Last updated: January 7, 2023

Article

“The Whole Land is Full of Blood”: The Thomas Sims Case

Boston served as a destination for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers arriving in the city found that Boston's tightly knit free Black community provided support and a welcome sanctuary as they began their new lives. This article highlights the journey of one freedom seeker, Thomas Sims, who escaped to Boston. To explore additional stories, visit Boston: An Underground Railroad Hub.

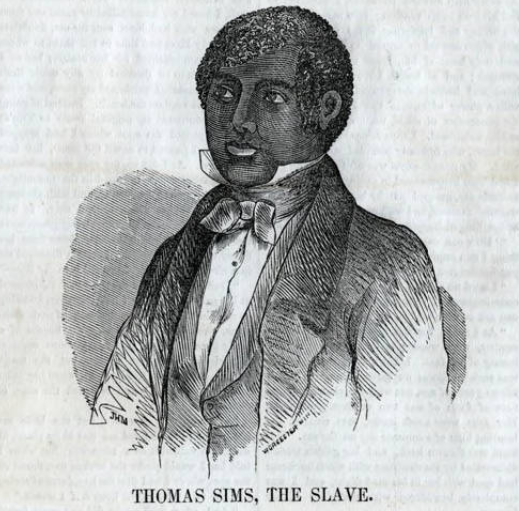

Similar to many other freedom seekers, Thomas Sims' path to emancipation took many years and several attempts. Born enslaved in Georgia, Sims escaped bondage by hiding on a ship headed to Boston. A few weeks after his self-liberation, authorities captured Sims under the Fugitive Slave Law and returned him to slavery. After living several more years enslaved and being sold across the South, Sims permanently achieved freedom during the American Civil War by escaping north in a 'dug-out boat.'

Explore the story map below to learn about Thomas Sims' journey to freedom. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes:

[1] Trial of Thomas Sims, on an issue of personal liberty, on the claim of James Potter, of Georgia, against him, as an alleged fugitive from service: Arguments of Robert Rantoul, jr., and Charles G. Loring, with the decision of George T. Curtis, Boston, April 7-11, 1851. Phonographic report by Dr. James W. Stone (Commonwealth Building. No. 60 Washington Street, Boston: Wm. S. Damrell and Co., 1851), https://archive.org/details/trialofthomassim00sims/mode/2up, 46-47.

Image: “Wendell Phillips,” Gleason's Pictorial vol. 1, no. 1, (May 3, 1851): 4, https://cdm.bostonathenaeum.org/digital/collection/p13110coll5/id/4316.

[2] Leonard W. Levy, "Sims' Case: The Fugitive Slave Law in Boston in 1851," The Journal of Negro History vol. 35, no. 1 (Jan., 1950), 43

Image: B. W. (Benjamin West) Kilburn, "Boston Light, Boston Harbor, Mass." Photograph (Littleton, N.H.: Photographed and published by B.W. Kilburn, 1878), Digital Commonwealth, accessed September, 2020, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/7p88d0093.

[3] Levy, "Sims' Case," 64.

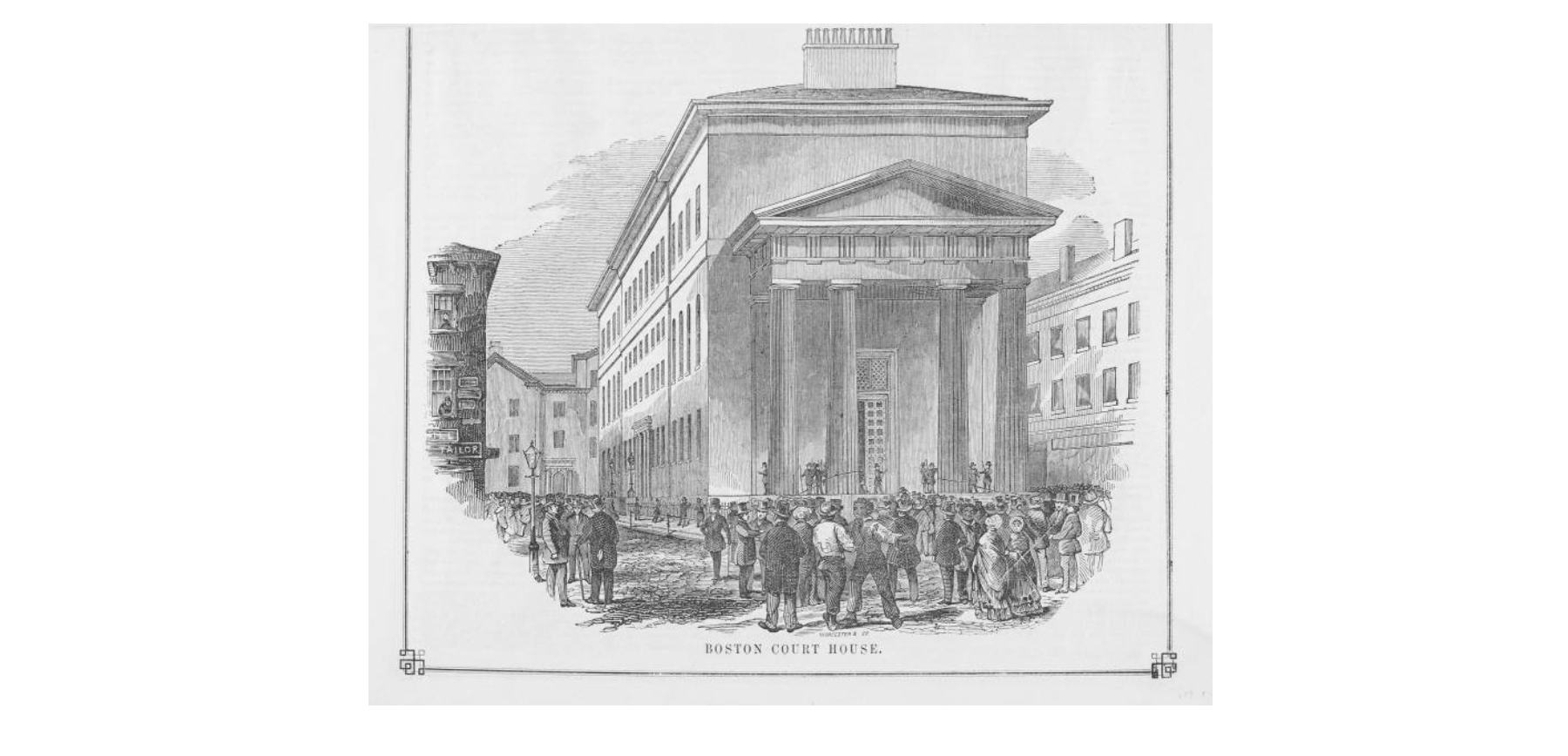

Image: “Boston Court House,” Gleason's Pictorial vol. 1, no. 1, (May 3, 1851): 5, https://cdm.bostonathenaeum.org/digital/collection/p13110coll5/id/5443/rec/1.

[4] Stanley W. Campbell, Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1968), 119.

[5] Levy, "Sims' Case," 68.

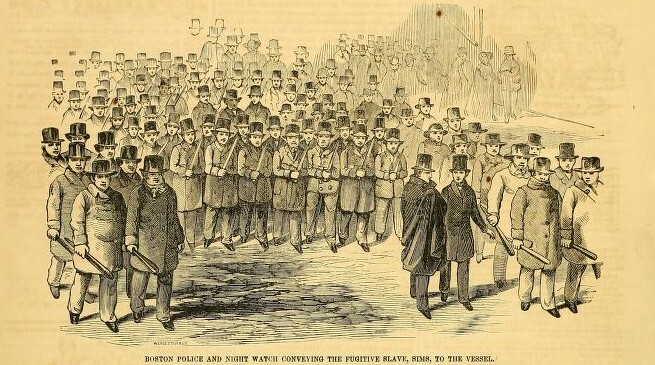

Image: “Boston Police and Night Watch Conveying the Fugitive Slave, Sims, to the Vessel,” Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, vol. 1, 1851, accessed September 2020, 44, https://archive.org/details/gleasonspictoria01glea/page/44/mode/2up.

[6] The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), April 18, 1851, 2.

[7] "'The whole land if full of blood,' 1851, A Spotlight on a Primary Source by James W. C. Pennington," History Resources, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, accessed September 2020, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/whole-land-full-blood-1851.

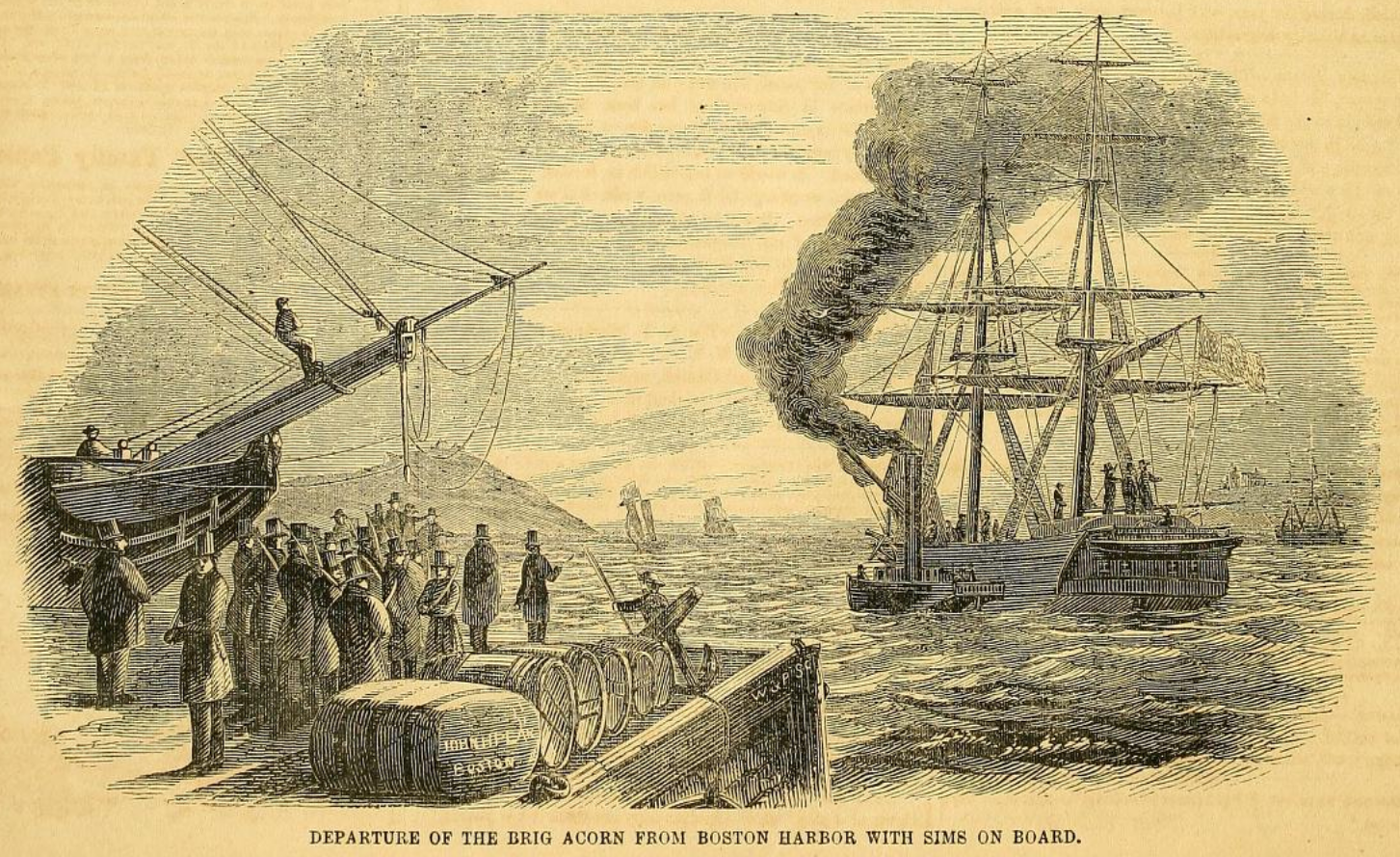

Image: “Departure of the Brig Acorn From Boston Harbor with Sims on Board,” Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, vol. 1, 1851, accessed September 2020, 44, https://archive.org/details/gleasonspictoria01glea/page/44/mode/2up.

[8] "A letter from Francis Jackson to Lydia Maria Child about Thomas Sims, who was arrested and re-enslaved under the Fugitive Slave Law, 1860," Digital Public Library of America, accessed September 2020, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/incidents-in-the-life-of-a-slave-girl-by-harriet-jacobs/sources/1140.

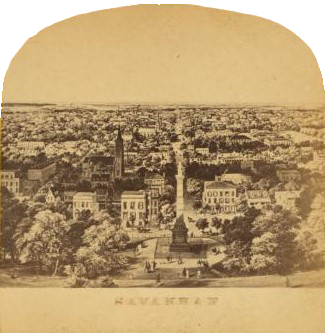

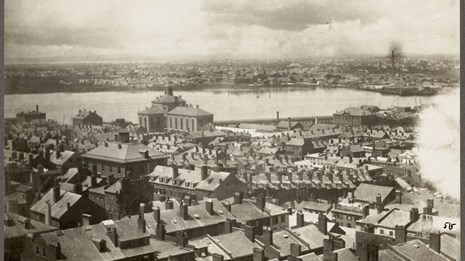

Image: "Panoramic view of Savannah," The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library, New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed September 16, 2020, http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-56da-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

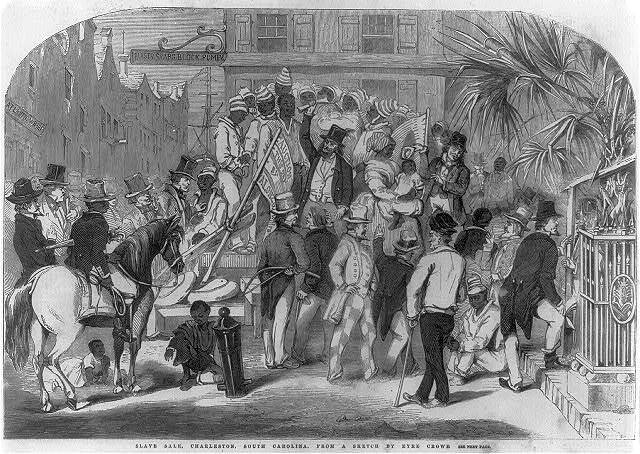

[9] "A letter from Francis Jackson."Image: “Slave sale, Charleston, S.C.,” 1856, Sketch, accessed September 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006687271/.

[10] "A letter from Francis Jackson."

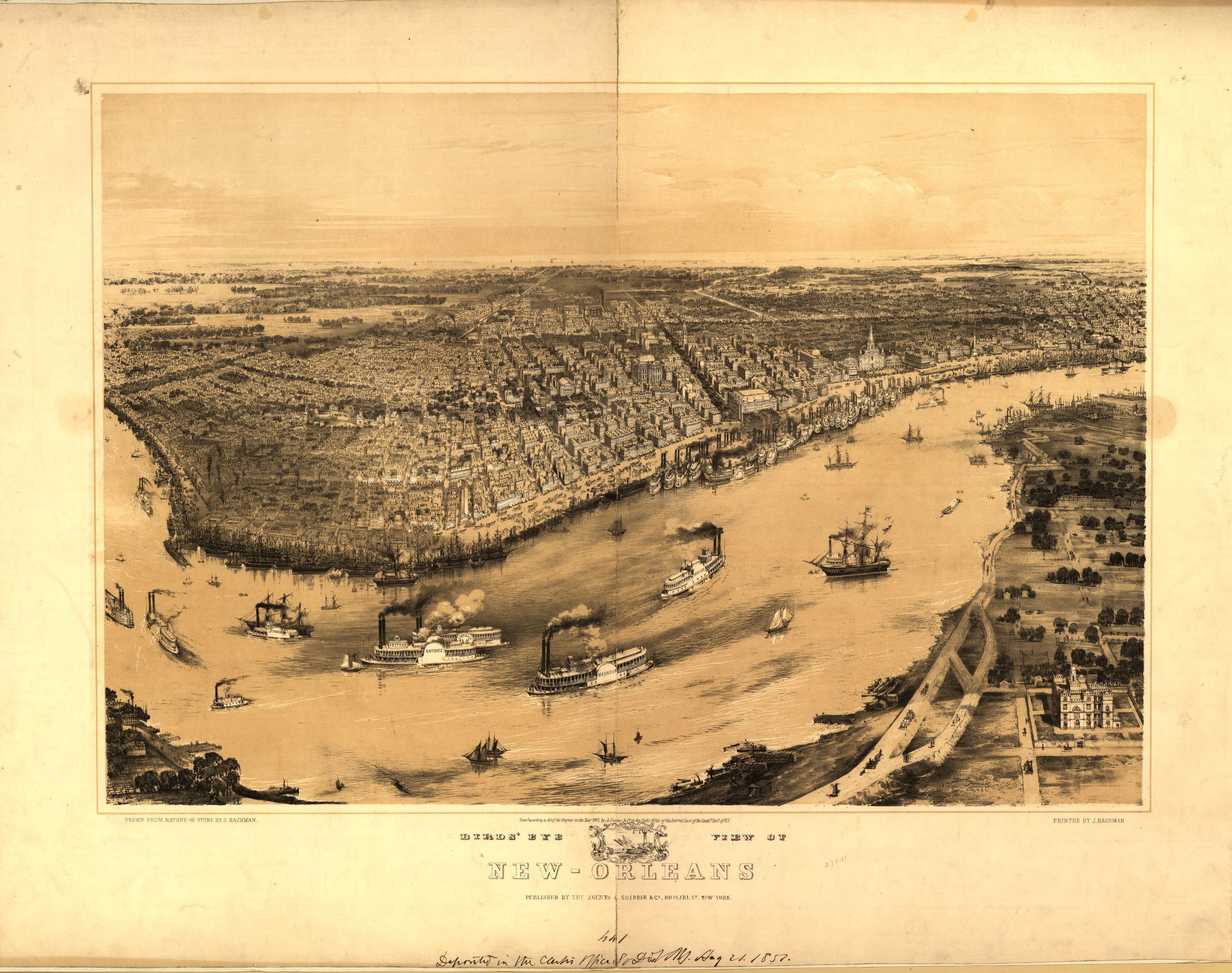

Image: John Bachmann, “Birds' eye view of New-Orleans / drawn from nature on stone by J. Bachman i.e., Bachmann,” New Orleans, Louisiana, United States, (New York: Published by the agents A. Guerber & Co. Photograph, ca. 1851), accessed September 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/93500720/.

[11] "A letter from Francis Jackson."

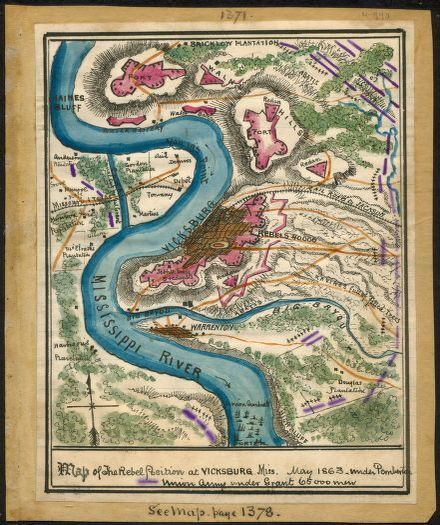

Image: Robert Knox Sneden, “Map of the rebel position at Vicksburg, Miss., May” [S.l., to 1865, 1863] Map, accessed September 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/gvhs01.vhs00140/.

[12] "A letter from Francis Jackson."

[13] William Cooper Nell, William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, edited by Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press 2002), 641.

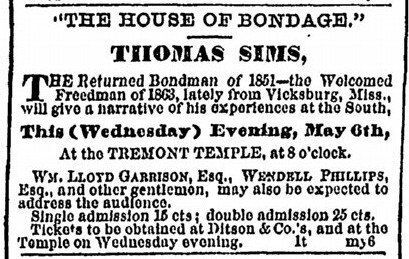

Image: “The House of Bondage,” Boston Herald, May 6, 1863, accessed September 2020, https://mississippiconfederates.wordpress.com/2013/09/28/a-remarkable-incident-the-escape-of-thomas-sims-from-vicksburg/.

[14] Jeff T. Giambrone, "A Remarkable Incident: The Escape of Thomas Sims from Vicksburg," Mississippians in the Confederate Army, September 28, 2013, accessed September 2020, https://mississippiconfederates.wordpress.com/2013/09/28/a-remarkable-incident-the-escape-of-thomas-sims-from-vicksburg/.

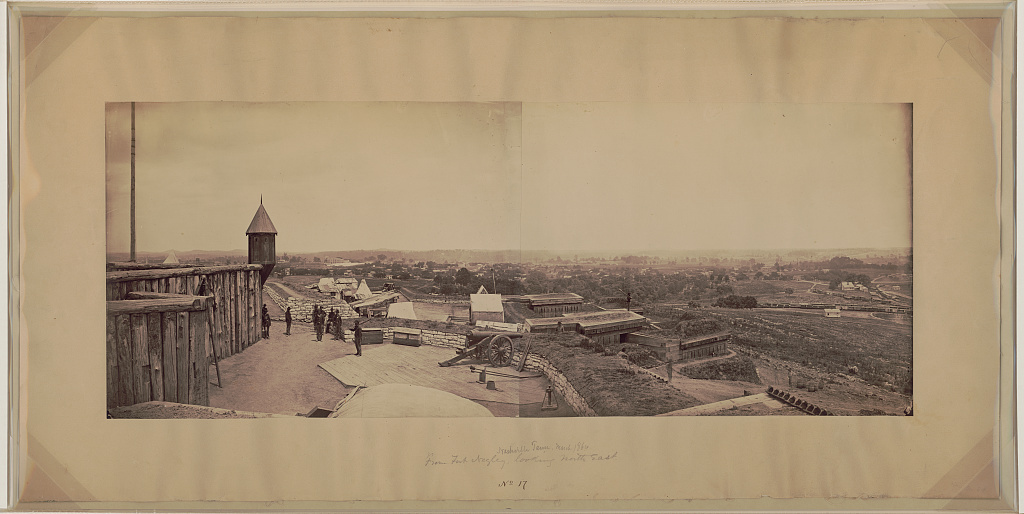

Image: George N. Barnard, “Nashville, Tenn., from Fort Negley looking northeast,” Fort Negley, Nashville, Tennessee United States, March, 1864, Photograph, accessed September 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007662878/.

[15] Robert S. Davis, "Chattanooga History Column: Thomas Sims Epic Struggle for Freedom," Chattanooga Times Free Press, February 5, 2017, accessed September 2020, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/opinion/columns/story/2017/feb/05/davis-lave-thomsims-epic-struggle-freedom/410943/.

[16] Davis, "Chattanooga History Column: Thomas Sims Epic Struggle for Freedom."

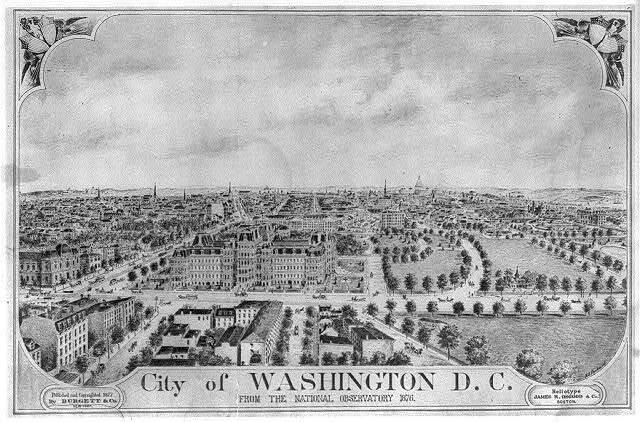

Image: “City of Washington, D.C. from the National Observatory,” ca. 1877, Photograph, accessed September 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007682995/.