Last updated: January 5, 2026

Article

Faneuil Hall, the Underground Railroad, and the Boston Vigilance Committees

While most known for its role as a site of colonial protest during the American Revolution, Faneuil Hall also served as an important gathering space for public dissent and organized resistance to slavery and the fugitive slave laws of the country. Long cherished as the "Cradle of Liberty," Faneuil Hall played an integral role in Boston's Underground Railroad network.

Beginning in the late 1830s, Boston's abolitionists began regularly using Faneuil Hall to host their meetings and rallies. Oftentimes, they called these meetings in response to high profile fugitive slave cases in the city. The abolitionists not only protested the arrest of fugitive slaves but also used the space to actively organize against the fugitive slave laws. With protests and petitions, they pressured state and local officials to resist enforcing these federal laws. Further, they formed vigilance committees to assist those seeking freedom on the Underground Railroad, encouraging supporters to help those in need and thwart the slave catchers.

Boston Public Library

For example, in 1842, George Latimer escaped from slavery in Virginia and came to Boston seeking his freedom. His arrest under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 prompted major protests throughout the city. On October 30, 1842, abolitionists gathered in Faneuil Hall to express their outrage and inspire action against Latimer’s arrest. They resolved that "this meeting protests…against the deliverance of George Latimer, into the hands of his pursuers," and that Massachusetts is "solemnly bound to give succor and protection to all who may escape from the prison-house of bondage, and flee to her for safety." They further declared that:

if the soul-traders and slave-drivers of the South imagine that Massachusetts is slave-hunting ground, on which they may run down their prey with impunity…they will find themselves mistaken.[1]

Though Bostonians quickly purchased Latimer's freedom, his case galvanized the abolitionist community of Massachusetts into further political action. They soon gathered more than 64,000 signatures on a petition presented to the Massachusetts legislature. This petition resulted in the passage of the 1843 Personal Liberty Act, which "forbade Massachusetts officials or facilities from being used in the apprehension of fugitive slaves and represented a major victory for abolitionist forces."[2]

The Liberator, October 2, 1846.

In 1846, another fugitive slave case rocked Boston, prompting an even larger protest at Faneuil Hall. The case involved a freedom seeker simply known as George, who escaped slavery from Louisiana by stowing himself on a Boston bound ship. When discovered onboard, the ship’s captain had George confined, and despite the efforts of local abolitionists, sent him back to the South. Bostonians, roused by this case, gathered at Faneuil Hall. The Liberator, Boston's major abolitionist newspaper, reported on this "Great Faneuil Hall Meeting for the Prevention of Illegal Seizures of Slaves." Presided over by former president John Quincy Adams, this meeting reportedly drew 5,000 people and culminated with the appointment of a Vigilance Committee to protect those illegally arrested as fugitives.[3] This 1846 Vigilance Committee encouraged its members to "avoid giving slave catchers any "aid or counsel" while offering "comfort and help to any fugitive slaves who may be thrown upon our hospitality."[4]

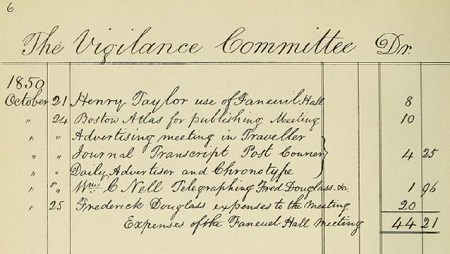

Francis Jackson, Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, Cape Cod Community College Archives.

With the passage of the new harsher Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Bostonians once again flocked to Faneuil Hall in protest. In the article, "Rocking the Old Cradle of Liberty – Immense Meeting – Faneuil Hall repudiates the Fugitive Slave Bill," The Liberator reported that this meeting, once again, drew thousands of people to Faneuil Hall. The prominent abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had escaped slavery years before, riled the crowd with his warning…

If you are ... prepared to see the streets of Boston flowing with innocent blood, if you are prepared to see sufferings such as perhaps no country ever before witnessed, just give in your adhesion to the fugitive slave bill - you, who live on the street where the blood first spouted in defense of freedom; and the slavehunter will be here to bear the chained slave back, or he will be murdered in your streets.[5]

At this meeting, the abolitionists asserted that "our moral sense revolts against the new Fugitive Slave Law, believing it to involve the height of injustice and inhumanity" and pledged:

to our colored fellow-citizens who may be endangered by this law all of the aid, co-operation, and relief…and we accordingly advise fugitive slaves and other colored inhabitants of this city and vicinity to remain with us…We have no fear that any one will be taken back to the land of bondage.[6]

Attendees at this meeting formed a new Committee of Vigilance and Safety to "take all measures that they shall deem expedient to protect the colored people of this city in the enjoyment of their lives and liberties…"[7] This Vigilance Committee provided valuable assistance to those escaping slavery through Boston in the form of shelter, clothing, money, legal aid, medical attention, and passage further north for the duration of the Fugitive Slave Law years.

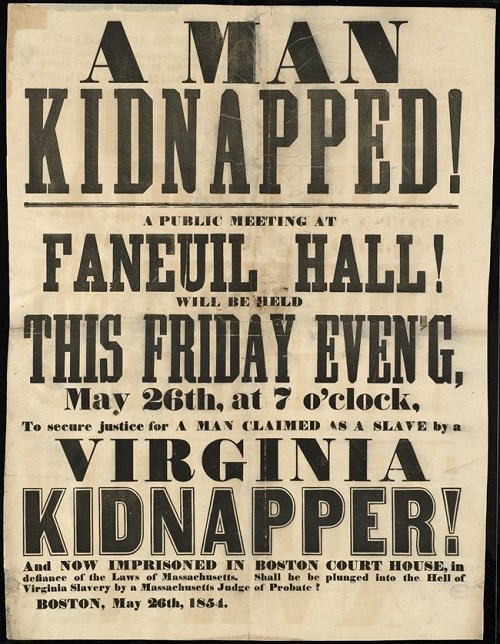

Boston Public Library

Faneuil Hall also played a prominent role in Boston's most infamous fugitive slave case. On May 26, 1854, thousands once more gathered at Faneuil Hall, this time to protest the capture of Anthony Burns, who escaped from Virginia. Arrested under the Fugitive Slave Law, authorities held Burns captive at the nearby courthouse. Echoing the earlier rhetoric of the American Revolution, the abolitionists declared that "nothing so well becomes Faneuil Hall as the most determined resistance to a bloody and overshadowing despotism."[8] One of the meeting’s organizers, Theodore Parker, warned that "Liberty is the end, and sometimes peace is not the means towards it…"[9]

As the meeting continued, someone interrupted by shouting "A crowd of negroes is storming the courthouse."[10] While some of the meeting’s organizers called for restraint, others flooded out of Faneuil Hall to help in the attempted courthouse rescue. Unfortunately for Burns, the rescue attempt failed, and Bostonians watched in protest as a military force escorted him back to slavery in the days ahead. However, within nine months, Bostonians raised the funds and purchased Anthony Burns' freedom and he returned north a free man.

Although its renown as "The Cradle of Liberty" hearkens back to the hallowed days of the American Revolution, this nickname is equally appropriate when considering the abolitionist and Underground Railroad history of Faneuil Hall.

Footnotes

[1] The Liberator, November 4, 1842.

[2] James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians; Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, Revised Edition (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999), 108.

[3] The Liberator, October 2, 1846.

[4] Dean Grodzins, “Constitution or No Constitution, Law or No Law: The Boston Vigilance Committees, 1841-1861” in Matthew Mason, Katheryn P. Viens, and Conrad Edick Wright, eds., Massachusetts and the Civil War: The Commonwealth and National Disunion, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 59.

[5] The Liberator, October 18, 1850.

[6] The Liberator, October 18, 1850.

[7] The Liberator, October 18, 1850.

[8] The Liberator, June 2, 1854.

[9] The Liberator, June 2, 1854.

[10] The Liberator, June 2, 1854.