Last updated: August 5, 2022

Article

"God made me a man- not a slave": The Arrest of Anthony Burns

Boston served as a destination for many people escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers arriving in the city found that Boston's tightly knit free Black community provided support and a welcome sanctuary as they began their new lives. This article highlights the journey of one freedom seeker, Anthony Burns, who escaped to Boston. To explore additional stories, visit Boston: An Underground Railroad Hub.

In May 1854, slave catchers arrested Anthony Burns, a 20 year old freedom seeker who escaped slavery in Virginia. His arrest sparked major protests, a failed courthouse rescue, a military takeover of downtown Boston, and, ultimately, a return to slavery by the federal government. The arrest of Anthony Burns became a flash-point for many Bostonians who had remained silent on the issue of slavery and the abolitionist movement. Ultimately freed through the efforts of Boston's abolitionists, Burns attended school at Oberlin College and trained to become a minister. Follow the inspiring story of Anthony Burns through our interactive story map.

Explore the story map below to learn about Anthony Burns' journey to freedom. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll down to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] Earl M. Maltz, Fugitive Slave on Trial (Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2010), 55.

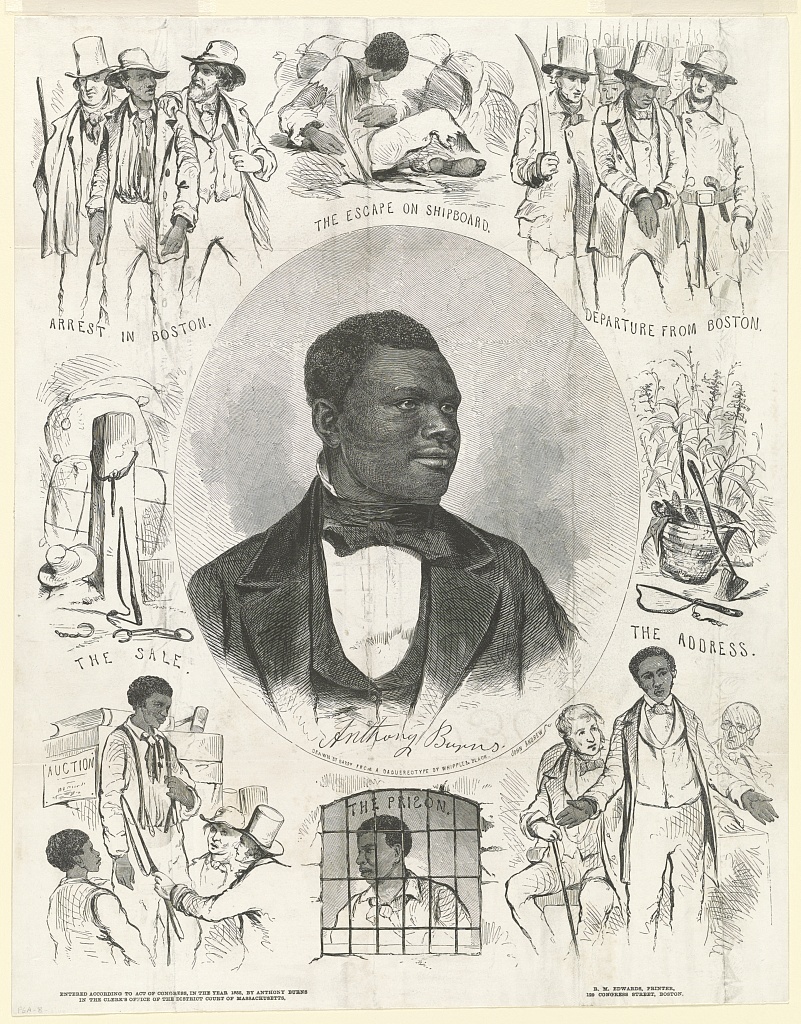

Image: John Andrews, "Anthony Burns / drawn by Barry from a daguereotype [i.e. daguerreotype] by Whipple & Black ; John Andrews, sc." (Boston : R.M. Edwards, printer, 129 Congress Street, c. 1855), Library of Congress, accessed September, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003689280/.

[2] Charles Emery Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History (Boston: J.P Jewett and Co, 1856), 162.

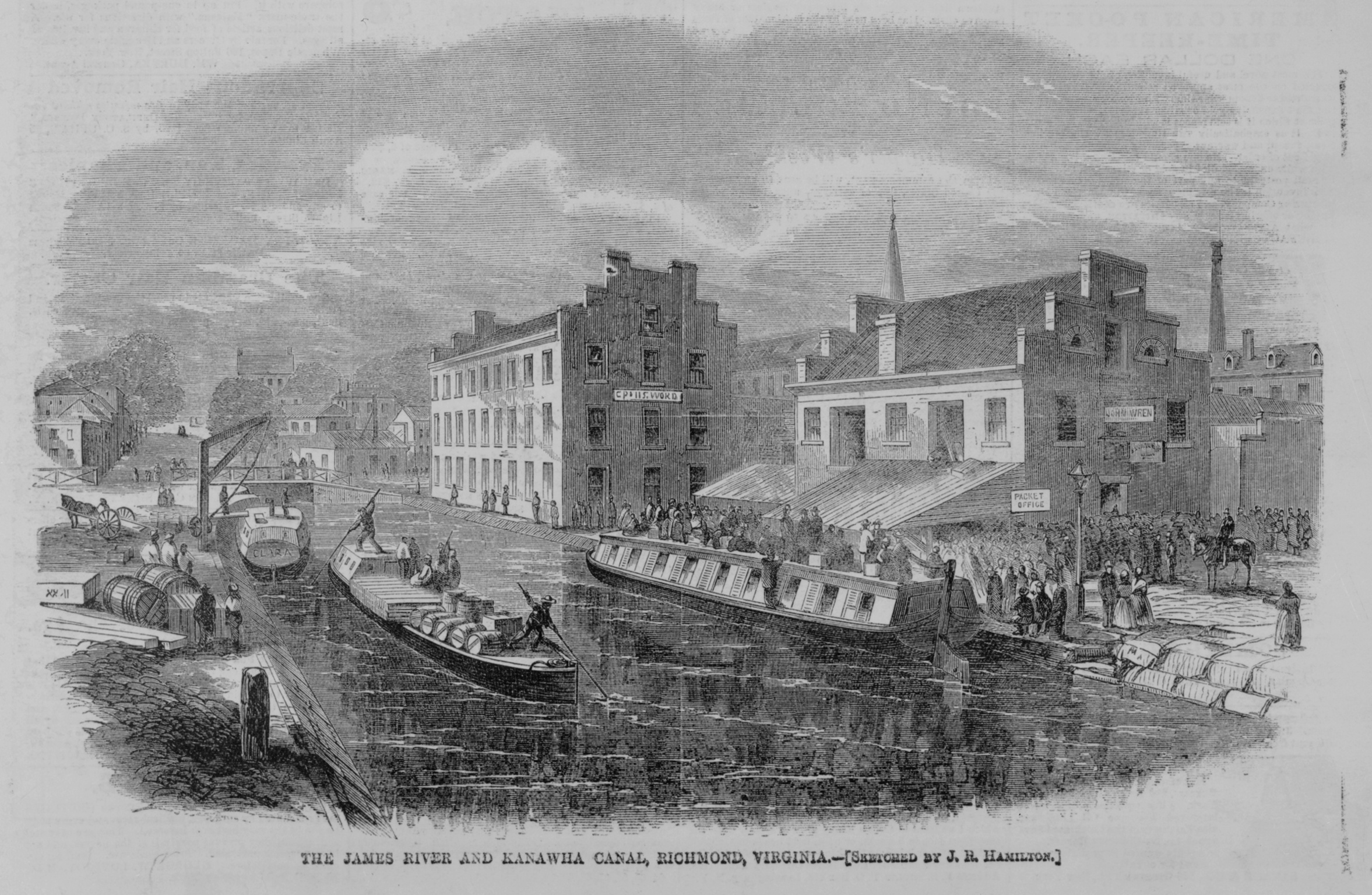

Image: John R. Hamilton, "The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad, Virginia - train starting out from Richmond The James River and Kanawha canal, Richmond, Virginia / / sketched by J.R. Hamilton," October 14, 1865, Library of Congress, accessed September, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003689065/.

[3] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 172-180.

[4] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 15.

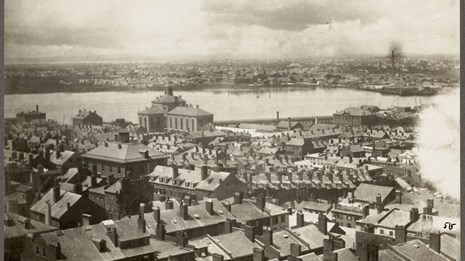

Image: Robert Havell, "View of the city of Boston from Dorchester heights / painted & engraved by Robt. Havell ; coloured by Havell & Spearing" (New York : Published by Robt. Havell, 172 Fulton St., c. 1841), Library of Congress, accessed September 2020, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672548/.

[5] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 180.

[6] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 28.

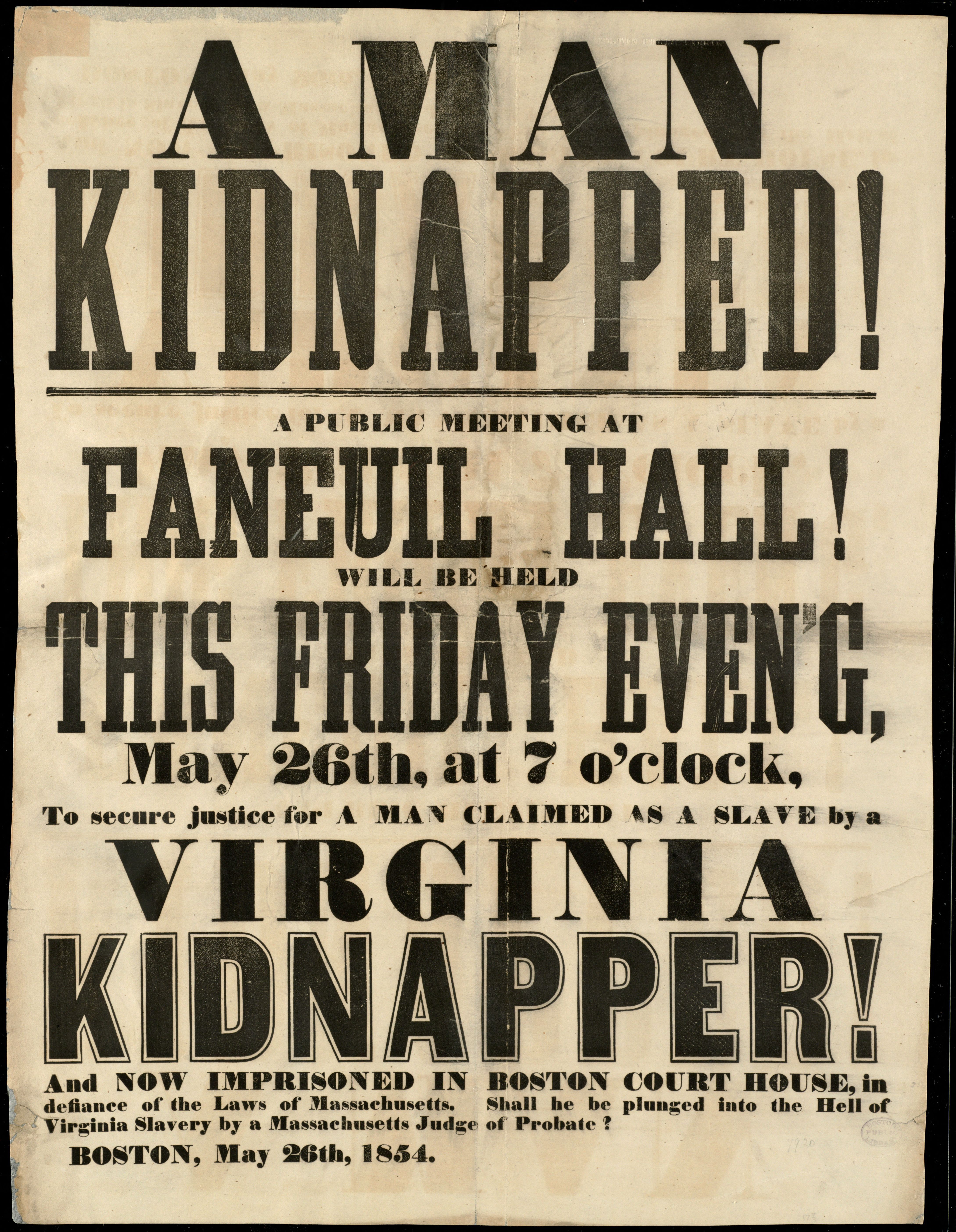

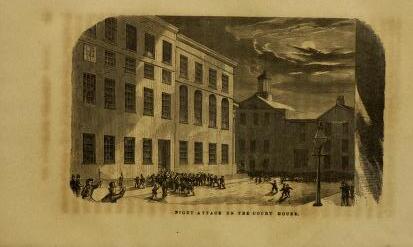

Images: "A man kidnapped!," Ephemera (Boston: s.n., 1854), Digital Commonwealth, accessed September, 2020, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/70796c995; Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 42-43.

[7] James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 120.

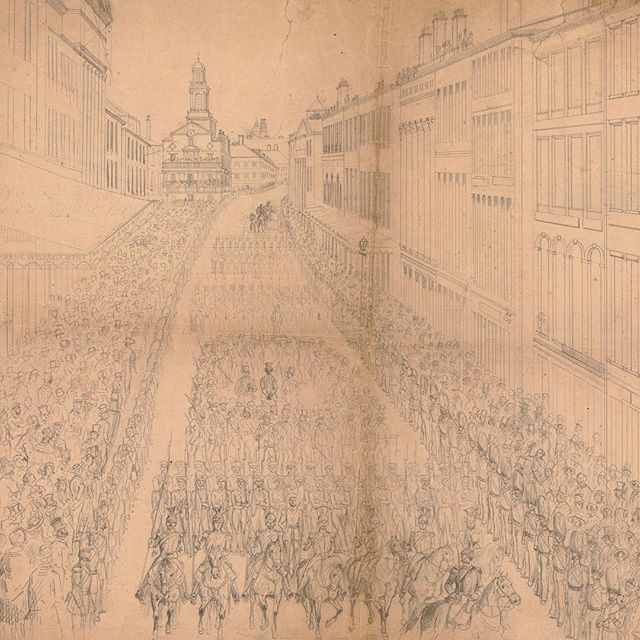

Image: "Rendition of Anthony Burns," sketch by George DuBois, 1854, American Antiquarian Society.

[8] McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 189.

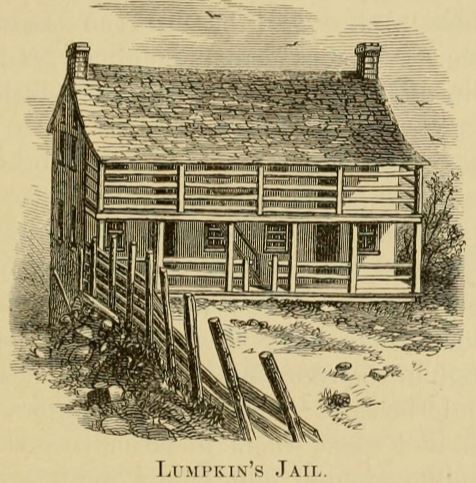

Image: Charles H. Corey, "A history of the Richmond Theological Seminary : with reminiscences of thirty years' work among the coloured people of the South," (Richmond, Va.: J.W. Randolph Company, 1895), Princeton Theological Seminary Library, 47, https://archive.org/details/historyofrichmon00core/page/46/mode/2up?q=lumpkin.

[9] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 202.

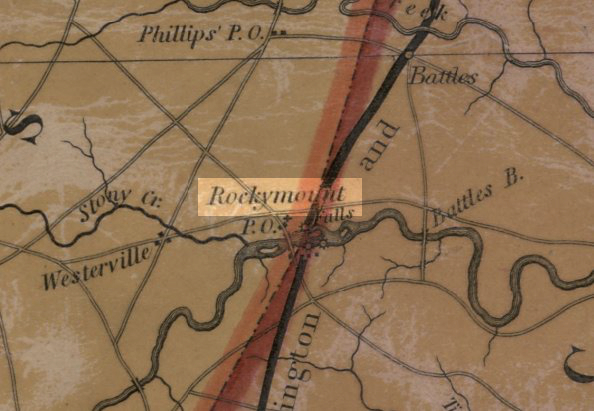

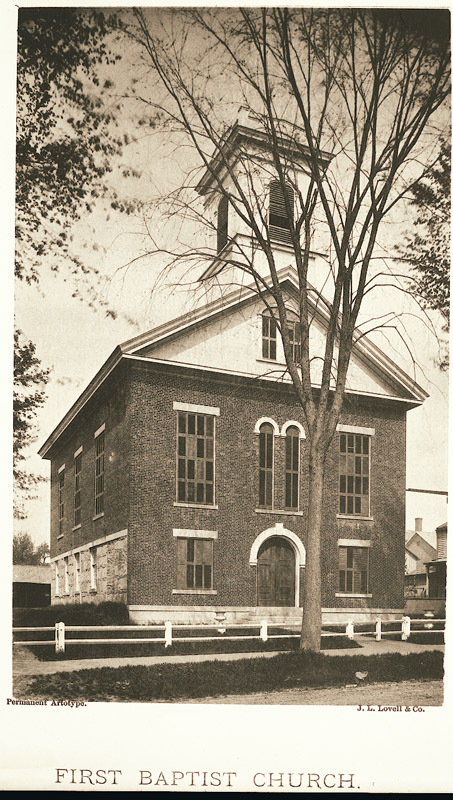

Image: W. Williams, A new map of the state of North Carolina: constructed from actual surveys, authentic public documents and private contributions (Philadelphia: S.N, 1854), Map, accessed September, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/2010587011/; John L. Lovell, “First Baptist Church in Amherst,” Digital Amherst, accessed September, 2020, https://www.digitalamherst.org/items/show/478.

[10] Albert J. Von Frank, The Trials of Anthony Burns (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 290.

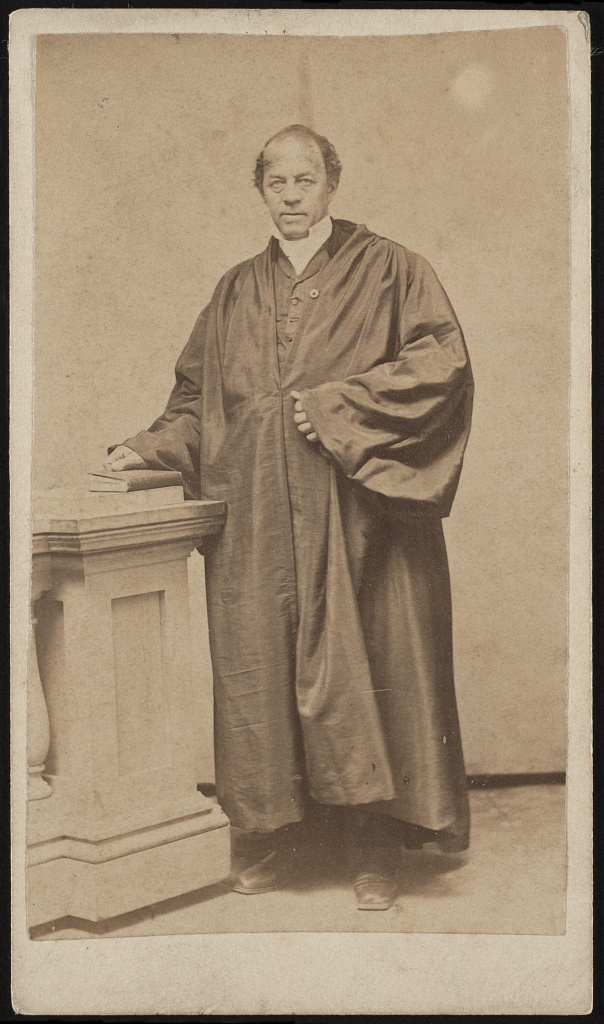

Images: G.H. Loomis, Reverend Leonard Grimes, abolitionist, conductor on the Underground Railroad, and first pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church "The Fugitives Church", Boston / G.H. Loomis, cartes de visite, 7 Tremont Row, Boston, 1860. Photograph, accessed September, 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017660624/; "Barnum's City Hotel, Monument Square, Baltimore," 1858?-1890?, Robert N. Dennis collection of stereoscopic views, New York Public Library, accessed September, 2020.

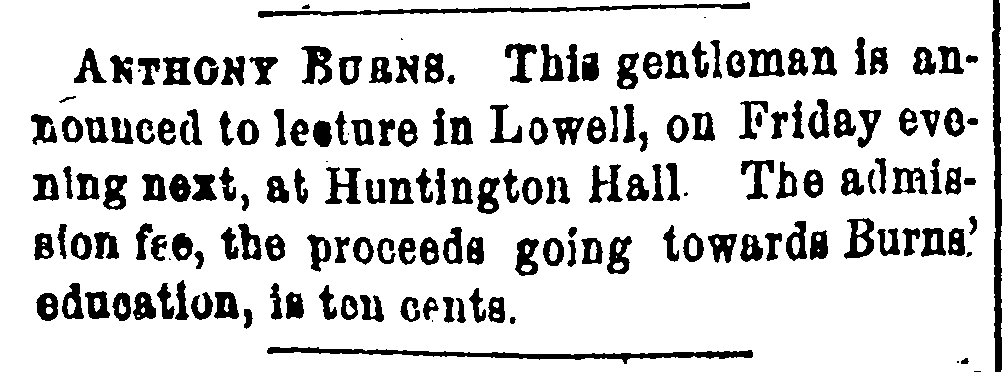

[11] “Anthony Burns Festival,” Boston Herald, March 8, 1855, 2.

Image: "Tremont Temple," The Boston Directory, (Boston: Sampson & Murdock Company, 1851, 68, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015066720791&view=1up&seq=382; "Anthony Burns," Boston Herald, April 20, 1855, Genealogy Bank.

[12] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 216.

[13] “A Fugitive Slave from a Virginia Church,” Buffalo Morning Express, February 13, 1856, 2.

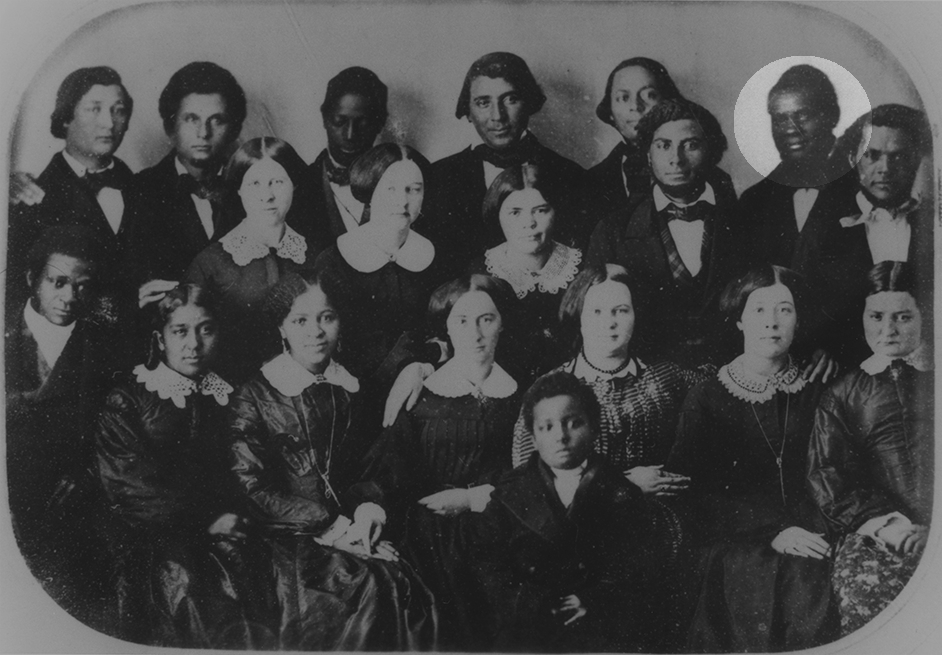

Image: “Preparatory Department Class, 1855,” The Oberlin Sanctuary Project, accessed September, 2020, https://sanctuary.oberlincollegelibrary.org/items/show/16.

[14] Stevens, Anthony Burns: A History, 280.

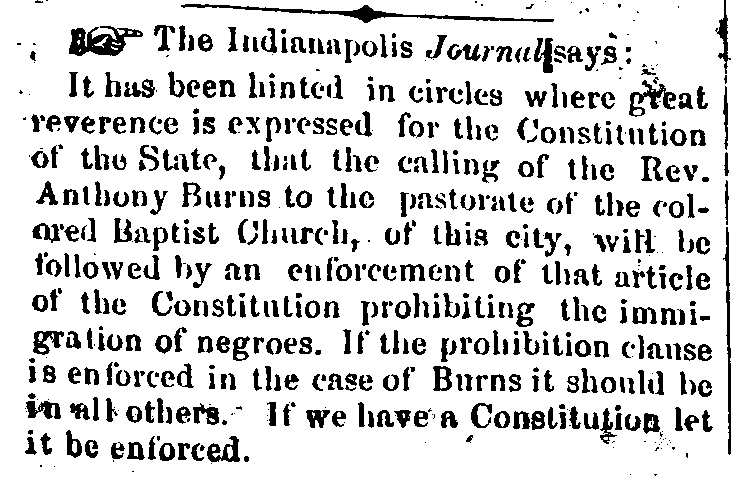

[15] Evansville Journal, August 6, 1859, 3.

Image: Evansville Journal, August 6, 1859, 3.

[16] Robert Samuel Fletcher, A history of Oberlin College from its Foundation Through the Civil War (Ohio: Oberlin College, 1943), 535. Archive.org, https://archive.org/details/historyofoberlin02flet/page/n51/mode/2up?q=anthony+burns

Image: Zion Baptist Church St. Catharines Ontario, St. Catharines Museum & Welland Canals Centre.

[17] Von Frank, The Trials of Anthony Burns, 305.

[18] “Anthony Burns,” Congregationalist, May 2, 1862, 2.

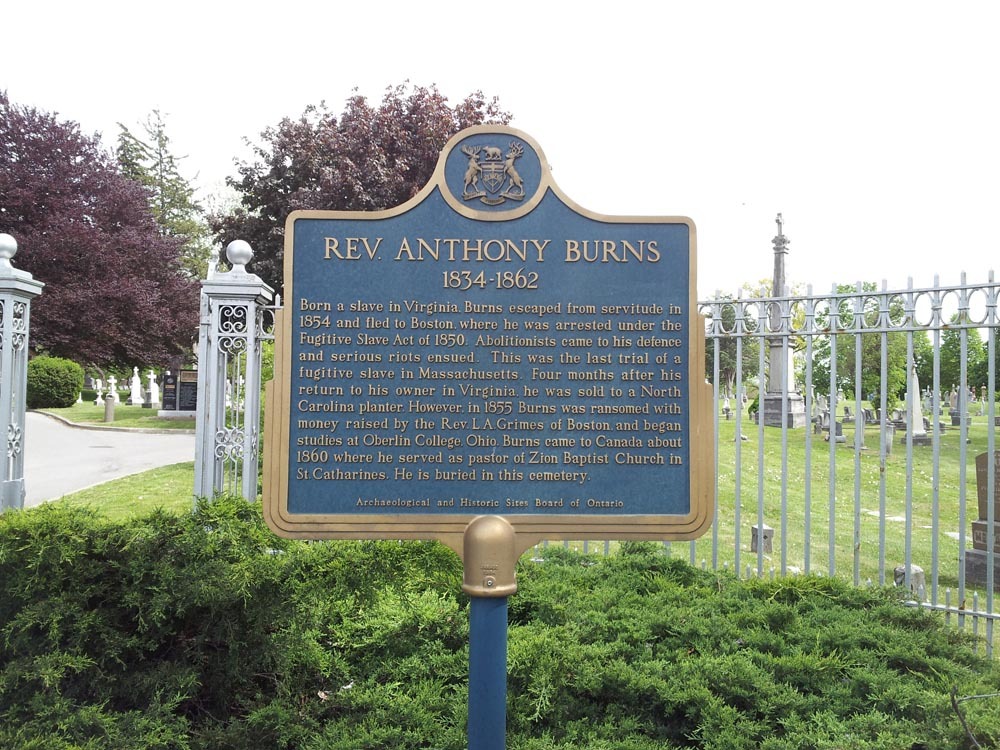

Image: Anthony Burns Grave Site Plaque Photograph, "Niagara's Freedom Trail Sites and Exhibits of the Underground Railroad," Tour St. Catharines, accessed September 2020, http://www.tourstcatharines.com/freedom-trail.shtml.

[19] Fred Landon, “Anthony Burns in Canada” (Columbia University Libraries, 2016), 6. Archive.org https://archive.org/details/anthonyburnsinca00land/page/n5/mode/2up

[20] Michael Valpy, “New Stone Marks Grave of Famous Slave and Pastor,” The Globe and Mail, September 18, 2000.