Last updated: January 7, 2023

Article

Boston's Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad refers to the effort -- sometimes spontaneous, sometimes highly organized -- to assist persons held in bondage in North America to escape from slavery. While most runaways began their journey unaided and many completed their self-emancipation without assistance, each decade in which slavery was legal in the United States saw an increase in the public perception of a secretive network and in the number of persons willing to give aid to the runaway. [1]

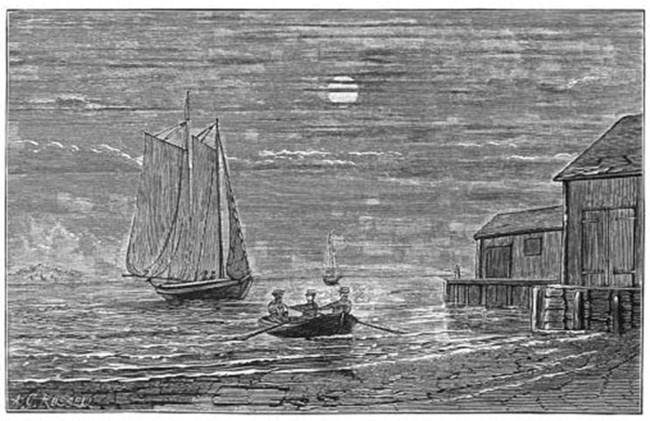

Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston by Austin Bearse, 1881.

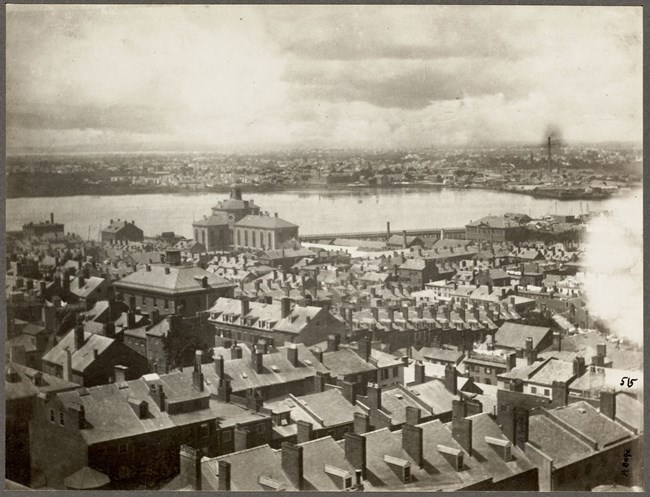

As the capitol and largest city of one of the earliest states to abolish slavery, Boston served as a destination for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. Boston's tightly knit free Black community provided a welcome sanctuary for those making their way to freedom.

As a port city, Boston provided a crucial avenue of escape, with most of its well-known freedom seekers arriving by sea as stowaways on ships that departed from southern ports. Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns, among others, used this method to reach Boston. Further, many Black Bostonians who worked along the harbor provided essential communication to those who arrived in the city.

Courtesy of the Boston Pictorial Archives, Boston Public Library

In their community nestled on the north slope of Beacon Hill, Black Bostonians opened their homes and churches to those escaping on the Underground Railroad. For example, Lewis and Harriet Hayden, who fled slavery themselves, established their home on Southac (now Phillips) Street as a crucial safe house on the Underground Railroad. On the same street, Reverend Leonard Grimes headed the Twelfth Baptist Church, often referred to as the "Fugitive Slave's Church" for its large congregation of southern born members who fled slavery to Boston. The African Meeting House on Smith Court, a church and community center, hosted many gatherings of organizations dedicated to assisting those escaping bondage. The New England Freedom Association, for example, held many of its meetings at the African Meeting House with the stated purpose to:

extend a helping hand to all who may bid adieu to whips and chains, and by the welcome light of the North Star, reach a haven where they can be protected from the grasp of the man-stealer…[2]

The New England Freedom Association provided money, clothing, and information along with other necessities to help those seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad.

With the passage of the new Fugitive Slave Law as part of the Compromise of 1850, Boston's abolitionist community grew increasingly militant in their Underground Railroad activity. This hated law strengthened the earlier fugitive slave laws by engaging federal marshals as slave catchers, imposing high fines and imprisonment for those who helped a fugitive, and mandating that state and local authorities as well as citizens assist in the execution of this law.

Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, Black activists met at the African Meeting House on October 5, 1850 to plan their collective response. This group included William Cooper Nell and Lewis Hayden, two of Boston's most prominent underground railroad operatives. William Craft, who escaped slavery with his wife Ellen, also participated in this meeting and served as its Vice-President. These community activists promised a sustained fight against the federal government and militant resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law. When slave catchers soon came looking for the Crafts, these abolitionists put their words into action and succeeded in thwarting the attempt to capture the famous fugitive couple.

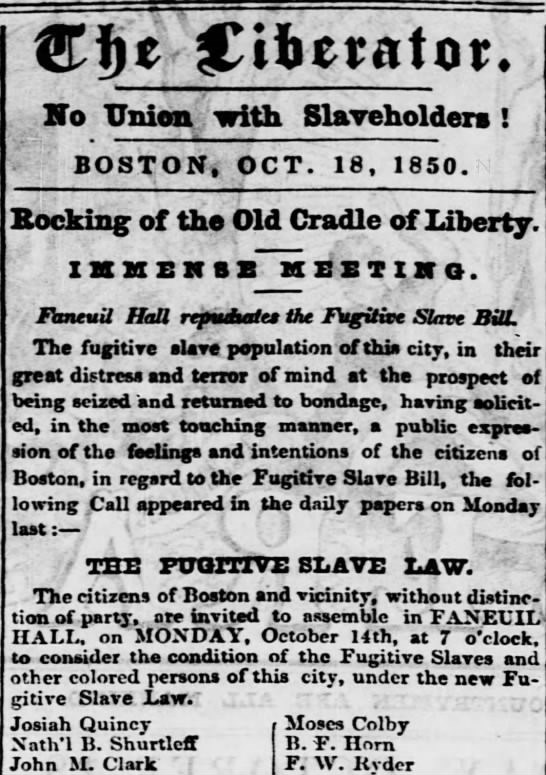

Later that month, a larger bi-racial crowd gathered at Faneuil Hall, Boston’s revered "Cradle of Liberty" most known for its central role in the years leading to the America Revolution. The Liberator, a major abolitionist newspaper, reported that this meeting drew thousands of participants to Faneuil Hall. The prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had escaped slavery years before, riled the crowd with his warning…

If you are ... prepared to see the streets of Boston flowing with innocent blood, if you are prepared to see sufferings such as perhaps no country ever before witnessed, just give in your adhesion to the fugitive slave bill - you, who live on the street where the blood first spouted in defense of freedom; and the slave- hunter will be here to bear the chained slave back, or he will be murdered in your streets.[3]

At this meeting, Bostonians formed a new Committee of Vigilance and Safety to "take all measures that they shall deem expedient to protect the colored people of this city in the enjoyment of their lives and liberties…"[4] This new Vigilance Committee provided valuable assistance to those escaping slavery through Boston for the duration of the Fugitive Slave Law years in the form of shelter, clothing, money, legal aid, medical attention, and passage further north.

Boston Public Library

In addition to protesting the fugitive slave laws and providing shelter and assistance to freedom seekers, some Bostonians engaged in daring rescue attempts of those arrested by the slave catchers. For example, in 1836, Black women staged a bold and successful courtroom rescue of Eliza Small and Polly Ann Bates, who escaped from Baltimore, in an event known as the Abolition Riot.[5] Similarly, in 1851, Black Bostonians rescued Shadrach Minkins in a brazen daytime assault on the courthouse. Not all efforts succeeded, however, as authorities foiled the plot to rescue Thomas Sims in 1851 and forcibly repelled the attempt to free Anthony Burns in 1854.

Though hundreds of documented people, and likely more that we will never know, successfully escaped slavery through Boston on the Underground Railroad, not all of them achieved the freedom they sought. High profile direct action such as the rescue of Shadrach Minkins alerted authorities to the power of Boston's abolitionist community. Federal slave catchers took further precautions in future cases such as those of Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns that ensured they successfully impeded the would-be rescuers and returned both Sims and Burns to slavery.

However, by the mid-1850s, after the tragic rendition of Anthony Burns by an overwhelming military force, public opinion began to shift, even among previous supporters of the Fugitive Slave Law. For example, Amos Lawrence, of the wealthy industrialist family, famously remarked that "we went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs," and, following Burn's rendition, "waked up stark mad Abolitionists."[6] The Burns case inspired a state-wide petition leading to the passage of a stringent new Personal Liberties Law in 1855. Although the Fugitive Slave Law remained in effect until the Civil War, this new Personal Liberties Law made it nearly impossible to publicly return another freedom seeker from the free soil of Massachusetts.[7]

Through their collective resistance and direct action, Black Bostonians and their allies continued to shelter and assist hundreds of freedom seekers throughout the duration of the Fugitive Slave Law years. They tirelessly and selflessly acted upon their resolution that "eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, and that they who would be free, themselves must strike the blow."[8] In doing so, they transformed Boston into an integral hub on the Underground Railroad's network to freedom.

Footnotes

[1] National Park Service, Underground Railroad Resources in the U.S. Theme Study. 2000.3 https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/upload/UndergroundRailroad.pdf

[2] William Cooper Nell, "Meeting of the New England Freedom Association," in William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, ed. Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002), 146-147; Also found in a slightly different format in The Liberator (Boston, MA), Dec. 12 1845.

[3] The Liberator (Boston, MA), Oct. 18, 1850, p.3.

[4] The Liberator (Boston, MA), Oct. 18, 1850, p.2

[5] James O. Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1979, 1999), p. 107.

[6] Robert K. Sutton, "The Wealthy Activist Who Helped Turn 'Bleeding Kansas' Free," Smithsonian Magazine, Aug. 16, 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/wealthy-activist-who-helped-turn-bleeding-kansas-free-180964494/

[7] "Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act (1855)," US History Documents, accessed July, 2020, http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/US_History_reader/Chapter5/masspersliberty.htm

[8] William Cooper Nell, "Meeting of the Colored Citizens of Boston," in William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, ed. Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002), p. 270.