chief of the Arkansas Military District.

As commander of the troops in the Little Rock area, Major General Walker addressed the student body and explained his position clearly.

All Quiet Within

Halls were quiet within the schools as the Negro students entered. They proceeded to their pre-arranged classes and school work went on just about as usual. At least two dozen soldiers without bayonets patrolled the halls.

Many Central students were absent; of the 2,000 enrolled, about 1,250 attended classes. On Friday the attendance was back up to 1450. At press time it was almost normal.

Although some of the students, teachers, and administration attempted to maintain a sense of normalcy, for the nine students that integrated Central High School it was like going to war every day. One of the Little Rock Nine, Melba Pattillo Beals, describes their experience in her book Warriors Don't Cry:

My eight friends and I paid for the integration of Central High with our innocence. During those years when we desperately needed approval from our peers, we were victims of the most harsh rejection imaginable. The physical and psychological punishment we endured profoundly affected our lives. It transformed us into warriors who dared not cry even when we suffered intolerable pain.¹

Integration affected both their lives at school and at home. At school these students were elbowed, poked, kicked, punched, and pushed. They faced verbal abuse from segregationists as well as death threats against themselves, their families, and members of the black community. At home, their families endured threatening phone calls; some of the parents lost their jobs; and the black community as a whole was harassed by bomb threats, gun shots, and bricks thrown through windows. While the students received some support from their community, they also were alienated by those who felt their actions jeopardized the safety of others.

Eight of the Little Rock Nine bravely finished the school year. One student was suspended and later expelled due to altercations with segregationists. In May 1958, with federal troops and city police on hand, Ernest Green, the only senior of the Little Rock Nine, graduated from Central High.

After that year, however, the story was far from over. Although ultimately unsuccessful, the Little Rock School Board made attempts to delay further desegregation. In August 1958, Governor Faubus called a special session of the state legislature to pass a law allowing him to close public schools to avoid integration. Faubus ordered Little Rock's high schools closed the following month, forcing approximately 3,700 high school students to seek alternative schooling during the 1958-59 school year. Finally, in June 1959, a federal court declared the state's school-closing law unconstitutional, and the schools reopened in the fall. Under the guidance of the new School Board, Little Rock Central High reopened in August 1959. Although a group of demonstrators marched to the school's opening, the local police broke up the mob and the school year began peacefully as several of the Little Rock Nine returned to Central High School.

Questions for Reading 2

1. Why do you think the Little Rock School Board decided to put off desegregation for three years after the 1954 ruling? Why do you think they did not attempt to desegregate all schools at once?

2. Why do you think some students tried to enroll before the scheduled integration date? What was the result?

3. Why do you think several African-American students selected to attend Central High ultimately decided not to switch schools? What might you have done in that situation?

4. Who published the Tiger? From the account presented by the Tiger articles what impression do you have about the events surrounding the integration of Central High? Does the article appear biased either for or against integration? Why or why not?

5. Why did Governor Faubus send units of the Arkansas National Guard to Central High? How do you think calling in the National Guard to keep the students out influenced public reaction to the integration of Central High?

6. Why did President Eisenhower call on the National Guard to protect the students? Why did he send the 101st Airborne Division? How might you have felt if you were part of the Arkansas National Guard called to first enforce segregation, and then enforce integration?

7. How have the two events discussed in Readings 1 & 2 influenced your understanding of the conflict that sometimes occurs between state and federal authorities?

8. How did the experience of students at Central High compare to those that attended Prudence Crandall's school? Reread the song lyrics found in Reading 1. Did they also apply to the Little Rock Nine? If so, how?

Reading 2 was compiled from "Little Rock High School" (Pulaski County, Arkansas) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1970; Georgia Dortch, "Central High Thrown in National Spotlight as it Faces Integration," the Tiger, September 19, 1957; "Integration Goes Forward at CHS," the Tiger, October 3, 1957; "Golden Years," Little Rock Central High School's 50th anniversary yearbook, published in 1977; and Melba Pattillo Beals, Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High (New York: Washington Square Press, 1994).

¹Melba Pattillo Beals, Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High (New York: Washington Square Press, 1994), 2.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: The Prudence Crandall Museum.

(National Park Service, Photo by Dennis Oparowski)

(National Park Service, Photo by Dennis Oparowski)

The 16-room mansion (built circa 1805) purchased for the Canterbury Female Boarding School was situated on the town green on three-quarters of an acre of land.

Questions for Photos 1 and 2

1. How would you describe this building? Does it look like a typical school? Explain your answer.

2. Where was the school located in the village of Canterbury? Why might Canterbury's citizens have purchased an existing house at this location to serve as the new school?

3. At one time, 24 students lived and attended school here. Based on these photos, do you think that this arrangement would have been difficult? Why or why not?

4. Where in the house do you think students slept? Where do you think the classrooms might have been located? Why?

Visual Evidence

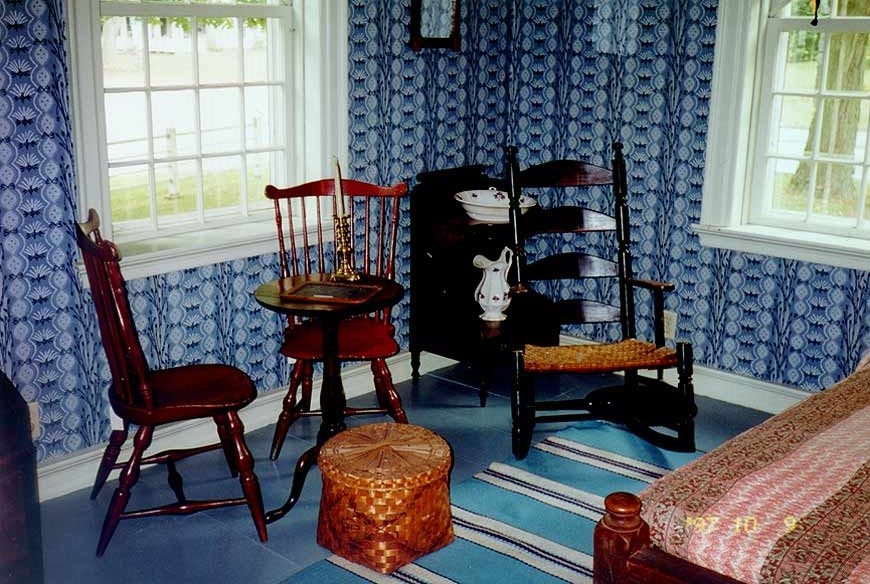

Photo 3: Prudence Crandall Museum, front entry from rear of house.

(National Park Service, Photo by Dennis Oparowski)

(Courtesy of the Prudence Crandall Museum, administered by the Connecticut Historical Commission, State of Connecticut)

Using correspondence, newspaper accounts, and legal documents, the Prudence Crandall Museum staff has pieced together some information on how the academy would have functioned in the house. Since classes were taught throughout the building, the eight rooms of the main house would have been used as multi-purpose rooms furnished with candle stands and worktables interspersed with writing desks, sofas, and side chairs. Documentation exists that the northeast front parlor was used as dormitory space and included hinged beds that could be moved out of the way during the day leaving room for study or meals.

The more formal southeast front parlor would have been set aside to entertain guests and host student recitations and programs. The second floor of the main house had combination bedroom, sitting, and study areas. The first floor of the back ell held a kitchen with cooking fireplace, pantry, and storage rooms. The second floor ell held remaining bedrooms for the students.

Questions for Photos 3 & 4

1. How would you describe the interior of the building? What features look like a house and what look like a school?

2. Why wouldn't the school have contained any traditional classroom space? Do you think this would have mattered? Why or why not? Why do you think the rooms were not remodeled into classrooms?

3. Do you think the appearance and layout of the school tell us something about people's attitudes towards the education of young women at the time? If so, what?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Little Rock Central High School today.

(Photo by and courtesy of Tod Swiecichowski)

Central High's dedication program indicated that the building had 100 classrooms with a capacity to seat 3,000 students. The building is 564 feet long and 365 feet wide. Other features of the building included an auditorium that seated 2,000, a cafeteria that seated 910, a greenhouse for biology and other science work, and 3,000 built-in or recessed lockers.

Questions for Photo 5

1. How would you describe this building?

2. Why do you think the residents of Little Rock were willing to spend so much money on this school? What does this indicate about the importance placed on education in the community?

3. How does the size, building style, building materials, etc. of Central High compare to that of the Canterbury Boarding School?

4. How does Central High's appearance compare to that of your school? What might account for some of the differences?

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Little Rock Central High School, front entrance.

(Photo by Cindy Momchilov/Camera Work, Inc.)

Little Rock Central High boasts four impressive statues of Greek goddesses over the front entrance. The statues represent Ambition, Personality, Opportunity, and Preparation. At the dedication service in 1927, Lillian McDermott, president of the School Board, claimed the new school "would stand...for decades to come [as] a public school where Ambition is fired, where Personality is developed, and where Opportunity is presented, and where Preparation in the solution of life's problems is begun."

Questions for Photo 6

1. Why might the architect have chosen these statues for the facade?

2. Discuss the irony in Lillian McDermmott's statement regarding her expectations for the school.

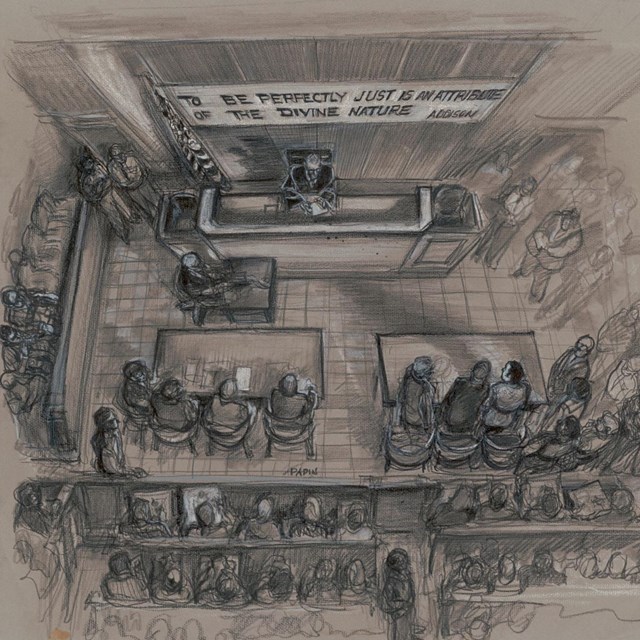

Visual Evidence

Photo 7: One of the "Little Rock Nine" braves a jeering crowd.

(Photo by and courtesy of Will Counts and the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette)

On September 4, 1957, an angry crowd of spectators greeted the African-American students as they attempted to attend Central High School for the first time. Elizabeth Eckford, who had not received a message to meet the other students, tried to enter the school by herself. Alone in a large crowd of hostile, jeering people, her attempts to enter the school were blocked by the Arkansas National Guard. She finally gave up and sat down at a bus stop enduring harassment from the mob until a white man and woman got her onto a bus and out of the area.

Television was a recent presence in American households at the time of the Central High School desegregation episode. Across the nation, in the newspapers and on television, Americans watched Little Rock's angry mob bar the entrance of Central High School to African-American students.

Questions for Photo 7

1. How do you think the media attention might have affected events at Little Rock Central High? Do you think the media attention would have made it easier or harder for the nine students integrating the school? Explain your answer.

2. How do you think Elizabeth Eckford felt at the time this photo was taken?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students better understand the relationship between the events that occurred in Canterbury, Connecticut, and Little Rock, Arkansas.

Activity 1: The Road to Educational Equality

Referring back to the information in Setting the Stage and Determining the Facts, ask students to circle the dates that they find and underline the event(s) that occurred. Next, have students construct a timeline of events related to school desegregation that are connected to the Prudence Crandall Museum and Little Rock Central High School. Encourage them to use their textbooks or other sources to fill in any gaps. After the timelines are complete, hold a class discussion to explore some of the challenges faced by African Americans and white supporters in the struggle for integrated schools.

Activity 2: From Canterbury to Little Rock

Have students complete the chart below. After they have finished, have them study the results and then write a brief essay comparing and contrasting events in Canterbury and Little Rock. They should look for similarities and differences between the people involved, the chronology of events, the characteristics of the communities, prevailing social and political conditions of the times, the end result, and so forth.

| Questions | Canterbury | Little Rock |

| 1. When did the significant events occur at the school? |

||

| 2. In what region of the country did the events occur? |

||

| 3. What was the prevailing attitude toward African Americans at the time? |

||

| 4. Was the school involved public or private? |

||

| 5. Was the community supportive of establishing the school? How can you tell? |

||

| 6. For whom did the community originally intend the school? |

||

| 7. What had prevented African Americans from attending the school in the first place? |

||

| 8. What alternatives did the community offer for educating African Americans? |

||

| 9. Did changes made by the local, state or federal government affect admission of African-American students to the school? If so, when and how? |

||

| 10. What was the reaction to African Americans attending the school? |

||

| 11. Did the local, state or federal government attempt to control public reaction? If so, what action did they take? |

||

| 12. What kind and how much publicity did the events receive? |

||

| 13. When and why was the school closed? Did it close permanently? What was the ultimate result of the events that occurred at the school? |

Activity 3: History of Public Education in the Local Community

Have students work in groups to research the history of public education in their community and prepare a report/presentation. Students should try to find answers to the following questions and then summarize how public education has changed over the years.

1.When was public education first available in the community? How were children educated prior to this?

2.What did the early school(s) look like? What grades and subjects were taught?

3.Were public schools segregated? If so, what group(s) was/were separated? Was there a legal basis for the segregation?

4.Was the community affected by desegregation? In what ways? How did the community react to desegregation?

5. Approximately how many schools--of all types--did the community have in the 1830s? 1950s? Today?

6. Approximately how many students were enrolled in public schools in your community in the 1830s? 1950s? Today?

Supplementary Resources

By looking at From Canterbury to Little Rock, students can more easily understand the enormity of the struggle involved in securing equal educational opportunities for African Americans. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of materials.

National Park Service

Central High School National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The park's Web page provides general information on the events that occurred at the school in the late 1950s.

Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The site is located at Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. Monroe was the segregated school attended by the lead plaintiff's daughter, Linda Brown, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in 1951. The park's Web page provides information on the park's establishment as well as directions and hours of operation.

The National Register of Historic Places online itinerary Travel America’s Diverse Cultures highlights the historic places and stories of America’s diverse cultural heritage. This itinerary seeks to share the contributions various peoples have made in creating American culture and history.

Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute

The Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute is an educational partnership between Yale University and the New Haven Public Schools designed to strengthen teaching and learning in schools. The Web site features curricular resources produced by teachers participating in Institute seminars, including "Slavery in Connecticut 1640-1848" and "From Plessy v. Ferguson to Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Rules on School Desegregation."

For Further Reading

Learners can find more information by referencing the following source: Adams, Ann-Marie (2010) The Origins of Sheff v. O’Neill: The Troubled Legacy of School Segregation in Connecticut. Available from Dissertations & Theses @ Howard University; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. See especially the chapter, "The Challenges of Black Education in Connecticut, 1820 - 1920"

Students and teachers interested in learning more about the the Civil Rights movement might want to look at the following books: Warriors Don't Cry by Melba Pattillo Beals (New York: Washington Square Press, 1994) is a powerful autobiographical account of the 1957 integration of Central High from a one of the Little Rock Nine students. Parting the Waters by Taylor Branch (New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1988) is an award-winning biography of Martin Luther King Jr., a history of the civil rights movement, and a portrait of an era. Weary Feet, Rested Souls, by Townsend Davis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998)is a comprehensive guidebook to the battlegrounds and back roads of the civil rights movement in the deep South.

***In addition to the cited sources above, this lesson plan was informed by the following scholarship: Adams, Ann-Marie (2010) The Origins of Sheff v. O’Neill: The Troubled Legacy of School Segregation in Connecticut. Available from Dissertations & Theses @ Howard University; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. See especially the chapter, "The Challenges of Black Education in Connecticut, 1820 - 1920"

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

The Judicial System

The Judicial SystemHow does the judicial system work? What is a federal court? Why are people trying to reclassify certain offenses?

-

Federalism

FederalismWhat is federalism? How have some Americans used debates about federalism to promote segregation?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

Tags

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- education

- school desegregation

- connecticut history

- connecticut

- african american education

- african american history

- arkansas

- arkansas history

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- women's history

- art and education

- civics

- mid 19th century

- late 20th century

- shaping the political landscape

- womens history

- women leaders

- women in the workplace

- womens work

- women and education

- twhplp

- cwr aah

- wwii aah